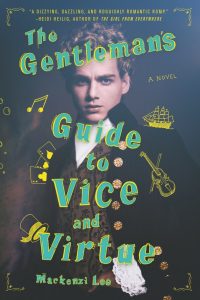

The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue by Mackenzi Lee

Scholars Joe Drury and Danielle Bobker discuss how a recent novel — The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue by Mackenzi Lee — evokes an “engagingly louche” eighteenth century for young adult readers.

Joe Drury: I’m not a great reader of historical fiction nor of YA fiction, so I felt some trepidation accepting your invitation to co-write a review of The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue. But the title and the blurb were just too delicious to resist: the protagonist and narrator, Henry “Monty” Montague, Viscount of Disley (why “of” I’m not sure), is the troubled son of an earl recently expelled from Eton and is now setting off on his Grand Tour with his friend Percy and sister Felicity, eager to indulge his “roguish passions” for gambling, late-night drinking, and philandering with both women and men.

Danielle Bobker: These premises are pretty compelling, I agree. As is Monty himself, right from the start. He’s on the top of my list of the book’s virtues. I did some googling and it turns out this is Mackenzi Lee’s second novel. Her first book, This Monstrous Thing, a steampunk retelling of Frankenstein, won her a lot of fans. Monty’s voice makes it easy to see why she’s been so successful with YA readers.

Joe: Yes, he’s engagingly louche, isn’t he? One part witty Restoration libertine and one part James Boswell of the journals. I was interested to see that Lee cites Boswell’s journals as an influence in a note at the end and, as a Boswell fanboy, I couldn’t help but enjoy the moment when his travelling effects showed up in the second half of the novel.

Danielle: At the same time, Monty’s campiness belongs very much to our own moment: I mean in his attitude as much as his language. For instance, when he watches his best friend stretch himself in bed in the opening pages: “Percy’s showy about so few things, but he’s a damned opera in the mornings.” Or, when the two of them are actually at an opera house half way through and Percy needs help but Monty is stunned: “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. I’m fishing bare-handed in my stream of consciousness for some way to take charge of this situation and be what he needs, and I’m coming up empty.”

The style of Monty’s wanting is not that of any seventeenth- or eighteenth-century rake that I know. He’s more in the mold of the eminently likeable, and eminently marketable, Hollywood romcom rake: Hugh Grant as Daniel Cleaver in Bridget Jones’ Diary. Or whoever the genderqueer boycrush of the hour is (I wish I knew).

On second thought, Monty’s really more like a typical romcom heroine. He loves Percy right from the beginning and waits in agony for signs that the feeling is mutual.

Joe: The fresh diction and familiar teen angst are great, I agree—and essential to Lee’s whole project of inviting young readers to imagine their way into the lives of the eighteenth-century elite. Interestingly there are good eighteenth-century literary precedents for this kind of approach. For instance, as many critics have pointed out, Ann Radcliffe’s novels are set in late-medieval continental Europe, but feature heroines with the values and sensibility of eighteenth-century English women. The historical dissonance between characters and the world through which they move is part of the fun in a Gentleman’s Guide too.

Danielle: Pointing to Radcliffe is especially apt—because when Monty, Percy, and Felicity find themselves in Venice, this travelogue / picaresque / coming of age story becomes a Gothic novel too.

Lately I find myself wondering about the ongoing appeal of the eighteenth century, both to academics and in the popular imagination. Seeing it through Lee’s eyes reminded me that at least one answer lies in the variety of interrelated escape fantasies that the period so readily supports. The fantasy of adventure, of novelty and discovery, definitely. But also the fantasy of total entitlement encapsulated in the figure of the irresistible young rake.

I like how Lee’s all-you-can-eat approach to eighteenth-century literary genres seems to amplify the energy and rashness of adolescence that the novel captures so well in other respects too. (Even if adolescence wasn’t really invented until the nineteenth century.)

And Lee gives us a nice point of reference for making sense of the novel’s generic wildness in Monty’s sister Felicity: Felicity initially appears to be to a female Quixote, but in fact she’s just put the covers of romance novels over the many other books, including medical treatises, that she really wants to read.

Joe: Yes, that bit was great. But there are other kinds of anachronism I found more jarring, only because they seemed unintended. The novel sometimes seems to be set in the early 1720s, or some point during the Regency in France. But other details—such as the reflections on the slave trade and the abolition movement—imply a much later setting. I found the descriptions of eighteenth-century fashion, carriages, and clothing delightfully vivid, but the portrayal of eighteenth-century institutions rather sketchier: Felicity appears to be on her way to some kind of late nineteenth-century European “finishing school,” while Monty is able to walk into the branch of a “French partner institution to the Bank of England” in Marseilles, though he does at least flirt with a male bank clerk to get his cash rather than use an ATM machine.

Danielle: And other things point back several centuries: the alchemy, for instance, which is especially focused around a mysterious ebony box that Monty steals from a duke’s chambers at Versailles, and the notion that people having epileptic seizures have been possessed by the devil.

Joe: Yes, although Lee would probably argue that many of those kinds of “pre-modern” or “superstitious” beliefs would have persisted into the supposedly enlightened eighteenth century. We have never been modern and all that.

And I wonder about Felicity as a character as well. She seems to be symptomatic of an annoying school of thought that assumes that for a work of art to be feminist, it has to depict “powerful,” ultra-capable women doing kick-ass things like Wonder Woman or Angelina Jolie in Mr. and Mrs. Smith, whereas I’m always trying to convince my students that a work of art can be just as, if not more, effective as feminist critique by representing women who are completely deprived of power and the capacity to act because of their circumstances and the society in which they live. Think of Clarissa or Calista or, even a character from a comic novel like Marianne Dashwood. In these stories, patriarchy isn’t so easy to overcome as it is for lucky Felicity. I’ve nothing against kick-ass women (and there are plenty of great ones in eighteenth-century literature, of course), but I felt Lee missed an opportunity with Felicity to give her readers a richer, darker, less comfortable view of what it would have been like to be a woman in eighteenth-century Europe.

Danielle: I see what you mean about Felicity. She is a composite ideal of Lee’s liberal feminist femininity: intellectually autonomous; literary; career-minded; not particularly invested in male sexual approval yet also attractive—above all, highly competent. The character of Percy, a stoic and unassuming person of color, is burdened with blandness in the same way.

Joe: Yes, it is just as easy for Percy to move through this world, even though he is an epileptic of mixed race who is in love with a man. People notice that he is not white and he and Monty have the occasional discussion about the difficulties of the closet. But these difficulties never become more than just opportunities for the expression of a rather pious liberalism. Why not show us what it would have been like to be the victim of homophobia or racism in eighteenth-century Europe rather than just have people talk about it?

Danielle: Although Lee plays with lots of genres, her attachment to the moral promise of sentimental fiction is quite rigid, especially to its central promise to punish or reform vice and reward virtue. Maybe this is the kind of reassuring moral universe that Lee believes YA readers prefer? (My six-year old children certainly do.) But the title makes it sound like vice and virtue will be embraced equally—like in Casanova’s autobiography or Dangerous Liaisons. It’s false advertising.

Joe: Yes, totally. There is, alas, far more virtue than vice in this book.

Danielle: And, ironically, by presenting Felicity and Percy as morally flawless, Lee actually recapitulates Monty’s basic socioeconomic, racial, and patriarchal privilege: only the rich white guy has the right to be complicated.

Hearing from Felicity and Percy as narrators would have gone a long way to redressing this imbalance, I think. I don’t necessarily agree that their suffering more would have made them better vehicles of critique. But I do think that Lee could have shown that, like Monty, but for good reasons often much more than him, these characters also have to learn to navigate, skirt around, or, occasionally, go head to head with dominant power structures. Even Pamela Andrews has edges.

Joe: Fair enough, although just as he is the only one who is allowed to be complicated and flawed, I’d argue that Monty is also the only character who really suffers and the only one as a result who undergoes any kind of moral development. The ending reminded me a bit of Game of Thrones, where unsympathetic characters like Jaime and Theon only begin to acquire moral feeling and complexity once they’ve been disabled or mutilated in some way. But George R. R. Martin and co also show us what it feels like to be a dwarf or a bastard or a woman in Westeros. In this novel, it feels as if the woman and the black man are just there to be props for the white male protagonist’s liberal moral awakening. Why couldn’t Felicity actually behave like one of Haywood’s heroines instead of just pretending to read about them? My understanding is that YA fiction often goes to these darker places these days—I’ve seen The Hunger Games!—so I don’t think it’s necessarily a question of audience. And as you say, eighteenth-century literature often has a harder, Hobbesian edge so it’s not a question of period authenticity either.

Danielle: Yes, it’s disappointing that, rather than using the past as a pretext to explore ongoing ethical dilemmas, Lee simply encases her fixed contemporary moralism into this vaguely historical package. So, ultimately, I guess we suggest enjoying The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue, then chasing it with something a little stronger.

Further reading recommended by Joe and Danielle:

Literature of libertinism

- John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, Poems

- Eliza Haywood, Love in Excess, Fantomina, The Masqueraders, Anti-Pamela, The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless

- Casanova, Memoirs

- James Boswell, The London Journal, The Grand Tour

- John Cleland, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

- Choderlos de Laclos, Dangerous Liaisons

- George Etherege, The Man of Mode

- Aphra Behn, The Rover

- William Wycherley, The Country Wife

- The Libertine Reader: Eroticism and Enlightenment in Eighteenth-Century France

- When Flesh Becomes Word: An Anthology of Early Eighteenth-Century Libertine Literature

Other literature of the period

- Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho, The Italian, The Romance of the Forest

- Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote

- Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility

- Samuel Richardson, Pamela

Relevant academic studies

- George Haggerty, Men in Love: Masculinity and Sexuality in the Eighteenth Century

- Susan Lanser, The Sexuality of History

- Alan Bray, The Friend

- Randolph Trumbach, Sex and the Gender Revolution

- Rictor Norton, Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England, 1700-1830

- Karen Harvey, Reading Sex in the Eighteenth Century: Bodies and Gender in English Erotic Culture