The digital scenery for the staged reading of The Mysterious Mother was designed by Alice Trent and projected onto the concrete walls of auditorium in the Yale Center for British Art.

Author Archives: Jessica Richard

Jessica Richard is an Associate Professor of English at Wake Forest University where she specializes in eighteenth-century British fiction. She is Co-Editor of 18th-Century Common.

The Mysterious Mother Mini-Conference: Session I

Session I of The Mysterious Monther mini-conference on May 3, 2018, held at the Yale Center for British Art, was titled “Reading The Mysterious Mother” and was chaired by Jill Campbell, Professor of English, Yale University. Session I can be viewed in its entirety below. The session featured the following papers:

- Dale Townshend, Professor of Gothic Literature, Manchester University. “The Mystery of The Mysterious Mother: Textual Lives and Afterlives”

- Matthew Reeve, Associate Professor, Art History, Queens University. “The Mysterious Mother and Crypto-Catholicism in the Circle of Horace Walpole”

- Nicole Garret, Lecturer, Department of English, SUNY Stony Brook. “Mis-reading in The Mysterious Mother“

- Cheryl Nixon, Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Massachusetts, Boston. “The Mysterious Orphan: Dramatizing the Betrayal of the Child”

- Nicole Wright, Assistant Professor of English, University of Colorado, Boulder. “‘Kindest Laws’: Intimate Ajudication in The Mysterious Mother“

The Mysterious Mother Mini-Conference: Session II

Session II of The Mysterious Monther mini-conference on May 3, 2018, held at the Yale Center for British Art, was titled “Staging The Mysterious Mother” and was chaired by Misty Anderson, James R. Cox Professor of English at the University of Tennessee. Session II can be viewed in its entirety below. The session featured the following papers:

- Marcie Frank, Professor of English, Concordia University. “Wilful Walpole: Performing Publication and The Mysterious Mother“

- Jean Marsden, Professor of English, University of Connecticut. “Family Dramas: The Mysterious Mother and the Eighteenth-Century Incest Play”

- Al Coppola, Associate Professor of English, John Jay College, CUNY. “Spectacles of Science and Superstition”

- Judith Hawley, Professor of English, Royal Holloway, University of London. “‘the beautiful negilence of a gentleman’: Horace Walpole and Amateur Theatricals

- David Worrall, Professor Emeritus, Nottingham Trent University. “‘I beg you would keep it under lock and key’: The Mystery of the 1821 Mysterious Mother Performances”

Statement of Support for the National Endowment for the Humanities

The 18th-Century Common was developed with substantial support from the Wake Forest University Humanities Institute, which itself was founded with generous support from an National Endowment for the Humanities Challenge Grant. We are grateful that NEH funding has enabled an international array of scholars writing for The 18th-Century Common to share research with nonacademic enthusiasts of eighteenth-century studies.

The 18th-Century Common was developed with substantial support from the Wake Forest University Humanities Institute, which itself was founded with generous support from an National Endowment for the Humanities Challenge Grant. We are grateful that NEH funding has enabled an international array of scholars writing for The 18th-Century Common to share research with nonacademic enthusiasts of eighteenth-century studies.

Read the Wake Forest University Humanities Institute’s Statement of Support for the NEH.

We Want You to Get Involved with The 18th-Century Common

The Coffeehous Mob, frontispiece to Ned Ward’s Vulgus Britannicus (1710).

We’re excited to announce new ways to get involved with The 18th-Century Common, the public humanities website for nonacademic, nonstudent enthusiasts of 18th-century studies.

There are two kinds of posts on The 18th-Century Common: Features posts and Gazette posts. In Features posts, scholars describe their own research, whether published or in progress (Read Rebekah Mitsein’s account of how her Features post on The 18th-Century Common helped her on the academic job market). Features posts can be on existing topics gathered in thematic Collections on The 18th-Century Common, or on new topics. We also seek new Collection Curators, who draw on their existing scholarly networks to solicit Features or Gazette contributions from scholars on a specific topic of interest to the Collection Curator.

In Gazette posts, scholars or students situate recent publications by others—whether in academic or popular media—in scholarly contexts. Gazette posts show how a recent publication participates in the conversations of eighteenth-century scholarship (see, for example, Cassandra Nelson’s Gazette post on a BBC article by Adam Gopnik about the “Mechanical Turk”). We’re using the content curation plugin PressForward to generate topics for Gazette posts. PressForward enables 18th-century enthusiasts (nonacademic or academic!) to nominate content from around the web for inclusion in 18th-Century Common Gazette posts by posting a link on Twitter with the hashtag #18common. We also use PressForward to collect abstracts of new journal publications for possible Gazette posts. We encourage faculty to incorporate the writing of Gazette posts into their graduate seminars or advanced undergraduate classes. Writing a Gazette post gives students practice situating work in scholarly contexts as well as practice communicating ideas clearly to an intelligent, nonacademic readership. Gazette Contributors will have access to a range of possible material for Gazette posts gathered by PressForward; a Gazette Contributor may choose the topic of a post from this material or from other publications.

Read more about these ways of getting involved in The 18th-Century Common: our Get Involved page includes tutorials on nominating content with the Twitter hashtag #18common as well as on using PressForward to create Gazette posts. Contact the editors at [email protected] with questions, proposals for Features or Gazette posts, interest in serving as (or assigning your students to serve as) Gazette Contributors, or interest in becoming a Collection Curator.

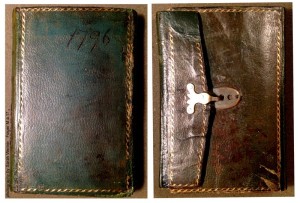

Interiority and Jane Porter’s Pocket Diary

Cover of Jane Porter’s pocket diary. Photograph by Sarah Werner. Folger M.a.17

Julie Park, Assistant Professor of English at Vassar College, describes her fascinating recent research into the “written documents of daily life from real eighteenth-century lives” at the Folger Shakespeare Library:

It’s been a critical commonplace after Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel to view the novel as the first literary form to represent psychological individuality in the context of everyday life. My research, however, examines how the spaces and objects of daily life in eighteenth-century England worked as vehicles of interior experiences in their own right. Working from this angle might change our conceptions of the novel, not only its historical relationship to how selfhood is defined, but also its relationship to the material culture of the greater society around it.

By using my Folger long-term fellowship to look at written documents of daily life from real eighteenth-century lives, I thought I might complicate claims about the early novel’s method of representing interior or psychological experience through diurnal structures.1 One line of my exploration was how a form of portable interiority surfaced in the small books that were designed for carrying in one’s pocket. The novel itself, in its eighteenth-century print manifestation, was pocket-sized, conveying not only its affordability and portability, but also its ability to be held in the hand and worn against the body. Just as the novel conveyed its own interior worlds to readers, the experience of reading the physical book created an interior world between the novel and its reader, even when carried into exterior settings, from pleasure gardens to carriages for travel.2

Among the holdings of eighteenth-century pocket-sized books I found at the Folger is The Ladies Memorandum Book, for the Year 1796 (M.a.17), a green leather book with gold tooling around its edges. At 12×7.5 cm, it can easily be held in the palm of one’s hand. Its fore-edge is covered by a flap that extends from the front cover and is attached to the back by a gold clasp. Flipped to its back, with its diagonal seamed flap, the book resembles a modern day envelope. Yet its sides are left open, and there is a thickness to its body created by the stack of pages sewn into its spine. Further examination of the book will reveal it indeed functions as much of an envelope and a pocket as a book.

Read the rest of Julie Park’s account of this object at the Folger’s blog.

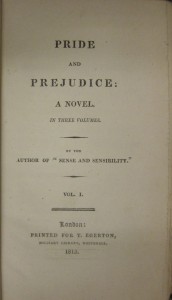

Pride & Prejudice at 200

Jane Austen scholars are currently marking the 200th anniversary of the publication of Pride and Prejudice. Here are just a few of the many commemorations from around the web:

Megan Mulder, Special Collections Librarian at Z. Smith Reynolds Library, Wake Forest University, describes the novel’s long path to publication, its reception by critics, and the larger context of Austen’s publishing career in a post for the Z. Smith Reynolds Library Special Collections Blog. Her informative post includes several photographs of Wake Forest’s first editions of Austen’s work, as well as those of her predecessor Frances Burney.

Devoney Looser, in an essay for the Los Angeles Review of Books, reviews two recent scholarly books that attempt to make sense of Austen’s enduring appeal:

The permeable boundaries between the popular and sometimes absurd Austen and the scholarly Austen surely matter in ways that will be long in unraveling. Recent Austen scholarship has capitalized on this high-low traffic, mirroring the marketing of “I [Heart] Darcy” bumper stickers more than we might like to admit — and I don’t exempt myself from the charge of opportunism. I am an English professor who has the good fortune to teach Jane Austen by day. By night, I skate on the local roller derby team as my alter ego, Stone Cold Jane Austen. As a result, I regularly field such farcical questions as “What would Jane Austen think of tattoos?” and, from my son, “Mommy, who is Jane Austen? Are you Jane Austen?” So I do not speak here from on high. The shrines to Jane Austen in my life involve sweat-stained wrist guards, not 19th-century editions of her works. But even I find myself asking on occasion, “What is the point of our sifting through and documenting all of today’s Austen-infused dreck?” It is especially heartening, then, to find emerging work on Austen and popular culture that moves beyond recounting how she has been mashed up with zombies, vampires, or porn. The best new work asks not only the multivalent, unanswerable question, “Why Austen? Why Now?” It also carefully charts “How did we get here?”

Both Claudia L. Johnson’s Jane Austen’s Cults and Cultures and Janine Barchas’s Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity are exemplars of this more sophisticated work on Austen and popular culture. Johnson’s book makes sense, directly and indirectly, of the factual-fiction impulse behind novels like Pattillo’s Jane Austen Ruined My Life, telling the fascinating story of how the mystique of Austen was gradually created, maintained, and spun out in unpredictable ways in the years after her death in 1817. Johnson unearths both the many-sided truths and the wide-ranging implications of our false fantasies of Austen, drawing conclusions from evidence ranging from portraits and memorials to fairy tales and relics. By contrast, Barchas makes a compelling case for our acknowledging some of the real-life 18th- and 19th-century people who may stand behind Austen’s fictional characters, in order to reveal long occluded ways of seeing Austen’s relationship with history and celebrity culture.

Elsewhere in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Susan Greenfield and Audrey Bilger offer an engaging account of the fate of Pride and Prejudice over the past 200 years, and Ted Scheinman reviews a new biography of Austen.

In 2006 Linda V. Troost published an analysis of three film interpretations of Elizabeth’s visit to Pemberley in Eighteenth-Century Fiction. You can read the entire article without charge here.

Want to celebrate? Pride & Prejudice 200 collects listings of commemorative events worldwide.

Daniel Defoe Around the Web

Twelve Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by Carington Bowles, 1724-1793, British. Yale Center for British Art, Yale University Art Gallery Collection.

Here are some recent internet gleanings for enthusiasts of Daniel Defoe to explore:

- Stephen H. Gregg posts monthly on his Daniel Defoe Blog; most recently he wrote about what readers should call the character commonly known as “Roxana.”

- This Eighteenth-Century Fiction Tumblr post collected recent essays published in the journal’s pages on Robinson Crusoe.

- The online journal Digital Defoe is freely accessible to all readers. The most recent issue includes essays on marriage equality in Roxana, optics in Robinson Crusoe, and more.

- You can browse the Daniel Defoe Collection of Indiana University’s Lilly Library to see high-resolution images of a range of Defoe texts, including his political pamphlets, children’s editions of Robinson Crusoe, and his treatises on trade and finance.

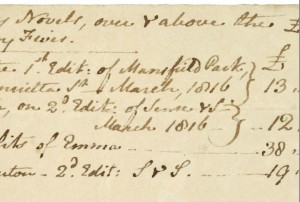

Happy (Recent) Birthday, Jane Austen!

Detail of Jane Austen’s autograph note concerning the “Profits of my Novels, over and above the £600 in the Navy Fives” ca. March 1817. The Morgan Library and Museum.

Jane Austen was born on December 16, 1775, and we want to highlight a few items around the web marking the occasion:

- At Ms. Magazine Audrey Bilger (Professor of Literature, Claremont McKenna College) notes that on the occasion of Austen’s birth “Most likely much of the attention will focus on Austen as a writer of romances. Each of the novels concludes in marriage, after all, and the marriage of Elizabeth to Mr. Darcy is a particularly happy ending. We should also pay tribute, however, to Austen’s early adoption of feminist ideals and her insistence that women’s voices and experiences be taken seriously.” Read her account of “Five Feminist Footnotes” to Jane Austen’s work here.

- At the British Newspaper Archive, Ed King highlights the advertisements and newspaper notices for some first editions of Austen’s novels in the early nineteenth century. The post includes images of the original newspapers (which are normally available only to subscribers).

- The Morgan Library maintains an online version of its 2010 exhibit “A Woman’s Wit: Jane Austen’s Life and Legacy” which includes images of Austen manuscripts owned by the Morgan, video of luminaries such as Cornel West, Fran Leibowitz, Colm Tóibín, and others describing what Austen means to them, and more.

Dogs of the 18th Century

Brown and White Norfolk or Water Spaniel Date, 1778. By George Stubbs (1724-1806, British). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Scholars date both the beginnings of modern pet-keeping and modern discourses of animal rights to the eighteenth century. Here is just a small sampling of recent scholarly work on dogs in eighteenth-century life.

Laura Brown‘s book Homeless Dogs and Melancholy Apes (Cornell University Press, 2010) shows

how the literary works of the eighteenth century use animal-kind to bring abstract philosophical, ontological, and metaphysical questions into the realm of everyday experience, affording a uniquely flexible perspective on difference, hierarchy, intimacy, diversity, and transcendence. Writers of this first age of the rise of the animal in the modern literary imagination used their nonhuman characters—from the lapdogs of Alexander Pope and his contemporaries to the ill-mannered monkey of Frances Burney’s Evelina or the ape-like Yahoos of Jonathan Swift—to explore questions of human identity and self-definition, human love and the experience of intimacy, and human diversity and the boundaries of convention.

Lynn Festa‘s article on the English Dog Tax debate of 1796 was published in the journal Eighteenth-Century Life in 2009. The abstract describes it thus (full text of the essay is available here):

Drawing on Parliamentary debates, print polemics, and satirical prints, this essay traces the rhetorical erosion of seemingly categorical distinctions between human and animal, animate and inanimate, person and thing, in the controversy that arose around the 1796 imposition of a tax on dogs. The passage of this seemingly slight piece of legislation created impassioned debates about the nature and welfare of animals, about the rights of individuals to possess or keep property, and about the way the kinship felt for animals tampers with the seemingly self-evident borders of kind. At a moment in which sentimental humanitarian concern with the rights and interests of animals had reached new heights, the taxation of dogs seemed to reclassify the animal as a thing and to draw into question the relation between humans and their ostensible best friends. Although proponents of the bill endeavor to proceed as if dogs can be considered on the same terms as other kinds of taxable luxuries (devouring resources that might better be devoted to humans), opponents of the tax focus on the bonds of mutual dependency and reciprocal obligation that tie humans and animals together, arguing that the right to keep a beloved entity such as a dog expresses a distinctively human need to keep something beyond mere, bare, necessity. Inasmuch as humanity is expressed and inheres in the relation people take to other creatures, the seeming superfluity of the dog embodies the essence of what allows, or enables, people to act as humans.

Chi-ming Yang, in “Culture in Miniature: Toy Dogs and Object Life” in Eighteenth-Century Fiction examines porcelain dog figurines (particularly of the pug and King Charles spaniel, breeds imported from Asia and domesticated in England) produced in China and sold in England in the eighteenth century. She argues:

The toy dog, a small but far from trivial commodity, mediated relations of racial, sexual, and species difference and helped establish a luxury market for the pet as a racialized fetish object that continues to this day.

The Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, published by the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, produced a Special Issue on “Animals in the Eighteenth Century” in December 2010. While the full contents are only available to members and institutional subscribers, anyone can read abstracts of the articles at the link above.

Bernadette Paton of the Oxford English Dictionary charts the changing uses of dog-related vocabulary over time and notes that the eighteenth-century is an important turning point:

Until the eighteenth century small dogs kept as pets were regarded with some disdain (hence the negative connotations of lap-dog) but they enjoyed luxuries their outdoor counterparts could only dream of. But from the mid-1700s compounds attesting to the dog as a favoured and nurtured pet begin to appear, and they multiply and flourish throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. They include comforts like dog baskets (earliest in 1768 Catal. Household Furniture, ‘A dog-basket and cushion’), dog biscuits (specialized dog treats, from 1823), dog food, dog doctors (first recorded in 1771 Tobias Smollett’s novel Humphry Clinker, ‘A famous dog-doctor was sent for’), dog hospitals (from 1829), and dog soap (first use 1869). The first reference to the dog as ‘man’s best friend’ appears in 1841, at a time when dogs began to be sentimentalized, and to be seen as having, if not souls, then at least personalities and feelings (perhaps because the industrialized city no longer needed them as outdoor working or guard animals, while the rabies vaccination developed in the 1880s reduced the threat they posed).

Two articles in the Colonial Williamsburg Journal describe the dog’s life in the eighteenth century for a non-academic readership: “The Eighteenth Century Goes to the Dogs” (including a quiz matching eighteenth-century dogs to their famous owners) and “Personable Pooches.”

And someone has collected a vast array of eighteenth-century portraits of pets (many of them dogs) and their owners on Pinterest.