In some senses, English subjects have always cared about whom their queens, kings, princes, and princesses chose to marry, and speculations about marriage agreements and relationships have long preoccupied courtiers, members of parliament, and the wider public. Despite popular anxieties about her authority and the perpetuation of the succession, for instance, Elizabeth I chose not to marry, although she engaged in delicate courtship rituals and marriage negotiations as tools of foreign and domestic policy. Charles I, when still Prince of Wales, undertook a disastrous trip to Madrid to negotiate an ultimately unsuccessful (and unpopular) match with the Infanta Maria, daughter of Philip III of Spain. Instead he wed the French Catholic Henrietta Maria by proxy in 1625, and despite their union getting off to a rocky start, by the late 1630s Parliamentarian critics satirized the king as an uxurious husband who put the interests of his papist wife above the welfare of the kingdom. During the Succession Crisis and debates about Exclusion in the later 1670s and early 1680s, some Whig-leaning writers insisted that Charles II had secretly married the Duke of Monmouth’s mother, Lucy Walter, in 1649, thereby establishing the Protestant Monmouth as the legitimate heir in place of the king’s Catholic brother James, Duke of York. Others urged Charles to divorce his Catholic, childless queen, Henrietta Maria, and remarry. Indeed, any list of royal matrimonial escapades must mention George I’s ill-fated marriage to Sophia Dorothea, whom he locked away in a castle in Ahlden in 1694 after he discovered she had been unfaithful (possibly also ordering her lover to be murdered and tossed into the Leine river). And who can forget George IV’s secret marriage to the widowed Catholic Maria Fitzherbert in 1785 when he was still Prince of Wales, or his public estrangement from Caroline of Ansbach and his infamous (and unsuccessful) attempt to divorce her amid widespread criticism and out-of-doors demonstrations of loyalty for the wronged queen? [1]

But when we search for historical antecedents to the rise of the “royal” wedding as a mediated cultural phenomenon that disseminates the spectacle of monarchy and the romance of regal conjugality to an increasingly mass audience, we usually look to the nineteenth century, especially the marriage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1840. In the weeks prior to the ceremony, newspapers carried effusive stories about court preparations and the queen’s chosen bridal color—“Lily, or English Pure White,” of entirely British manufacture—which was predicted to become the “prevailing colour of the season.” [2] Victoria’s dress, stitched of Spitalfields silk and Honiton lace, included a long train trimmed with orange blossoms, and journalists reported that the lace alone cost more than £1000. [3] Houses along the queen’s procession route between Buckingham Palace and St. James’s Palace were decorated with flags, banners, and illuminations. Despite the rainy February weather, throngs of anxious spectators lined the city streets or purchased tickets to watch the couple pass from windows, balconies, and the roofs. “Every eye was directed to the state carriage,” one newspaper reported, “and as soon as it was in motion, the sounds of loud huzzas, and the strains of the national anthem rent the air, while on every side the waving of hats and handkerchiefs greeted her Majesty.”[4] Those unable to witness the marriage in person, of course, purchased broadside renderings of the royal couple, delicate engravings of Victoria in her wedding clothes, and panoramas of the marriage procession. [5]

Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange and William Charles Henry Friso Prince of Orange.

I want to suggest, however, that the most promising place to look for the origins of the royal wedding as a celebrated event that also turned the royal family into quasi-celebrities is in the eighteenth century, and specifically the 1730s. This was a moment shaped by the continued maturation of London’s newspaper and periodical press after the expiry of print licensing in 1695, and the emergence of the patriotic opposition to Robert Walpole’s ministry, which overlapped with emerging divisions within the royal household. Although George II is still remembered as a rather frugal but staunchly Protestant ruler, adverse to large crowds and baroque spectacle, the Hanoverian court continued to function as a center of elite cultural life within London. [6] And a brief examination of the printed representations of the weddings of George II’s two eldest children—Princess Anne to William IV, Prince of Orange, in 1734, and Frederick, Prince of Wales, to Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha in 1736—reveals the ways in which the royal nuptials had become a space of popular longing, partisan criticism, commercial celebration, and affective political drama, especially as the events became the focus of new journalistic practices. Newspapers eagerly covered all aspects of each wedding, offering their readers vivid descriptions of the activities and engagements of the betrothed, the decoration of palace buildings and apartments, and the au courant fashions worn by courtiers and royals at each marriage ceremony.

The Prince of Orange was small of stature with a misshapen spine and slumped right shoulder, and when he arrived in England in November of 1733, he immediately contracted a fever, delaying his marriage with Anne until the following spring. London newspapers eagerly reported on William’s recovery, though, and his subsequent travels through Bristol, Bath, Oxford, and Windsor the following February, with some writers intending their glowing coverage of the prince’s popular acclaim as a dig at the king’s seeming inaccessibility and frequent trips to Hanover. Upon his arrival in Bristol, the Daily Journal and the Penny London Post, among other newspapers, reprinted lengthy extracts from a letter detailing the prince’s entry and entertainment in that city of pleasure. Met on the main road into town by two sheriffs in a chariot and six, over eight hundred horsemen, and gentlemen and merchants in private coaches, the procession marched to the common led by the Company of Wool-Combers dressed in white shirts and “Orange-Coloured Wool-Perriwigs.” “The Streets and Houses being so thronged with Spectators,” the correspondent reported, “that the City appeared as one great living Body bespangled with Eyes.” [8]

Anne and William’s wedding was held in March at St. James’s Chapel, which had been richly decorated for the occasion by the celebrated architect and painter William Kent. A contemporary engraving of the ceremony captures the prince and princess with hands clasped in the act of exchanging vows before the Archbishop of Canterbury, while ostentatiously dressed courtiers fill the chapel, gossiping and fanning themselves flirtatiously. [9] The wedding was thoroughly documented in almost every London newspaper, and writers emphasized the size of the crowds at the palace, the rich appearance of the nobility, and the voluntary festivities of London’s citizenry, which included the illumination of the Monument and Ludgate with glass lamps, plentiful bonfires, and fireworks. The Daily Journal published a laboriously detailed narrative of the entire wedding procession to and from the chapel, concluding with a public dinner in the State Ballroom, before the nobility filed through the prince and princess’s bedchamber to view them sitting up in their marriage bed “in rich undress.” The London Evening Post and the Penny London Post offered rambling descriptions of the wedding costumes and other finery observed at court. The bride wore diaphanous “Virgin Robes of Silver Tissue, having a train six Yards long, laced around with a massy Lace, adorn’ed with Fringe and Tassels; on the Sleeves were several Bars of Diamonds of great value; the Habit was likewise enrich’d with several Rows of oriental Pearl.” The women of the beau monde donned “fine laced Heads, dress’d English,” and their dresses featured “treble Ruffles, one tack’d up to their Shifts in quil’d Pleats and two hanging down; the newest fashion’d Silkes were white Paduasoys, with large Flowers of Tulips, Peonies, Emmonies, Carnations, &c. in their proper Colours, some wove in Silk, and some embroidered.” Other papers claimed that the “Embroidery and Beauty” of the princess’s wedding clothes “exceed any thing that has been ever seen here, tho’ all of Manufactures of this Kingdom.” [10] These lengthy and exacting descriptions of fashionable and fine court costume as reproduced in metropolitan newspapers broadcast important political messages. Expensive and newly purchased court attire was used to demonstrate allegiance to the crown and respect for the person of the monarch, while careful accounts of hairstyles, dress cuts, and fabric patterns portrayed the court and royal family as taste leaders who followed fashion trends and encouraged native industry. [11] At the same time, the wedding inspired the production of a whole range of commemorative commercial objects for consumers in Britain and the Netherlands, including medals, highly ornamental engraved paper fans, and enameled porcelain bowls decorated with the portraits of Anne and William, who seem to gaze into each other’s eyes. [12]

Anne and William’s wedding was held in March at St. James’s Chapel, which had been richly decorated for the occasion by the celebrated architect and painter William Kent. A contemporary engraving of the ceremony captures the prince and princess with hands clasped in the act of exchanging vows before the Archbishop of Canterbury, while ostentatiously dressed courtiers fill the chapel, gossiping and fanning themselves flirtatiously. [9] The wedding was thoroughly documented in almost every London newspaper, and writers emphasized the size of the crowds at the palace, the rich appearance of the nobility, and the voluntary festivities of London’s citizenry, which included the illumination of the Monument and Ludgate with glass lamps, plentiful bonfires, and fireworks. The Daily Journal published a laboriously detailed narrative of the entire wedding procession to and from the chapel, concluding with a public dinner in the State Ballroom, before the nobility filed through the prince and princess’s bedchamber to view them sitting up in their marriage bed “in rich undress.” The London Evening Post and the Penny London Post offered rambling descriptions of the wedding costumes and other finery observed at court. The bride wore diaphanous “Virgin Robes of Silver Tissue, having a train six Yards long, laced around with a massy Lace, adorn’ed with Fringe and Tassels; on the Sleeves were several Bars of Diamonds of great value; the Habit was likewise enrich’d with several Rows of oriental Pearl.” The women of the beau monde donned “fine laced Heads, dress’d English,” and their dresses featured “treble Ruffles, one tack’d up to their Shifts in quil’d Pleats and two hanging down; the newest fashion’d Silkes were white Paduasoys, with large Flowers of Tulips, Peonies, Emmonies, Carnations, &c. in their proper Colours, some wove in Silk, and some embroidered.” Other papers claimed that the “Embroidery and Beauty” of the princess’s wedding clothes “exceed any thing that has been ever seen here, tho’ all of Manufactures of this Kingdom.” [10] These lengthy and exacting descriptions of fashionable and fine court costume as reproduced in metropolitan newspapers broadcast important political messages. Expensive and newly purchased court attire was used to demonstrate allegiance to the crown and respect for the person of the monarch, while careful accounts of hairstyles, dress cuts, and fabric patterns portrayed the court and royal family as taste leaders who followed fashion trends and encouraged native industry. [11] At the same time, the wedding inspired the production of a whole range of commemorative commercial objects for consumers in Britain and the Netherlands, including medals, highly ornamental engraved paper fans, and enameled porcelain bowls decorated with the portraits of Anne and William, who seem to gaze into each other’s eyes. [12]

The broad journal coverage of Anne and William’s wedding evinces both desire for accessible royal figures and readers’ fascination with the theatrical spectacle of British court culture. Although newspaper coverage did not spotlight individual personalities or the intimate side of the royal family in the same way that later eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century journalists and periodical authors would, this reportage, nonetheless, opened the royal palace to the public gaze, inviting spectators and entire cities “bespangled with Eyes” to take part in the drama of royal romance.

Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, Princess of Wales

Frederick’s 1736 marriage follows these same journalistic patterns, with newspapers offering glowing coverage of Augusta’s arrival at Greenwich in late April. “Several thousand people” were reported to have flocked to glimpse Britain’s new princess at the Queen’s House—the editor of Read’s Weekly Journal estimated that the crowds numbered no less than 10,000 persons—and Augusta was described as having “very beautiful features, a fine complexion” and “a very Majestick and becoming Air.” The press circulated rumors that the wedding would take place not at the chapel at St. James’s Palace, but at the much larger St. Paul’s Cathedral, which could accommodate additional spectators and would allow a state procession through the City in full regalia and coronation robes. [13] Ultimately, this story proved false, a mere reflection of public desire for access to the pageantry of royal romance that would have represented a far-reaching departure from the precedents governing state marriages. Newspapers printed encomiastic verses about the princess’s august Protestant pedigree, plays were performed in honor of the royal couple, and the wedding gave enterprising churchmen an excuse to publish sermons on virtuous love and conjugal duty. Church bells rang, bonfires were lit, and toasts were given throughout cities and villages in England, Scotland, and Ireland, all of which was reported in the metropolitan press. And again journalists offered tedious descriptions of court dresses, stockings, shoes, jewels, and hairstyles worn for the wedding celebrations, with entire pages dedicated to reproducing the lavish spectacle of the British crown and the beau monde. [14] The bride’s dress and the court costumes of her ladies in attendance were embroidered by a Mrs. Ganderoon, Her Majesty Queen Caroline’s appointed embroideress, requiring “above 120 persons at work in making the rich cloaths.” “There’s the greatest Demand at this Time for Gold and Silver Stuffs (against the Prince of Wales’s Wedding) that ever was known,” the London Daily Post announced, “and those that are now made, are reckon’d the richest Patterns ever seen.” Indeed, individuals of rank were invited to view Augusta and Frederick’s wedding clothes displayed in their newly renovated apartments at Kensington Palace in the week prior to their betrothal. [15] Charles Philips also painted a three-quarter-length portrait of England’s newest princess in her heavily embroidered couture silver dress, topped with ermine-lined state robes, and the acclaimed engraver John Faber Jr. soon after produced a mezzotint copy of the picture for consumers. [16]

By the 1730s, then, the royal wedding was invented as a theatrical and theatricalized spectacle of statecraft and romance, fostered through the commercialized newspaper and periodical press and a growing marketplace in regal pictures and objects. The eighteenth century was the great age of celebrity, Joseph Roach has argued, engendered through media representations, especially the circulation of charismatic stage icons and cultural luminaries who stoked desire by offering spectators the illusion of intimacy despite the reality of physical inaccessibility. [17] Whereas we are quick to recognize the theatricality and affective appeal of Victorian monarchy, which permitted consumers to imagine personal attachments to individuals whom they would never meet in real life, I want to draw attention to the ways in which the early Hanoverian royal family was adapting to and adopting the characteristics of celebrity culture (whether they were entirely reluctant to do so, like George II, or eager to chase popularity, like Prince Frederick). Newspapers offered new possibilities of royal publicity, allowing spectators access to exclusive palace rooms, court finery, and the nuptial bed in completely novel ways that mark an abrupt departure from discussions of state weddings in the later Stuart period. At the very least, we should recognize that our contemporary fascination with royal engagements and the extravagant wedding dresses worn by English princesses has an eighteenth-century origin—for better, (or) for worse.

Notes

[1] For further reading, see Carole Levin, Heart and Stomach of a Queen: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Sex and Power (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994), chapter 3; Kevin Sharpe, The Personal Rule of Charles I (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992); Laura Lunger Knoppers, Politicizing Domesticity: From Henrietta Maria to Milton’s Eve (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Andrew C. Thompson, George II: King and Elector (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), chapter 1; Marilyn Morris, Sex, Money, & Personal Character in Eighteenth-Century British Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014); Thomas Lacquer, “The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics as Art in the Reign of George IV,” Journal of Modern History 54 (1982): 417-66.

[2] “Queen Victoria’s Bridal Colour,” Woomer’s Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 11 January 1840, 2504. On the tension between domesticity and sovereignty in representations of Victoria as bride, wife, and mother, see John Plunkett, Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 29-35; Margaret Homans, Royal Representations: Queen Victoria and British Culture, 1837-1876 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 17-32.

[3] “Marriage of Queen Victoria,” The Bradford Observer, 13 February 1840, Issue 314.

[4] “Royal Marriage,” The Blackburn Standard, 12 February 1840, Issue 265. See also “Marriage of the Queen,” The Morning Post, 11 February 1840, 21542.

[5] See, for instance, British Museum: 2006,U.2079; 1902,1011.886; 1894.0516.59; and 1902,1011.8909.

[6] See Hannah Smith, Georgian Monarchy: Politics and Culture, 1714-1760 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Hannah Greig, The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 99-130.

[7] For excellent discussions of William’s recovery and his wedding to Princess Anne, see Marilyn Morris, Sex, Money and Personal Character, 103-09, and Thompson, George II, 108-13.

[8] The Daily Journal, 26 February 1734, Issue 4091; Penny London Post, 27 February 1734, Issue 80.

[9] Jacques Rigaud after William Kent, The Wedding of Princess Anne and William of Orange in the Chapel of St. James’s as Decorated by William Kent, 1734. National Portrait Gallery, NPG D32900.

[10] Daily Journal, 16 March 1734, Issue 4107, and 18 March 1734, Issue 4108; London Evening Post, 14-16 March 1734, Issue 986; Penny London Post, 18 March 1734, Issue 88; and Penny London Post, 19 October 1733, Issue 24.

[11] Greig, The Beau Monde, 119-25; Hannah Smith, “The Court in England: 1714-1760: A Declining Political Institution?” History: The Journal of the Historical Association 90.297 (January 2005): 23-41.

[12] See British Museum: Anonymous unmounted engraved paper fan, c. 1734-35, 1891,0713.375; Martha Gamble, Unmounted fan-leaf with orange tree, rose bush, and poem celebrating the marriage of Princess Anne, c. 1734-35, 1891,0713.426; Qing Dynasty Porcelain Bowl, c. 1734, Franks.1447.

[13] Daily Gazetteer, 27 April 1736, Issue 260; Reads Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, 1 May 1736, Issue 608; Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal 28 February 1736, issue 386. See also 20 March 1736, issue 389.

[14] For instance, see Reed’s Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, 1 May 1736, Issue 608; London Evening Post, 27-29 April 1736, Issue 1318.

[15] London Daily Post and General Advertiser, 2 April 1736, Issue 443, and 17 April 1736, Issue 456; London Evening Post, 13-15 April 1736, Issue 1312.

[16] Charles Philips, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, Princess of Wales, c. 1736, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2093; John Faber Jr, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, after Charles Philips, c. 1750, National Portrait Gallery, NPG D10778.

[17] Joseph Roach, It (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2007).

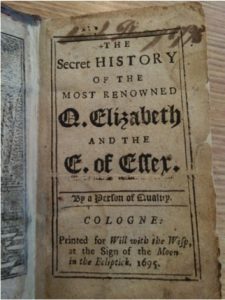

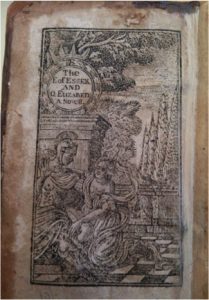

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs.

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs. Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.

Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.