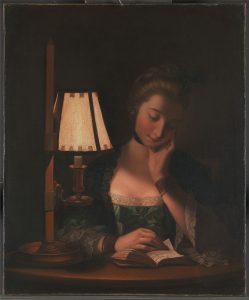

Francis Wheatley, 1747–1801, British, The Mistletoe Bough, ca. 1790, Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.117.

References to the celebration of Christmas have appeared in British literature for centuries, and at the earliest, in a context that combines Christian and pagan elements from Winter solstice celebrations that included decking the halls with holly and evergreens, and caroling. Peter Brown writes that “the earliest reference to what we now accept as Christmas Day is in the Roman Chronograph of 354 AD, citing the birth of Christ as being on December 25th.”[1] Recognizing this traditional date, Britain realized cultural changes over centuries that refined their customs and practices in celebrating their Christian holiday, but the long eighteenth century, influenced early on by the rigidity of the Puritans, proved to be the transitional century for future Christmas celebrations in England.

For medieval literature’s pagan/Christian Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a Christmas celebration is essential for staging the approaching adventure. The poet tells us, “It was Christmas at Camelot—King Arthur’s court …. [and] feasting lasted a full fortnight and one day, / with more food and drink than a fellow could dream of” (FITT I.37 and 44-45). On New Year’s Day, Gawain’s quest begins, as the Green Knight, holding a sprig of holly and an axe, appears in the hall, and only Gawain accepts his challenge. The envelope poem concludes at the next New Year’s celebration, as Gawain is returned safely to Camelot, having proved himself equal to the Green Knight and his materializations.[2]

Sixteenth-century poet Thomas Tusser (c. 1520-80) later describes the essence of the holiday in his “Christmas Cheer”:

Good bread and good drink, a good fire in the hall

Brawn, pudding and souse, and good mustard withall:

Beef, mutton and pork, shred pies of the best:

Pig, veal, goose and capon and turkey well drest:

Cheese, apples and nuts, jolly carols to hear,

As then in the country is counted good cheer.[3] (lines 5-10)

Other early references to Christmas, explains Brown, remind us of the custom of the yule log and of the ancient Wassail bowl (mulled wine today); they also refer to the hospitality in the English country houses that “imply an almost ‘open-house’ policy for the 14 days from Christmas Eve to Epiphany.”[4]

The Renaissance is graced with a pagan, long, and boisterous post-Christmas Day celebration in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, probably written to be performed on the twelfth day of Christmas (January 6, the Feast of Epiphany) to herald the end of twelve days of merry making. Shakespeare alludes to the season in a few other plays, such as As You Like It and Taming of the Shrew; but his holiday references are mostly associated with snow, gaming, drinking, and revelry—he rarely uses the word “Christmas,” Love’s Labour’s Lost being an exception: “At Christmas I no more desire a rose / Than wish a snow in May’s new-fangled shows” (1.1.105-106).[5] Literary rival Ben Johnson, however, penned a short play in December 1616 entitled Christmas, His Masque, to be performed in church. Yet these medieval and Renaissance works relate more to ancient customs and practices than to the more refined celebrations that would develop in later centuries.

Typically, we begin to associate Christmas in literature with the nineteenth century, thanks to Charles Dickens’s 1843 A Christmas Carol and his less popular 1844 story The Chimes, as well as a Christmas chapter in Pickwick Papers. Other nineteenth-century works emphasizing the holiday in some way include Sir Walter Scott’s In Olden Times, Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, various holiday scrap books, and a Christina Rossetti poem, later the lyrics for “A Christmas Carol,” comprising the following familiar lines:

In the bleak mid-winter

Frosty wind made moan,

Earth stood hard as iron,

Water like a stone;

Snow had fallen, snow on snow,

Snow on snow,

In the bleak mid-winter

Long ago.[6] (lines 1-8)

Twelfth-Night festivities continued to be popular in the nineteenth century until 1870, when Queen Victoria “objected to the riotousness of the occasion,” making it “the one Christmas tradition that was quelled by the Victorians rather than enhanced.”[7] Christmas was also a lucrative time for authors and publishers to bring out new works, as Dickens well knew. The Victorian era also made Christmas cards and Christmas trees fashionable in upper-class homes.[8] Thus, the nineteenth century represents a cultural shift in the way Christmas was celebrated and documented, but that shift occurred very gradually during the long eighteenth century.

Regrettably, this cultural change is sparsely recorded in the literature of the long eighteenth century, with only a few examples of how people in England celebrated the season. Thanks to Julie Ratcliffe’s British Library website, entitled “An 18th-Century Christmas,” we have limited examples from the library’s archives, and these mostly for lesser-known works. But again many of those address the winter season rather than the actual holiday celebration that later evolved. John Milton’s On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity was published in 1645, but Ratcliffe reminds us that, a short time later, Cromwell’s government banned Christmas celebrations, which were not fully resumed until after the Restoration.[9] The Geffrye Museum’s Simon Carter argues that the Puritans “disapproved of Christmas for what it had become—an excuse for insobriety, gluttony and gambling…. Extreme Protestants also believed that there was no justification for the celebration of Christmas in the scriptures.”[10] As a result, the Puritan ban prompted cultural changes in holiday celebrations that would shape how people in eighteenth-century Britain kept Christmas, resulting in a rather colorless holiday that would not transform significantly until late in the century and early in the nineteenth, as Jane Austen’s novelistic depictions added a holiday ambiance for her readers.

Ratcliffe affirms that although Christmas throughout the long eighteenth century meant lean times for the poor, as most work stopped for the holidays without pay to workers, more benevolent landowners provided them with gifts of money and food. Wealthy and poor alike, she continues, decorated their homes with greenery: ivy, mistletoe and herbs, including rosemary and bay. People reunited and played games, wassailers sang carols, and theaters even performed plays—all remnants of pagan times and winter solstice celebrations, as were the colors red and green. Yet, “Christmas festivities during the eighteenth century,” writes Simon Carter, “were much more restrained than those of the previous century.”[11] I argue that this was a direct result of Puritan mindsets that shaded mid-seventeenth-century public celebrations.

A British Library anthology entitled A Literary Christmas (2013) provides excerpts of Christmas texts by authors from the seventeenth- through the twenty-first centuries, including Milton’s 1645 poem mentioned above, but eighteenth-century examples are scarce. Restoration diarists John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys do write about their movements and encounters during the holidays, mostly revolving around church, family, and food. Christmas Day 1660 would have been the first public Christmas celebration in England in fourteen years, for in 1657 Evelyn recorded the following experience under Cromwell’s reign:

I went to London with my wife, to celebrate Christmas day, Mr Gunning preaching in Exeter chapel …. Sermon ended, as he was giving us the Holy Sacrament, the chapel was surrounded with [Parliamentary] soldiers, and all the communicants and assembly surprised and kept prisoner by them.… It fell to my share to be confined to a room … where yet I was permitted to dine with the master of it … and some others of quality who invited me. In the afternoon came Colonel Whalley, Goffe, and others … to examine us one by one; some they committed to the marshal, some to prison.[12]

After the Restoration, Charles II lifted the ban on Christmas celebrations, and Evelyn’s December and January entries return to recorded church services and reunions with friends.

Samuel Pepys, too, chronicles several Christmas days in his life, and on December 26, 1662, he writes that he was up early, his “wife to the making of Christmas pies all day.”[13] His Christmas reflections are again about attending church and about reunions and dining with his wife and friends. On Christmas day 1666, he records that he,

Lay pretty long in bed, and then rose, leaving my wife desirous to sleep, having sat up till four this morning seeing her mayds make mince pies. I to church where our parson Mills made a good sermon. Then home, and dined well on some good ribbs of beef roasted and mince pies.[14]

Always the public man, Pepys recollects on January 6, 1667, that throughout the season he has been “enjoying [himself] mightily to have friends at [his] table.”[15] Pepys’s Christmas celebrations were probably typical for middle-class Londoners, but during the entire holidays, he continued to travel back and forth to his government office to take care of pending business.[16]

While Evelyn and Pepys write openly about their personal Christmas celebrations with gatherings in both their private and public spheres, Jonathan Swift complains to Stella on December 26, 1710 (Boxing Day), that Christmas simply signals additional expenses:

By the Lord Harry, I shall be undone here with Christmas boxes. The rogues of the Coffee-house have raised their tax, everyone giving a crown; and I gave mine for shame, besides a great many half-crowns to great men’s porters, etc. (Letter XII).[17]

Certainly, it would have been out of character for Swift to write about the joys of Christmas!

Although Christmas day in the eighteenth century meant attending church, it also meant celebrating with family, with a focus on food—especially the Twelfth Night Cake. Dr. Johnson recounts that “People used to stop and stare into the windows of pastry cooks at the gorgeous Twelfth Night Cakes on sale.” And in his January 6, 1763, diary entry, James Boswell records his indulgence in those cakes, writing that he “took a whim that between St Paul’s and the Exchange and back again” he moved to “different sides of the street” to “eat a penny twelfth-cake at every shop” where he could get one. “This I performed most faithfully,” he writes. But at the same time Boswell laments his lack of a home in which to celebrate:

I regretted much my not being acquainted in some good opulent City family where I might participate in the hearty sociality of the ancient ceremony of the Twelfth-cake. I hope to have this snug advantage by this time next year.[18]

A recipe for Johnson and Boswell’s referenced fruit cakes can be found in John Mollard’s 1808 The Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined, Comprising Ample Directions for Preparing Every Article Requisite for Furnishing the Tables of the Nobleman, Gentleman, and Tradesman, as follows:

Take seven pounds of flour, make a cavity in the center, set a sponge[19] with a gill and a half of yeast and a little warm milk; then put round it one pound of fresh butter broke into small lumps, one pound and a quarter of sifted sugar, four pounds and a half of currants washed and picked, half an ounce of sifted cinnamon, a quarter of an ounce of pounded cloves, mace, and nutmeg mixed, sliced candied orange or lemon peel and citron. When the sponge is risen mix all the ingredients together with a little warm milk; let the hoops be well papered and buttered, then fill them with the mixture and bake them, and when nearly cold ice them over with sugar prepared for that purpose as per receipt or they may be plain.[20]

For those who could not afford these opulent cakes, however, some bakers offered less expensive miniatures in the form of decorated buns. The celebration also included mince pies, plum porridge, and Yorkshire puddings made with turkey and other fresh game birds. Meat and vegetable Yorkshire pies were traditional, and in 1747 baker Hannah Glasse, along with a reference to her recipe, writes that “The pies are often sent to London in a box as presents; therefore the walls must be well built.”[21]

There are also records that confirm some Londoners retreated to the country to celebrate the season. Writer and reformer Elizabeth Montagu (1718-1800) recorded just before Christmas 1781 that at this time of the year,

… the great city is solitary, silent, and quiet. Its present state makes a good preface to the succeeding months of crowd, noise, and bustle…. One always finds some friends in town; a few agreeable people may at any time be gathered together; and, for my own part, I think one seldom passes the whole of one’s time more agreeably than before the meeting of Parliament in January.[22]

In addition to these personal anecdotes about the season, one must not forget the Christmas carols that eighteenth-century English musicians and lyricists afforded. As Rossell Robbins maintains in Early Christmas Carols, while authorities such as Julian’s Dictionary of Hymnology (1892) and the Oxford Book of Carols (1928) define English carols as a kind of lyrical poem usually with a religious emphasis, “the earliest carols had a rigid literary and musical form, designed for a specific function,” and

The true carol is to be distinguished from a hymn or a religious song. When it was a living form, the carol always had set stanzas (generally quatrains) alternating with a “burden,” two lines sung at the beginning of the carol and repeated after each stanza. The carol, therefore, is strictly a forme fixe, just as precise as the French art patterns of ballade, triolet, or rondeau (and just as dissimilar).[23]

According to Robbins, the first medieval carols appear in only four manuscripts from the early fifteenth century, and most commemorate Christmas Day, but there are only some fifty actual carols written after 1600—and they were more secular,[24] performed outdoors and in family gatherings but not at religious services.

Whether or not they adhere to the carol format that Robbins defines, the eighteenth century provides many memorable Christmas songs. “Christians Awake” was written by John Byron of Broughton, England, in 1692; “Oh Come All Ye Faithful” is attributed to Englishman John Wade in the early 1700s; “Joy to the World,” based on Psalm 98, was written by Isaac Watts in 1719; and “Hark the Herald Angles Sing” was written by Charles Wesley (brother of John Wesley) in 1739. Playwright and poet Nahum Tate even contributed “While Humble Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” in the late sixteenth century. In fact, the British Heritage Centre explains that

The Book of Common Prayer offered no specific provision for seasonal hymns, and it was only when poet laureate Nahum Tate’s “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks By Night” was included in the 1700 Supplement to the New Version of the Psalms that a Christmas hymn was permitted to be sung in Anglican services.[25]

However, those carols written by dissenters such as Watts and Wesley would not have been permitted in the Anglican Church but may have been sung in Methodist services. German carols appeared during the century as well.[26] But whether or not allowed in the established church of England, these carols were essential for the season’s secular gatherings.

Along with carols embracing the sanctity of Christmas, many ministers advocated charity from the pulpits and inspired affluent Britons to focus on holiday goodwill. Sarah Lloyd highlights the charity events associated with eighteenth-century Christmas holidays. As interests in charitable events gained momentum during the century, so did fundraising events as benevolent societies “courted middle and upper-class Londoners with invitations to concerts and exhibitions.” Further,

Toward the end of the year, they might pay half a guinea each to hear Handel’s Messiah in the Foundling Hospital Chapel or go to Covent Garden and Drury Lane to watch tragedies and farces. Charitable activities extended beyond churches, alms, and sermons into the theatre.[27]

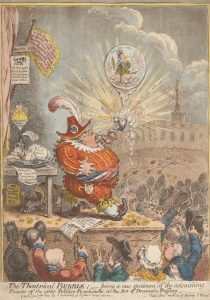

Another seasonal entertainment is Davis Garrick’s pantomime, colorful but secular, entitled A Christmas Tale: In Five Parts, performed at Drury Lane in 1773, with sets created by painter/stage designer Phillip de Loutherbourg (1740-1812) and music by Charles Dibdin (1745-1814).[28] This tale, probably based on several earlier sources,[29] is about Christmas only in its reference to food, festivity, contrary spirits, and Tycho’s line: “you know where to send for some plumb cake, this holiday time.”[30] Although the play was performed regularly during the season, it is essentially the love story of Camilla and Floridor, plagued by the antics of holiday spirits that keep them apart. Robert Fahrner writes that Charles Dibdin’s evolving songs for A Christmas Tale were so criticized by Garrick that Dibdin resolved that “he would write music so flexible that ‘if any alterations were suggested, they would not materially affect the drift of the air.’”[31] And while contemporary reviews lauded de Loutherbourg’s artistic settings, they judged Dibdin’s music as the worst he’d ever composed or, at best, just agreeable. Regardless of the criticism, A Christmas Tale ran for seventeen performances in its first season, and Dibdin made a profit, even though he complained both about his compensation and his ill treatment from Garrick.[32] As a result, in 1788, explains Valentine Barrow, Dibdin struck out on his own as a solo entertainer, and “Contemporary comment indicates that [he] was a skilled lyricist, composer, script writer and performer.”[33] In “Harlequin Britain,” John O’Brien maintains that “the segregation of pantomime to essentially a seasonal entertainment” was usually “associated with Christmastime,” and harlequin and pantomime were both linked to Garrick.[34]

A rarer holiday play, printed in 1788, is Alexander, and the King of Egypt. A Mock Play, As it is Acted by The Mummers every Christmas. Mummers plays had been a middle- and lower-class tradition in Ireland, England, and Scotland for centuries and usually featured a Christian character (often based on St. George) who defeats a threatening non-Christian, often from Turkey or Egypt. Ben Johnson’s A Masque for Christmas, mentioned earlier, represents such a play written for the church. In English Mummers and Their Plays, Alan Brody explains that these plays have the “same, recognizable shape. Yet no two are exactly alike…. They are all seasonal and they all contain a death and resurrection somewhere in the course of their action.” Some include sword play and some do not, and the plays would have been performed by men, at times travelling as troupes throughout the countryside and clothed in elaborate disguises.[35]

Alexander, and the King of Egypt is an anonymous, brief three-act tragedy that opens as Alexander presents three actors from Italy: a noble King, a good Doctor, and a miser called Old Dives. After the actors remind the audience that it is Christmas Time, they are followed by The King of Egypt and his son Prince George.[36] But the festivities turn tragic as Alexander stabs the arrogant Prince in a sword fight and later kills the King of Egypt. The mummers conclude:

… Christmas comes but once a Year;

Though when it comes, it brings good Cheer,

But farewell Christmas once a Year.

Farewel, farewel, adieu! Friendship and Unity.

I hope we have made Sport, and pleas’d the Company;

But, Gentlemen, you see we’re but young actors four,

We’ve done the best we can, and the best can do no more.[37] (Act 3)

Since the King of Egypt refers to Alexander as a “Curs’d Christian” early in the play, we must assume that, like most mummers plays, this is a battle between good and evil—Christianity versus the “paganism” of Egypt’s ancient culture and polytheistic beliefs. In Brody’s definition the action would be considered as “sword play,” but this play is not included in his list of archived mummers plays. Further, while Paul Griener’s “The Fascination with Egypt During the Eighteenth Century” expounds on the attraction to Egypt’s contradictory artistic, secular, and Biblical significance,[38] Alexander, and the King of Egypt, like many mummers plays, focuses instead on a Middle Eastern threat to Christianity. These mummers plays are a research project in themselves.

Another Christmas oddity appearing in England a few years earlier in 1779 is Baroness Elizabeth Craven’s Modern anecdote of the ancient family of the Kinkvervankotsdarsprakengotchderns: a tale for Christmas, dedicated to Horace Walpole.[39] Craven wrote a few moderately successful farces, pantomimes and fables, some of which were performed, and she became friends with Walpole, Samuel Johnson, and James Boswell. She explains in the first part of the tale that she will shorten the antagonist’s title to “the Baron” so that the reader “may not break his teeth,” and she begins by describing the Baron’s manor as being hung from floor to ceiling with ancestral portraits. These pictures represent most of the Baron’s society, excepting a distant relative, Hogresten (who dreams himself a knight), a chaplain, and a beautiful and talented daughter, Cecil.[40]

Cecil is a prisoner in her father’s manor, for he will not let her marry beneath her—beneath his ancestors, that is. But when a friend of her late mother visits the manor with her son Frederic Franzel, the two young people fall in love. In the second part, Craven reminds the skeptical reader that there is “such a thing as love at first sight.”[41] The Baron is not pleased, and Hogresten is jealous, but Madame Franzel determines to make a match between Cecil and her son. When young Franzel loses his way in the manor one night and accidentally ends up in Cecil’s bedchamber, the two young lovers are at first flustered but soon give way to all their passions. The next morning Madame Franzel, who knows nothing about the previous evening’s encounter between the lovers, proposes a match between Frederic and Cecil to the Baron. He indignantly refuses, citing 500 reasons—500 ancestors—that make the match impossible. Once the Franzels leave the manor, Cecil becomes as “inanimate as one of the canvas ancestors.”[42] But Cecil soon receives a letter from Madam Franzel; a personal note from Frederic about their “ties” falls out of the letter. The Baron is angry and determines he will marry Cecil to Hogresten. The author interrupts here with, “I believe, they were the only two men existing, who were glad that their young female relation should not be married to a man who had passed the night in her room.”[43] Hogresten imposes himself upon Cecil as a potential husband, but she adamantly refuses—her father tells her that she will be a prisoner until she consents, so she pretends to do so. The innovative young woman then informs her father that she would like to “clean up” all those ancestral portraits but needs a ladder for her work, meanwhile sending a note to her lover about her planned escape. As Frederic waits below, she takes down the paintings and piles them up at the window to give herself leverage—then springs from the window. Craven assures the reader that she is now happy in Frederic’s arms, Hogresten returns to dreaming of being a knight, and her father the Baron continues to be absorbed in the past. But the portraits of these constrictive ancestors turn out to be the physical means of her independence and happiness in the end. So while this story claims to be a tale for Christmas, like Garrick’s A Christmas Tale and the anonymous Alexander, and the King of Egypt, it is not about Christmas at all, lacking even a meager symbol of the holiday season. Craven’s story is an example in the pattern of eighteenth-century literature’s lack of emphasis on Christmas, itself a tale for the season but not an example of the season. While it appears that eighteenth-century Londoners were going out for entertainment during the holidays, their entertainments were lacking in Christmas themes, culturally separating them from the boisterous medieval and Renaissance celebrations that rang in the holidays long before the Puritan influence of the mid-seventeenth century.

Finally, in a poetical turn to Londoners’ public spirit during the Christmas season, John Gay joyfully observes people as they walk about the city streets. In his 1716 poem Trivia: or, The Art of Walking the Streets of London, in whose “Advertisement” he pays tribute to his friend Swift, he observes people, surroundings, and action. The poem provides a vivid cross section of Londoners, and a few lines in Book II focus on the festive holiday season as follows:

When rosemary, and bays, the Poet’s crown,

Are bawl’d in frequent cries, through all the town,

Then judge the festival of Christmas near,

Christmas, the joyous period of the year.

Now with bright holly all your temples strow,

With lawrel green, and sacred mistletoe.

Now, heav’n-born Charity, thy blessings shed;

Bid meagre Want uprear her sickly head:

Bid shiv’ring limbs be warm; let plenty’s bowle

In humble roofs make glad the needy soul.

See, see, the heav’n-born maid her blessings shed;

Lo! meagre Want uprears her sickly head;

Cloth’d are the naked, and the needy glad,

While selfish Avarice alone is sad.[44] (lines 437-50)

Wishing all Londoners equal blessings, Gay addresses both the joys and the realities of the holiday, as the poor still have need, want, and sickness. According to biographer Calhoun Winton, Gay’s poem was an immediate success, and his friend Dr. Arbuthnot even claimed that “Gay has gott so much money by his art of walking the streets, that he is ready to sett up his equipage.”[45] Winton argues that the poem, “among its other qualities,” has “dramatic value” as “an embodiment of London in action,” providing in its descriptions a kind of cinematic quality for the reader.

Later in the century a poem by Robert Southey, entitled “A Poem for Christmas Day 1795,” upholds Gay’s festive eighteenth-century picture,

How many hearts are happy at this hour

In England! Brightly o’er the cheerful hall

Flares the heaped hearth, and friends and kindred meet,

And the glad mother round her festive board

Beholds her children, separated long

Amid the wide world’s ways, assembled now —

A sight at which affection lightens up

With smiles the eye that age has long bedimm’d

I do remember, when I was a child,

How my young heart, a stranger then to care;

With transport leap’d upon this holyday,

As o’er the house, all gay with evergreens,

From friend to friend with joyful speed I ran,

Bidding a merry Christmas to them all.[46] (lines 1-14)

For the eighteenth century, it is mostly the poets and lyricists who acknowledge Christmas as a time of good cheer.

While we do have limited narratives, poems, and lyrics (mostly carols) that focus on Christmas as it relates to religion, festivities, homecomings, and food, most eighteenth-century novelists (e.g., Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne, and Elizabeth Inchbald) avoid Christmas celebrations in their novels altogether. Nevertheless, in his self-published A Ghost of an Idea: Dickens, Daniel Defoe, and the Supernatural Origin of A Christmas Carol, Steve Bivens argues that Dickens relied on Defoe’s 1726 story “The Friendly Demon,” in which he introduces a ghost “dead these seven years,” to inspire the apparition of Marley in A Christmas Carol.[47] This story, allegedly told by the blind visionary Duncan Campbell, relates a great affliction brought upon him in 1717 causing “fits” and disabled speech and movement. After attempting a cure from the cold baths near Sir John Oldcastle’s, he takes his bed but is later awakened by a

Guardian Angel, Cloth’d in a white Surplice like a singing Boy … holding a Scrowle … in his right Hand, whereon he is given instructions for a cure involving magnets and a powder; a postscript even tells us that we may purchase the prescriptive powder at Dr. Campbell’s house near Charing Cross.[48]

The claim of this influence on Dickens implores examination. Defoe did not write “The Friendly Demon,” like many pamphlets and other works mis-attributed to him. He did write about the supernatural in works such as A True Relation of the Apparition of one Mrs. Veal (1706), A Political History of the Devil and A System of Magick (both in 1726), and An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions (1727), etc., but this is not one of them.[49] Defoe’s bibliographers P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens have no record of the alleged “Friendly Demon”[50] and even list the work in their 1994 bibliography entitled Defoe De-Attributions as belonging to another author.[51] That said, spirits appeared in early Christmas tales long before Dickens, even in Garrick’s A Christmas Tale, so his Marley could have been influenced by any number of stories—if at all.

The most consistent novelistic emphasis on Christmas celebrations, nonetheless, can be attributed to Austen in the early 1800s. There are also a few of her family letters that mention Christmas, usually in the context of the weather or an approaching holiday ball. Austen’s novels regularly associate the holiday with snow, food, and seasonal balls, especially, Mansfield Park (1814), Persuasion (1817), and Emma (1815). And a brief mention of the holiday comes near the end of Pride and Prejudice (1813), as Elizabeth Bennet invites her aunt Gardiner to come to Pemberley at Christmas to usher in the new family’s festivities.

In Jane Austen’s Christmas, Maria Hubert invites us to imagine,

… putting on a fine ballgown … floaty and clinging, leaving no room for flannel petticoats, your hair dressed in such a way that only the flimsiest scarf can protect your head from the cold night. The coach offers little protection, draughty. What you need when you arrive at the Christmas Ball is a bowl of soup to put colour in the cheeks before greeting the other guests and old acquaintances there, already glowing from their own partaking of the soup, the wine and the dancing. Such would have been the experience of Jane and her characters at every winter ball they attended. She tells us in her novels that such a soup, fortified with ‘negus’—a mixture of hot water mixed with sweet wine and lemon … was considered a necessity on these occasions.[52]

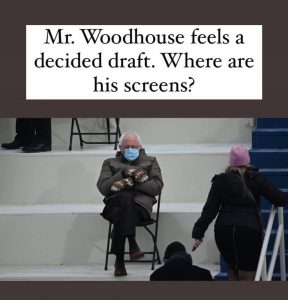

This reconstruction of Christmas in Austen’s world recaps scenes in her novels. Christmas is mentioned early in Mansfield Park as the excitement surrounding the December 22 ball mounts throughout the day. The holiday is also a setting for several chapters in Emma, but in one episode the celebration with family is tense, as Emma’s neurotic father, Mr. Woodhouse, dreads traveling in the snow to dine with the Westons at Randalls. Austen writes that “The evening before this great event (for it was a very great event that Mr. Woodhouse should dine out, on the 24th of December) had been spent by Harriet at Hartfield, and she had gone home … with a cold….”[53] The potential spread of Harriet’s cold and the beginning of a light snow provokes a flurry of indecision about going out at all, but the Christmas visit finally occurs, fraught with romantic misunderstandings. In Persuasion the focus is on family and food, as Mrs. Musgrove is surrounded by the “little Harvilles” ready to celebrate the holiday:

On one side was a table, occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn [potted meat with jelly] and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others.[54]

Austen’s holiday descriptions are a segue into how Christmas would later be observed by the Victorians, moving away from ultra-conservative Puritan ideas to a family-structured way of celebrating—making the long eighteenth century the transitional period to a more refined cultural experience, the pivotal century between the seventeenth and the nineteenth.

So while many traditional Christmas celebrations were remnants of earlier pagan roots, eighteenth-century British upper classes may have deliberately shunned the riotous twelfth-night festivities of the lower classes to present a more cultured and enlightened front for their century. As Carter explains, celebrations were more restrained; and “While the passing of customs such as wassailing, mummers or dragging in the yule log might have been lamented, it is likely that most nineteenth-century,” and as I add, eighteenth-century as well, “ladies and gentlemen would, in reality, have found such behaviour raucous, drunken or vulgar… a new way of celebrating was needed.”[55] These “raucous” celebrations in the public sphere may have been reserved for bringing in the new year, but Christmas itself was still regarded as sacred. Carter reminds us that “the main occasion for giving gifts was still New Year,” also a “time for the giving, or collection, of Christmas boxes.” He further explains that “By the eighteenth century, Christmas boxes of larger amounts were demanded … by most servants and tradesmen”[56]—just as Swift complained. And since Restoration England had to recover from the Puritan ban on Christmas, under Cromwell’s long dictatorship apprehensive families may have simply abandoned their earlier Christmas traditions.

Ultimately, while the century’s literature may not stand up to the colorful Victorian literary emphasis on lavish Christmas celebrations with large families, at least some writers in the long eighteen century reveled in the season, a season then about religion, food, family, and friends—a season lacking the commerciality of today.

Notes

[1]. Peter Brown, The Keeping of Christmas: England’s Festive Tradition, 1760-1840 (York, UK: York Civic Trust, 1992), 4. With the advent of the Gregorian calendar, mathematical computations provide different dates.

[2]. Anonymous, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Vol. A, 10th ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2018), 204-205.

[5]. William Shakespeare, Love’s Labour’s Lost, in The Riverside Shakespeare (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974), 1.1.105-106.

[6]. Christina Rossetti, “A Christmas Carol” at https://poets.org/poem/christmas-carol, accessed 12 July 2021.

[7]. Maria Hubert, Jane Austen’s Christmas: The Festive Season in Georgian England (Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton, 1996), 87.

[9]. Julie Ratcliffe in The British Library’s “An 18th-Century Christmas” at https://www.julieratcliffe.co.uk/an-eighteenth-century-christmas. Accessed 13 June 2021.

[10]. Simon Carter, Christmas Past, Christmas Present: Four Hundred Years of English Seasonal Customs, 1600-2000 (London: Geffrye Museum Trust, 1997), 11.

[12]. John Evelyn, Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, F.R.S., A New Edition in Four Volumes (London: Colburn, 1850), 323.

[13]. Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, 10 vols. (New York: AMS Press, 1968), 2:425.

[16]. There are references to a 1686 play attributed to Josiah King entitled The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas, Together with his Clearing by the Jury, followed by the Afternoon Tryal of Christmas. The first sketch shows up again in 1937 (Chicago publication) and is attributed to Walter Schmauch. I have been unable to authenticate either of these texts.

[17]. Jonathan Swift, Journal to Stella, Letter XII, at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4208/4208-h/4208-h.htm, accessed 11 July 2021.

[18]. James Boswell, Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, ed. Frederick A. Pottle (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1950).

[19]. The sponge and dough method is a two-step bread making process: in the first step a sponge is made and allowed to ferment for a period of time, and in the second step the sponge is added to the final dough’s ingredients, creating the total formula.

[20]. Quoted in Ratcliffe from Mollard’s 1808 The Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined, Comprising Ample Directions for Preparing Every Article Requisite for Furnishing the Tables of the Nobleman, Gentleman, and Tradesman at https://www.julieratcliffe.co.uk/an-eighteenth-century-christmas, accessed 13 June 2021.

[23]. Rossell Hope Robbins, ed., Early English Christmas Carols (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 1.

[24]. Robbins, 2 and 6. Brown writes that even Chaucer mentions “Karolying” in his Roman de la Rose (c.1360), 31.

[25]. See https://britishheritage.com/history/history-british-christmas-carols, accessed 19 February 2023.

[26]. See “10 Carols of the Eighteen Century” at https://www.history1700s.com/index.php/articles/25-society-and-culture/956-10-christmas-carols-of-the-18th-century.html, accessed 13 June 2021.

[27]. Sarah Lloyd, “Pleasing Spectacles and Elegant Dinners: Conviviality, Benevolence and Charity Anniversaries in Eighteenth-Century London,” Journal of British Studies 41.4 (2002): 23-24.

[28]. Garrick had tried his hand at another seasonal pantomime in December 1759 with Harlequin’s Invasion, a political satire, yet the play is an incomplete manuscript (John Larpent Plays).

[29]. See Robert Fahrner, The Theatre Career of Charles Dibdin the Elder (1745-1814) (New York: Peter Lang, 1989), 48. Fahrner suggests Favart’s La Fée Urgèle, Fletcher’s Women Pleased, and Dryden’s King Arthur.

[30]. David Garrick, A New Dramatic Entertainment Called A Christmas Tale. In Five Parts. As It Is Performed At The Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane (London: Becket, 1774), 5.1.

[33]. Valentine K. Barrow, “Charles Dibdin’s Entertainments” in Theatre Notebook 44.1 (1990):10-16.

[34]. John O’Brien, “Harlequin Britain: Eighteenth-Century Pantomime and the Cultural Location of Entertainments,” Theatre Journal 50.4 (1998): 504.

[35]. Alan Brody, The English Mummers and Their Plays: Traces of Ancient Mystery (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969), 3, 20, 24.

[36]. Anonymous, Alexander, And The King of Egypt. A Mock Play, As it is Acted by The Mummers every Christmas (Newcastle, 1788).

[38]. See Pascal Griener, “The Fascination for Egypt During the Eighteenth Century” in Beyond Egyptomania: Objects, Style and Agency, edited by Miguel John Versluys (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), 53-68. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110565843-006, accessed 2 January 2023.

[39]. Elizabeth Craven, Modern anecdote of the ancient family of the Kinkvervankotsdarsprakengotchderns: a tale for Christmas (1779), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/ecco/004842623.0001.000?rgn=main;view=fulltext, accessed 3 January 2023.

[44]. John Gay, Trivia: or, The Art of Walking the Streets of London, in The Poetical Works of John Gay (London: Oxford University Press, 1926), 2.437-450.

[45]. Calhoun Winton, John Gay and the London Theatre (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1993), 50-51.

[46]. Robert Southey, “A Poem for Christmas Day 1795,” https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/written-christmas-day-1795, accessed 6 January 2023.

[47]. Steve Bivens, A Ghost of an Idea: Dickens, Daniel Defoe, and the Supernatural Origin of A Christmas Carol (Independently Published, 2018).

[48]. Daniel Defoe, The Friendly Daemon; or the Generous Apparition; being A True Narrative of a miraculous Cure, newly perform’d upon that famous Deaf and Dumb Gentleman, Dr. Duncan Campbell, etc. (1726), at file:///Users/judithslagle_1/Desktop/Defoe-Demon-The%20Project%20Gutenberg%20eBook%20of%20The%20friendly%20daemon,%20or%20The%20generous%20apparition:%20being%20a%20true%20narrati.webarchive, accessed 18 July 2021.

[49]. See Paula Backscheider’s Daniel Defoe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 520.

[50]. P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens, A Critical Bibliography of Daniel Defoe (London: Pickering & Chatto, 1998), pages 72, 156, 228, 230, etc.

[51]. P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens, Defoe De-Attributions: A Critique of J. R. Moore’s Checklist (London: Hambledon Press, 1994), 141-42.

[52]. Maria Hubert, Jane Austen’s Christmas: The Festive Season in Georgian England (Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton, 1996), 75.

[53]. Jane Austen, Emma (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 98.

[54]. Jane Austen, Persuasion, ed. Linda Bree (Canada: Broadview, 1998), 156.

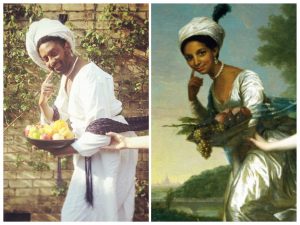

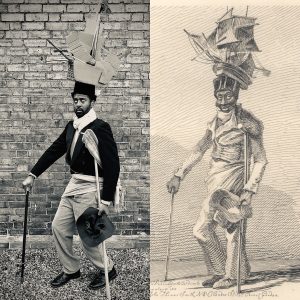

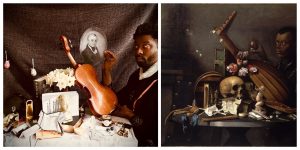

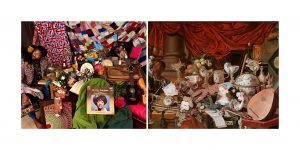

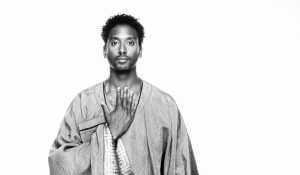

Peter Brathwaite is a British opera singer. After his degree at Newcastle University he trained at the Royal College of Music, London and Flanders Opera Studio, Belgium. Recent and future engagements include performances with the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Glyndebourne, La Monnaie, Nederlandse Reisopera, Opéra de Lyon and Opera North. He has written for The Guardian and The Independent. Documentary work includes BBC Radio 4’s Black Music in Europe 2, presented by Clarke Peters. He currently writes and presents features for BBC Radio 3’s Essential Classics. Peter is a Churchill Fellow, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and a Trustee of the Gate Theatre, London.

Peter Brathwaite is a British opera singer. After his degree at Newcastle University he trained at the Royal College of Music, London and Flanders Opera Studio, Belgium. Recent and future engagements include performances with the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Glyndebourne, La Monnaie, Nederlandse Reisopera, Opéra de Lyon and Opera North. He has written for The Guardian and The Independent. Documentary work includes BBC Radio 4’s Black Music in Europe 2, presented by Clarke Peters. He currently writes and presents features for BBC Radio 3’s Essential Classics. Peter is a Churchill Fellow, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and a Trustee of the Gate Theatre, London. Since January 2019, the S

Since January 2019, the S