When Lunardi, unpinion’d, first soar’d to the skies,

Huzza’d by the foolish, admir’d by the wise,

The Ladies all gaz’d with amazement and fear,

And from many bright eyes dropt the pitying tear;

The pitying tear he had when on high,

And from every fair bosom the heart-heaving sigh.

Now, clasping the thigh of each beautiful Miss,

He has soared within sight of the regions of bliss.

Alas! Should he lose his inflammable air,

The fears would return of each languishing fair,

Who hope he will rise like the Lark or the Dove,

His affections still set on the good things above.

(October 13, 1784, Morning Chronicle)

Figured as both an object of desire and a desiring subject, Lunardi’s inscription on ladies’ garters recast the sublime prospect of aerial views in the parodic terms suggested by the frisson of sexual voyeurism. Amidst all of the excitement in the weeks following the flight, this was clearly a joke worth overdoing. A poem which appeared on the same day on the final page of the Morning Post, this one signed by “G. S. C.,” entitled “On Seeing Lunardi’s Name Stamped on a Pair of new Garters, purchased by a Lady,” concluded that however dangerous Lunardi’s travel “upon the air’s uncertain tide”:

I own I envy when I see

Him twin’d about Maria’s knee;

The height of joy is surely this –

To have in sight the realms of bliss.

Three days later, another squib in the Morning Post, this one simply entitled “The Garter,” played on the same now-familiar double entendre:

As the high-tow’ring Eagle flies

Majestically through the skies,

So did the brave Italian soar,

Aerial regions to explore:

And when he came

To earth again,

Each British dame,

To crown his fame,

Below her knee, or round her thigh,

His dear enchanting name did tie;

And shew’d the bold advent’rer more

Of Heaven than e’er he saw before.

It is possible to make too much of these sorts of poems, which were only ever intended as the sort of lighthearted humour worthy of the back page of a newspaper, but collectively, they (and the fashion trend itself) dramatized the multiple ways that the rich but often turbulent connections between ideas about science (and more broadly, a commitment to the pursuit of knowledge in all its forms), commerce, and “the oceanic rumble” of everyday life were mediated by allusions to sexuality as an expression of both the buoyant spirit of innovation and the darker sense of transgression that were central to Britain’s experience of commercial modernity (De Certeau 5). As John Brewer has argued, efforts to forge a vision of Britain as a polite nation in which commerce was inseparable from emergent forms of sociability were unsettled by “the palpable intrusion of impulses – notably sexual passion and pecuniary greed – which were Rabelaisian and commercial and which undercut the claim that culture [or science] could and should be impartial, disinterested, dispassionate, and virtuous” (341).

If an account of Lunardi’s entrepreneurial efforts offers a history from below of the labyrinth of pressures and opportunities which constituted late eighteenth-century culture, comic references to “the good things above” and the persistent sexualization of ballooning references generally highlights the shaping force of the passions within this social and economic order. Lunardi was a leading target for these sorts of ironic sexual puns, but this line of humour was also true of a broad range of responses. An essay in the European Magazine gravely warned that, not only would “every nunnery” be “like a pigeon-house, with ladies like flocks of doves flying to and fro,” a situation which must inevitably lead to various “sad accidents,” but closer to home, “a young lady has nothing to fear from a flight from her chamber-window and back again, if she should not chuse to extend the trip to Scotland” (1785: 7: 84). The Air Balloon, A New Song linked ballooning, sexual promiscuity, and questions of cultural legitimacy by posing the question, “Should a child begot while they’re up in the sky. . . . To what parish on earth would the bantling belong?”

Lunardi’s flight might well have been hailed as cause for national celebration, the kind of extraordinary achievement that would enable “Neglected Science” to “raise [. . .] her head again,” as a more laudatory poem in the Morning Post suggested, but these various responses were also a reminder of the unsettling extent to which the hybridizing effects of commerce had blurred the distinctions between these different realms – the world of the mind and the body, enlightenment and fashion, science and sexuality, innovation and transgression (Oct. 1, 1784). If ballooning seemed to many observers to be a uniquely powerful symbol of Britain’s modernity (Thomas Carlyle would call it the “Emblem of much and of our Age of Hope itself”), these sorts of responses circulated as an equally striking index of the Rabelaisian nature of this social order (42). Or to put this in slightly different terms, Lunardi’s prominence as a figure of both scientific progress and satirical fun was due in part to the ease with which he could be invoked as a symbol of the discursive ecology that helped to render Britain’s modernity intelligible. And what may have enabled him to play this role most suggestively of all was the fact that he was foreign. In an age when the future itself often seemed foreign, Lunardi’s alterity offered an uncanny reminder of the radical ambivalence inspired by the “uncertain tide” of commercial modernity.

For his satirists, the fact that Lunardi was Italian only heightened the tendency to associate him with an irrepressible but potentially wayward sexuality. Love in a Balloon, which appeared in the Rambler’s Magazine on 1 November 1784, depicted Lunardi aloft embracing a female passenger (figure 1). “Ah Madame it rises majestically,” Lunardi exclaims. “I feel it does Signeur,” she answers, while on the ground admiring male spectators exclaim, “Damme he’s no Italian but a man every inch of him.” Lunardi’s gallantry might infuse his exploits with a romantic rather than a scientific edge, the print suggested, but at least it was England’s women to whom he was attracted. He was not, it turned out, quite so Italian after all. This particular pun was not restricted to Lunardi though. Dent’s British Balloon, and D– Arial Yacht (figure 2), which satirized Jean-Pierre Blanchard’s second ascent in England, at which the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Devonshire presided, recycled the same joke. The Prince, locked in a scandalous aerial embrace with the Duchess, exclaims, “it rises majestically,” to which the Duchess replies, “Yes, I feel it.” Watching from the ground beside the Duke of Devonshire, who complains of a headache, Lord John Cavendish announces, “His H—., no doubt, being a lover of the Science, will make some curious Experiments.” Lord Byron may have been creative, but he was hardly original in his comment about the reasons for a love-struck Don Juan’s contemplation of “air-balloons, and the many bars/To perfect knowledge of the boundless skies”: “If you think ‘twas philosophy that this did,/I can’t help thinking puberty assisted” (1: 92-93).

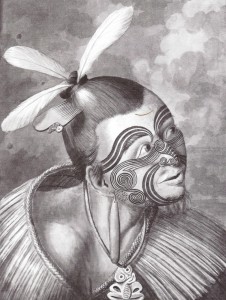

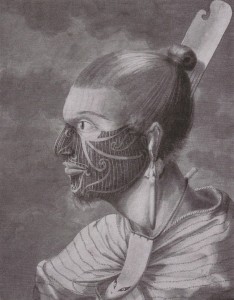

If satirical cartoonists were predictably attuned to the suggestive connections between ballooning and promiscuity, and more broadly, between the pursuit of knowledge and an endlessly shifting and vaguely defined play of desires (or between philosophy and puberty), their other important insight was the ease with which ballooning could be invoked to comment on a range of other social and political issues. The inclusion of the Prince and Duchess of Devonshire in Dent’s British Balloon, and D– Arial Yacht reflects this tendency to extrapolate from more straightforward depictions where ballooning featured as an object of sport and ridicule in its own right to satires where it stood in as an icon for political controversies. Predictably, the primary target was the doomed Fox-North Coalition. Dent’s The Political Parachute, A Coalition Experiment (figure 3) and E. Dachery’s The Coalition Balloon, 1784 (figure 4), which showed Fox and North being dragged by the neck by ropes hanging from a balloon, both offered complex political commentaries, the gist of which is summed up by Dent’s inscription: Death Blow to the Hopes. The Loss of Public Confidence, not restored by misleading the public opinion, and overthrowing the Propositions by gross inconsistency.” Three other 1784 prints, all by different artists, used balloon images to lampoon George III’s absolutist ambitions.[1]

In some ways, it was precisely this semiotic elasticity – the ease with which ballooning could mean so many different things to different people across a range of contexts – that made it so open to skepticism. Ballooning’s endless adaptability on a symbolic level reinforced its power to evoke the fluidity of a commercial society generally; its very ubiquity amongst these sorts of satires (many of which played on the idea of ballooning as a “bubble”[2]) made it an easily recognized symbol for all manner of foolish or unstable or disreputable behaviour in a social order where the very concept of value had floated free from its epistemological foundations.

If ballooning was, as Carlyle would suggest, the “emblem” of its age, it was in part because the physicality of the balloons themselves – simultaneously powerful and unguidable, scientifically ambitious and visually luxuriant, monumental and hollow – converged so suggestively with the endless range of incongruous activities, cultural domains, and symbolic registers within which ballooning flourished. The tensions between these various phenomena resonated with a much broader sense of the problems and possibilities of a highly commodified age in which the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge had become increasingly subject to pressures which unsettled the very idea of what counted as genuine knowledge or legitimate modes of dissemination. An interest in science, critics often worried, had been eclipsed by a love of spectacle. If their popularity reduced them to so many “philosophical playthings,” balloons circulated across the range of activities and venues which made up the world of fashionable sociability in ways that unsettled this distinction (Walpole 25: 542). As the wily Valet de Chambre in John Burgoyune’s The Heiress explained,

Nothing so easy as to bring every

Living creature in this town to the window: a tame

Bear, or a mad ox; two men, or two dogs fighting;

A balloon in the air – (or tied up to the ceiling ‘tis the

same thing) make but noise enough and out they come. (10)

None of the anxieties about the cultural “noise” of modern life that haunted the rage for ballooning during its early years – the unnerving overlap between the pursuit of knowledge and a craving for novelty, the impossibility of fostering a polite public culture (even one oriented towards scientific investigation) in ways that managed to keep its distance from the disruptive spectre of popular interest, the convergence between philosophy and puberty or polite sociability and Rabelaisian impulses, and the underlying problem of the hybridizing influence of commerce that ran through all of these concerns – none of these would have been lost on critics in the day. But neither was the undeniable power of the aspirations which also ran throughout these various elements of the balloonomania. However exasperating these aspirations might have been to some critics, they remained part of D’Alembert’s “effervescence of minds,” an expression of the age’s interwoven imperatives towards intellectual curiosity and fashionable indulgence, enlightenment and opportunism (qtd. Clark 7).

II

In recent years, the air ballooning craze of the 1780’s has been celebrated by historians such as Michael Lynn and Richard Holmes as a compelling example of the radical interfusion of those social and intellectual domains whose connections have been obscured by our inherited disciplinary divisions: between science and what was becoming known as “culture,” the pursuit of knowledge and the transformative power of commerce, politically charged evocations of an emergent public sphere and worries about the turbulent impulses of popular culture, ideologies of polite sociability and the relentless contingencies of fashion. Lynn’s suggestion that ballooning, with its endless public venues, mass audiences, scientific claims and commercial opportunities, appearances in literary texts, and fashion spin-offs in everything from ladies’ hats to men’s shoe buckles, was “the popular science par excellence,” underscores just how thoroughly ballooning’s ubiquitous appeal circulated across these supposedly distinct social practices, discursive registers, and intellectual domains (Lynn, Popular 12). It also suggests the impact of endless barely remembered and sometimes only briefly successful cultural producers whose collective impact was a key element in the diffusion of new ideas. Robert Darnton’s insistence that we need to pay more attention to “the low-life of literature . . . who failed to make it to the top and fell back into Grub Street” applies just as strongly to historians’ growing interest in the “process of commodification and popularization” that science underwent in the eighteenth century “as more and more individuals sought to acquire some knowledge of scientific activities and as more and more people entered public debates on science,” a trend which manifested itself in a proliferation of “shops, fairs, private lecture halls, and other public locations [which] created spaces for scientific appropriation and purchase” (Literary 16; Lynn, Popular 2, 3). These developments were never unproblematic. For critics of Britain’s social order, the itinerant showmen who attracted crowds with their dramatic use of air pumps and electrical gadgets were intellectual imposters who draped themselves in the false dignity of scientific instruction in order to hide their lack of any rational purposefulness. “Electricity happens at present to be the puppet-show of the English,” Charles Moritz declared after his 1782 journey, “Who ever at all understands electricity, is sure of being noticed and successful” (88). But in recent years, historians of science such as Jan Golinski, Larry Stewart, and Lynn have offered a more generous version of the popularizing efforts of a group of “middling savants” who were dedicated to gaining an audience for these topics, and of the nature of the audience who flocked to see them (Lynn, Popular 3).[3] As Golinski has argued, these more recent approaches have been less focused on the Enlightenment as a grand narrative or distinct realm of ideas than on the many “little enlightenments” which characterized the transmission and reception of scientific ideas (Clark 27).

For Richard Holmes, whose book The Age of Wonder is adorned by a striking illustration of one of the Montgolfier brothers’ balloons, the ballooning craze was evidence of his broader argument that we are mistaken in assuming, as we have often done, that the Romantic period was characterized by a sense of the separation and even mutual animosity between the realms of literary and scientific thought. For Holmes, this period was animated by a “scientific revolution, which swept through Britain at the end of the eighteenth century,” an argument which runs directly against the grain of our own inherited characterizations of “Romanticism as a cultural force [which was] intensely hostile to science” (xv). Far from experiencing these as mutually exclusive and often hostile ways of seeing and being in the world, people living in this age viewed the world around them in ways that were nurtured by their interconnections. Most fundamentally, Holmes argues, they were united by a shared sense of “wonder” or almost reverential curiosity for the world around them (xvi).

These accounts of the late eighteenth century have been especially important because of the extent to which they anticipate the increasingly relational focus of our approaches to cultural history generally. In both our theoretical discussions and our critical practice, we have tended to emphasize the crucial formative influence of connections between various relations of cultural production and consumption (authors and readers, artists and viewers, performers and audiences), between the material realities and specific institutional contexts of these relations and the forms of symbolic capital which energized them, between the stubborn physical realities of books and other cultural objects and their endless signifying potential, between the scientific aspirations that we associate with Enlightenment thinkers and the bustling commercial world in which they were rooted, between aesthetic ideologies of creativity and more worldly forms of entrepreneurial ingenuity, and across different literary and visual forms. Our emphasis has been on both the highly mediated nature of these relations and on the two-way flow of this traffic of influences: the integral role of audiences in shaping ideas of cultural worth, not after the fact but as a crucial element in the productive process.

The risk in emphasizing the formative influence of these connections, however, is the tendency to reinscribe our accounts of them within a Whiggish narrative of social progress that implicitly valorizes the mutually nurturing force of these relations without adequately registering the influence of the anxieties that they also aroused. Descriptions of the “balloon influenza,” the “air balloon fever,” the “present rage,” the balloonomania,” and “the aerial phrenzy,” implied suspicions that the extremity of the public’s response reflected the unhealthy nature of modern nations’ vulnerability to excesses that were also part of commercial modernity (MP October 19, 1784; MP September 11, 1784; Seward 11; Walpole 25: 596; London Unmask’d 137). My argument is not with Holmes’ struggle to free us from the distortions of the historically anomalous disciplinary bounds that we have too often imposed on the past, especially in our understanding of the relations between what would become known as science and culture, or with his even more important hope that “with any luck we have not quite outgrown” this age of wonder, both of which are important and convincing interventions (xvi). But there is a danger that in making the case for this convergence we align ourselves with a progressivist model that underestimates the intensity of the anxieties which also attended these questions, and which saturated debates about both science and literature, as well as their intersections.

Ironically, given Holmes’ title, throughout the eighteenth century these tensions manifested themselves in strikingly acute ways in the word “wonder.” In Rambler No. 137, Samuel Johnson dismissed “wonder” as an “effect of ignorance. . . . Wonder is a pause of reason, a sudden cessation of the mental progress” (3: 72). For many eighteenth-century critics, the very word “wonder” seemed to smack of all that was most dubious about the commodification of knowledge. Pamphlets such as The Age of Wonders: or, a farther and particular Discriptton [sic] of the remarkable, and Fiery Appartion [sic] that was seen in the air, on Thursday in the Morning, being May the 11th 1710. Also the Figure of a Man in the Clouds with a drawn Sword; which pass’d from the North West over towards France, with reasonable Signification thereon (1710) played on an occult fascination with supernatural mysteries that flew in the face of any rational spirit of critical inquiry. Jonathan Swift reacted to plans to establish a national bank of Ireland in the wake of the South Sea crisis with a series of pamphlets including two entitled The Wonderful Wonder of Wonders. Being an Accurate Description of the Birth, Education, Manner of Living, Religion, Politicks, learning, &c. of Mine A—-se (1722) and The Wonder of all the Wonders, that ever the World Wondered (1722). The controversial overtones associated with an appeal to the public’s love of wonder gained an increasingly satirical edge in the years just prior to Lunardi’s flight when it became associated with the notorious scientific lecturer or (many critics insisted) charlatan, Gustavus Katterfelto, who had himself enjoyed brief but intense popularity in the early 1780s, whose seemingly endless newspapers ads promised, “WONDERS WONDERS, WONDERS AND WONDERS.”[4] In “The Grand Consultation,” George Canning mocked “That wonderful wonder, the great Katterfelto!”: “To see how great must be the rage,/ The wonders of this wond’rous age!” It was, as London Unmask’d put it, a “world of wonders” in which “novelty never ceases,” a “wonder-working age, in which invention seems to be on the rack to produce such curiosities as surpass whatever have gone before” (46, 135). It may well have been the age of wonder, but in a far less dignified or purposeful sense than Holmes’ argument implies. As Brewer and Roy Porter have argued, “one of the historical tasks of what we may loosely call the Enlightenment was to forge new sets of moral values, new models of man, to match and make sense of the opportunities and obligations, the delights and dangers, created by the brave new world of goods” (5). If ballooning was “the popular science par excellence,” it was also a vivid example of both the challenges and the potential responses that were a central part of this task (Lynn, Popular 12).

III

Whatever they thought of ballooning, no one doubted its impact. “Balloons occupy senators, philosophers, ladies, everybody,” Horace Walpole proclaimed (25: 449). “It is fashionable to speak of balloons,” the Morning Post agreed. “My Lord speaks of balloons – my lady speaks of balloons – Tommy the footman, and Betty the cook speak of balloons – yea, and balloons shall be spoke of. The sprightly Miss talks of nothing but inflammable air” (September 30, 1784). “The term balloon is not only in the mouth of every one, but all our world seems to be in the clouds,” declared a 1785 book titled London Unmask’d (137). Lunardi’s flight, on September 15, 1784, attracted an estimated 150,000 spectators, “the windows and roofs of the surrounding houses[,] scaffoldings of various forms and contrivances . . . crouded with well dressed people” (Lunardi, Account 26-27 [incorrectly numbered 34-35]). The Post reported that “St. Paul’s Cathedral took the advantage of Lunardi’s Balloon excursion, by raising the price, which used to be only twopence for going to the top, to two shillings, and both the galleries had a great number of spectators, many of whom in the stone gallery fell down the recesses and broke their shins, as they were walking round and gazing at the Balloon” (Sept. 23, 1784). The flights themselves were doubled by elaborate indoor displays, such as the spectacle that Betsy Sheridan witnessed when she visited the Pantheon to see Lunardi’s balloon during a trip to London in October 1784. There she saw Lunardi’s balloon “suspended to the Top of the Dome,” carrying “Lunardi, and his poor fellow travelers the Dog and Cat” who had accompanied him and “who still remained in the Gallery to receive the visits of the curious” (24). “The Pantheon seems to have become the fashionable lounging place for all the beauties in town,” the Post noted the same month as Sheridan’s visit. “The attractions are considerable: The magnificence of the building, the suspension of the Balloon and Gallery, and tho’ the last, yet seemingly not the least in admiration, Lunardi’s paying his respects to the chearful crowd for their friendly attention” (October 3, 1784).

The enthusiasm for ballooning had extended from science to show-business and in England, no one rivalled Lunardi, either in the extraordinary public response which his flights aroused, or, closer to the ground, in the skill with which he manipulated the narratives of these achievements in order to maintain the public’s interest. An article in the September 16th edition of the Morning Post (which Lunardi included in his swiftly published account of the flight), insisted that

every Englishman should feel an emulation to reward him; for uncertain as the good to be derived from such an excursion may be thought, yet it becomes the nobleness of our nature to encourage them. Discoveries beyond the reach of human comprehension at present, may by perseverance be accomplished. Emulation and industry are a debt which is due to posterity, and he who shrinks from innovation is not his country’s friend. (46)

A column the following day echoed this sentiment. “Wednesday the sublime, and bold flight of Lunardi, engrossed the whole of every conversation, not only in the metropolis, but its environs, at a considerable distance” (MP Sept. 17, 1784, p. 3). Weeks after the fight, Lunardi attended the theatre “with a party of Ladies, apparently vying with each other in shewing him attention and respect . . . the House in general hailed his appearance with a continued tumult of applause” (MP October 8, 1784).[5] His fame inspired everything from a new style of hat dubbed “the Lunardi” to a new shade of fabric named “Lunardi maroon,” but his greatest achievement may ultimately have been the seamlessness with which he fused these aspects of his career, as an aeronaut and an author who complemented his flights with rapidly published accounts, a self-styled Enlightenment hero advancing the boundaries of knowledge and a tireless self-promoter, a figure of ostentatious sensibility and a clever marketer, on display in his balloon in the Pantheon “paying his respects to the crowd.”

Nor was Lunardi reticent about the scale of the public’s interest. As his flight passed overhead, Lunardi noted in his An Account of the First Aërial Voyage in England, the King and Prime Minister interrupted a meeting with other “great officers of state” to watch the air balloon’s progress through telescopes (40). Their willingness to suspend the serious business of government in order to witness the most dramatic event of the day was understandable, Lunardi suggested. Elsewhere in London, a jury which had been reflecting on the case of “a criminal whom after the utmost allowance for some favourable circumstances, they must have condemned,” had “acquitted the criminal immediately” when the balloon appeared, in order that they might be free to watch (39). So great was the interest of the spectators, Lunardi recounted, “that the things I threw down were divided and preserved, as our people would relicks of the most celebrated saints” (39). Another publication recorded that a woman who recovered one of the dropped items only to have it “seized and torn to pieces by the populace,” declared “with streaming eyes and wringing hands . . . that the loss of her husband or one of her children would scarcely have given her more affliction” (Mr. Lunardi’s 10). The September 17th Morning Post reported that “Mrs. Saunders, widow of an upholsterer of that name, who formerly lived in Goodge-Street, was so terrified at the downfal of his oar, which she took for a human body, that she was suddenly taken ill, and in spite of all medical assistance, expired early yesterday morning.”[6] Lest Mrs. Saunders’ death be thought to tarnish his achievement, Lunardi hastened to add that he had been counseled by a Judge “not to be concerned at the involuntary loss I had occasioned; that I had certainly saved the life of a young man” (the criminal who had escaped almost certain conviction when the jury caught sight of the balloon) “who might possibly be reformed, and be to the public a compensation for the death of the lady” (39).

Lunardi’s advertisements for his display at the Pantheon, which appeared daily in leading newspapers such as the Morning Post and the Morning Chronicle alongside ads for competing flights and balloon-exhibits, books, hastily-assembled plays featuring ballooning references, and offers from balloon-makers (a favourite sideline of umbrella makers), exploited the full range of advertisers’ rhetorical strategies and special features.[7] Portraying himself as an Enlightenment man of feeling moved by the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings in an ad for his balloon exhibit at the Pantheon, Lunardi insisted that “he would think himself deficient in every sentiment of gratitude, were he not, from the effusion and overflow of his feelings, to pour forth his thanks in the warmest manner” by providing people with the opportunity to attend his display at the Pantheon (MP November 24, 1784). “Mr. Lunardi is peculiarly happy in having lately experienced, that the attachment of the Public to him is in unison with his feelings and particularity to this Nation,” another ad for his exhibit at the Pantheon proclaimed (MP May 5, 1785). This emotional reciprocity between an Enlightenment man of feeling and the nation which had embraced him, which found its clearest affirmation in the steady flow of paying customers to his exhibit, was a persistent theme. Insisting that “Mr. Lunardi has nothing more at heart than to gratify the public curiosity in the most ample and satisfactory manner, and that to disappoint the general expectation in the smallest particular, would be inexpressibly repugnant to the sincere and grateful feelings he entertains of their past favours,” yet another ad hastened to deny rumours of an imminent flight, and to announce that his exhibit at the Pantheon would remain open, having “spared no pains or cost to render it elegant and magnificent to the eye, and to blend in the numerous parts of his machinery, the ornamental with the useful” (MP March 26, 1785). Adopting a tone of patrician benevolence, a series of ads promised that he would not be distracted by the “encreasing degree of favour and encouragement” he was receiving “from a generous public” from forgetting “the feelings of humanity, but would as much as possible be instrumental to the relief of indigence and distress,” proof of which was his plan to open the Pantheon on the following Thursday evening “for the purpose of raising a charitable Fund, to be distributed among necessitous Persons, and Families whose situations have been properly certified and authenticated” (MP November 13, 1784).

However much he may have presented the exhibit at the Pantheon in terms which reinforced his scientific credentials, it was also distinguished by the pressures of fashionable sociability. Having stressed his gratitude “to a generous and intelligent people, to whom he is bound by obligations which he never can forget, to the latest hour of his life,” Lunardi announced that he would mark the imminent closure of his balloon exhibit at the Pantheon (in order to prepare for another flight) with a grand final night combining “his Exhibition” with

a ball on the said night, at which nothing shall be wanting to render it elegant, brilliant, and accommodating. In addition to the lights of the lustres, part of the Dome will be illuminated. The best Bands of Music that can be acquired for Minuets, Cotillons, and Country Dances, and every other particular that can tend to the entertainment or gratification of the company, shall be provided and attended to, under the management of two Gentlemen who have taken upon themselves to regulate the ceremony of the night with due and proper decorum. (MP November 24, 1784)

A masquerade at the Pantheon three months later was similarly “elegantly illuminated and embellished with the appendage of Lunardi’s balloon” (MP February 9, 1785). Yet another masquerade four months later combined decorations “representing the Grand Saloon of the Doge of Venice, decorated and ornamented in the most elegant taste” with “the balloon, [which] will likewise be suspended, with the Gallery and the whole of the apparatus” (MP June 6, 1785). Other ads promised the combined attraction of the balloon with “the musical child,” a prodigy who “will perform from Two o’Clock till Four, and though but Nine Years of Age, will take off several of our first Performers, and will Sing and Play at sight” (MP April 21, 1785).

Lunardi’s published descriptions of his various flights reinforced this orientation to the world of fashionable sociability by portraying himself as a man driven far more by his own unique brand of emotional intensity rather than by a spirit of rational inquiry. Even when “tottering on the brink of a total disappointment, I would not relinquish sensibility for the empire of the world!,” Lunardi insisted in his account of his frustrations when a subsequent flight was delayed: “Without sensibility, fame, riches, glory were empty sounds!” (Five 23). Adopting an intimate tone licensed by the epistolary format of his Account of the First Aërial Voyage in England, which was structured as a series of letters to his “Guardian” and “best and dearest friend” (1784), Lunardi dwelt upon “the extremes of elevation and dejection” which had marked his struggles to become Britain’s first aeronaut. “I am at this moment overwhelmed with anxiety, vexation and despair,” he confided after learning that a competitor, “a Frenchman, whose name was Moret,” was determined to beat him in his quest to perform the first flight in Britain. A conflict with the manager of the Lyceum, where he had been exhibiting the balloon, left him with a deep sense of “fatigue, agitation of mind, and that kind of shame which attends a breach of promise, however involuntary” (24).[8] In a letter written on the eve of his flight, his competitor Moret having failed and the obstacles which threatened his plan surmounted, Lunardi wrote: “Behold me, – I was going to say – but I should be extremely sorry you were to see me, exhausted with fatigue, anxiety and distress, at the eve of an undertaking that requires my being collected, cool, and easy in mind” (25).

Having triumphed over adversity, Lunardi’s comments on the voyage dwelt more on his emotional resurrection than on the flight itself: “All my affections were alive, in a manner not easily to be conceived; and you may be assured that the sentiment which seemed to me most congenial to that happy situation was gratitude and friendship. I will not refer to any softer passion” (34). The letters which covered his journey depicted him drinking a bottle of wine and eating chicken; caring for his fellow passengers, the cat and dog whom tens of thousands would view on display in the balloon in the Pantheon; and writing “dispatches from the clouds” (36), “pinning them to a napkin” and “commit[ting] them to the mild winds of the region, to be conveyed to my honoured friend and patron, Prince Caramancio” (34).[9] Not all of his missives would have descended so lightly. Having “emptied [his bottle of wine] to the health of my friends and benefactors in the lower world” (34), he “likewise threw down the plates, knives and forks, the little sand that remained, and [the] empty bottle, which took some time in disappearing. I now wrote the last of my dispatches from the clouds, which I fixed to a leathern belt, and sent towards the earth” (36).[10]

Mr. Lunardi’s Account of his Second Aerial Voyage from Liverpool, On Tuesday the 9th of August, 1785, offered an even more melodramatic version of this narrative of the trials and ultimate triumph of a man of feeling. Written as two letters, composed before and after his flight, Lunardi bared his soul about the hardship of having to wait for a change in the weather. Afflicted with “the most poignant Distress” at “the full Wretchedness of my Situation,” he waited “like a prisoner, who, expecting his Deliverance, anxiously counts the Moments till the happy Hour arrives, destin’d to restore him Nature’s first, best, Gift, Freedom!” (9). It was, he admitted, a desperate predicament, but perhaps one that all heroes must ultimately struggle with:

Sleep flies to the humble Cottage, and seals the Eye-Lids of the unambitious Peasant; on his Straw-Bed he slumbers happy, without a Care to break his Repose! what an enviable Condition! yet my Soul was never form’d to enjoy it: often have I said I will seek Peace in Retirement; but the glittering Phantom Glory, has darted across my Path, and I have pursued it as eagerly as ever! It is a false Light, an Ignis fatuus, that leads me into many a melancholy Situation: and yet perhaps To-morrow’s Dawn will see me following it with redoubled Ardor. (13)

Fortunately for Lunardi, his suffering was to be relieved. Improved weather conditions having enabled him to undertake his promised flight, his second letter depicted “such quick Transitions of Grief Rage, and Joy as have quite shook my Frame: I have been in a most horrid Situation! but, thank God, it is now over; and the Ladies and Gentlemen of Liverpool flatter me that I have given sufficient Proofs of Courage” (18). Refining on his previous self-image as a prisoner, Lunardi likened his reversal of fortune to “a Pleasure equal to that of a condemned malefactor who is reprieved at the Place of Execution!” (18). His Account of Five Aerial Voyages in Scotland, in a Series of Letters to his Guardian, Chevalier Gerardo Compagni (1786) repeated this now familiar narrative of abyssal despair, “surrounded as I am with distress and perplexities, and tottering on the brink of a total disappointment,” succeeded by ecstatic triumph (23). Far from attempting to maintain the rational poise that one might associate with a man of science, Lunardi emphasized his own “flighty” nature (10). If satirists revelled in the sexual overtones of Lunardi’s fame, this may have been in part an extension of Lunardi’s equally persistent description of himself as a man of extreme sensibility.

This penchant for emotional revelation, which dwelt on his inner turmoil as a melodramatic spectacle in its own right, was never easily separated from a more calculating sense of commercial opportunism. However noble the motivations driving Lunardi’s search for funding may have been, science, sensibility – his own as well as his spectators – and commerce had become closely entwined in his ongoing aeronautical career. Fusing a display of feelings (“the full Sensations of my Soul”) with entrepreneurial flare, Lunardi’s Account of his Second Aerial Voyage from Liverpool depicted himself drinking wine (though he was unable to eat, “so much was I affected by the Agitation of my Spirits a few moments before my ascension”) and sending off letters to those below (22). This time his letters were more carefully crafted “Proposals” entitled “A CARD from the SKIES,” a copy of which he included in his Account. In it, he

presents his best Compliments to his Terrestrial Friends; and begs leave to inform them, that, fired by Emulation and the love of Glory, and delighted with the Scenes upon which he now looks down, he wilt enlarge his BALLOON, and make an ærial Voyage, from Liverpool to the Isle of Man, provided the Ladies and Gentlemen will raise a Subscription sufficient to defray the expences of such a Journey, (150l.) before Friday next. (23)

For Lunardi, the commercial aspect of these endeavours was simply an English fact of life, “where the diffusion of wealth through the lowest ranks renders the whole nation the general patron of useful designs” (Account 7). His exhibits at the Lyceum and then the Pantheon could bring no disgrace to his endeavours since these would only be adding to “the innumerable exhibitions, which are always open in London, and which are the means of circulation, convenience, information and utility,” including the Royal Academy where “the first artists in the nation, under the immediate protection of the King, and incorporated into an academy, exhibit their pictures yearly” for an admission price of one shilling (Account 6).

Lunardi’s popularity, however, was as brief as it had been intense. By January 1786, The European Magazine could already refer to “the then fashionable rage for ballooning” two years earlier (13: 7). Lunardi, sensing that the winds of public interest had shifted, had already moved on. The July 1787 European noted Lunardi’s “experiment of his new invention for preserving persons from drowning. He launched himself in at Westminster Bridge, and passed down the river, through Black-friars, and also London bridge, at nearly the time of low-water” (1787: 12:77). Few people in the age were more adept at understanding and manipulating these connections between commerce, science, and fashionable sociability, but as the brevity of his fame also suggests, few careers better demonstrate the vexed nature of these shifting relations. For his critics, it was a happy irony that Lunardi should have made his first ascent from the Artillery Ground, adjacent to Bethlehem Hospital, or Bedlam as it was better known. “The figures of Phrenzy and Melancholy at [Bedlam’s] gate are celebrated throughout Europe,” Lunardi mused, “Which of these allegorical beings the people have assigned as my patron, I have not learned” (Account 27). The lesson of Britain’s commercial modernity, and of ballooning itself, was that it could be hard to distinguish.

Images

Figure 1: Love in a Balloon. Engraving, from the Rambler’s Magazine, 1784.

Figure 2: British Balloon, and D– [Devonshire] Arial Yacht. Engraving, by W. Dent, 1784.

Figure 3: The Political Parachute, A Coalition Experiment. Engraving, by W. Dent, 1785.

Figure 4: The Coalition Balloon, 1784. Engraving, published by E. Dachery, 1784.

Notes

[1] Rowlandson’s A Peep into Friar Bacon’s Study (1784), Colling’s The Golden Image that Nebuchadnezzar The King had set up (1784), and W. Humphrey’s Solomon in the Clouds!! (1784).

[2] See, for instance, prints such Elizabeth Henrietta Phelps’ Stock Exchange (1785) and Dent’s 1791 print, Bank Transfer, or, A New Way of Supporting Public Credit.

[3] See, for instance, Jan Golinski, Science as Public Culture: Chemistry and Enlightenment in Britain, 1760-1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992), Larry Stewart, The Rise of Public Science: Rhetoric, Technology, and Natural Philosophy in Newtonian Britain, 1660-1750 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992), and William Clark, Jan Golinksi, and Simon Schaffer, eds., The Sciences in Enlightened Europe (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999).

[4] For an account of Katterfelto’s career, see Barbara Benedict, Curiosity: A Cultural History of Early Modern Inquiry, 210-215. Benedict aligns Katterfelto with both performing animals and the rage for air ballooning as instances of the contested state of modern knowledge. See also Richard Altick, The Shows of London, 84-85; Fiona Haslem, From Hogarth to Rowlandson: Medicine in Art in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 202-214; Eric Jameson, The Natural History of Quackery; and Henry Sampson, A History of Advertising from the Earliest Times, 403-405.

[5] A series of at least twelve watercolour paintings by George Woodward, several of which depicted Lunardi’s various ascents, conveyed the visual magnificence as well as the heroic aura of the early flights. These can be viewed on-line at the Debryshire County Council website. My thanks to John Barrell for this source.

[6] Describing the loss of the oar (a common piece of equipment in early balloons) in his Account, Lunardi similarly reported that “a gentlewoman, mistaking the oar for my person, was so affected with my supposed destruction, that she died in a few minutes” (39).

[7] For advertising in this period, see John Strachan, Advertising and Satirical Culture in the Romantic Period. (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008); Nicholas Mason, Literary Advertising and the Shaping of British Romanticism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, forthcoming); and Paul Keen, Literature, Commerce, and the Spectacle of Modernity, 1750-1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2012), Chapter 6.

[8] Eager to negotiate a more profitable arrangement for himself after more than 20,000 people had flocked to see the balloon, the Lyceum’s manager had locked the balloon up until Lunardi agreed to pay a better share of the profits than they had previously arranged. Lunardi eventually recovered the balloon with the assistance of the police.

[9] An ACCOUNT of MR. CROSBIE’s ATTEMPT to CROSS the CHANNEL in a BALLOON from DUBLIN, JULY 19, 1785, offered a strikingly similar account of aerial travel: “My mind, that was hitherto voluptuously fed, made me inattentive to the cravings of my appetite, which at length grew rather pressing, and, with my pen in one hand, and part of a fowl in the other, I wrote as I enjoyed my delicious repast” (qtd. European 1785: 8: 133).

[10] Sending down communications was a favourite pastime of balloonists. In his account of a flight from London on 16 October, 1784, Jean-Pierre Blanchard recorded sending a letter “to a friend in London” by means of a pigeon which he took with him: “The bird flew away; and, after making some turns in the air, appeared to fly towards the capital, where indeed she arrived with my letter the same evening” (17).

Works Cited

The Age of Wonders: Or, a Farther and Particular Discriptton [Sic] of the Remarkable, and Fiery Appartion [Sic] That Was Seen in the Air, on Thursday May the 11th 1710. Also the Figure of a Man in the Clouds with a Drawn Sword; which pass’d from the North West over towards France, with reasonable Signification thereon. London: Printed by J. Read, 1710.

The Air Balloon, A New Song. London, 1785.

Bockett, Elias. All the Wonders of the World Out-Wonderd [sic]: In the Amazing and Incredible Prophecies of Ferdinando Albumazarides. London, 1722.

Byron, George Gordon, Lord. Don Juan. Austin: U of Texas P, 1957.

Canning, George. “The Grand Consultation.”

Clark, William, Jan Golinksi, and Simon Schaffer, eds. The Sciences in Enlightened Europe. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999.

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans Steven Rendall. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984.

Golinski, Jan. Science as Public Culture: Chemistry and Enlightenment in Britain, 1760-1820. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992.

Holmes, Richard. The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science. London: Harper Press, 2009.

Keen, Paul. “The ‘Balloonomania’: Science and Spectacle in 1780s England.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 39.4 (2006): 507-535.

—. Literature, Commerce, and the Spectacle of Modernity, 1750-1800. Cambridge UP, 2012.

London Unmask’d: Or the New Town Spy. Exhibiting a Striking Picture of the World as it Goes. London: William Allard, 1785.

Lunardi’s Grand Aerostatic Voyage Through the Air. London: Printed for J. Bew, J, Murray and Richardson and Urquhart, and R. Ryan, 1784.

Lunardi, Vincent. An Account of the First Aërial Voyage in England, in a series of Letters to his Guardian, Chevalier Gherardo Compagni. London: Printed for the author and sold at the Pantheon; also by the publisher, J. Bell; and at Mr. Molini’s, 1784.

—. An Account of Five Aerial Voyages in Scotland, in a Series of Letters to his Guardian, Chevalier Gerardo Compagni, Written Under the Impression of the Various Events that Affected the Undertaking. London: Printed for the authors and sold by J. Bell, Bookseller to his Royal Highness The Prince of Wales, and J. Creech, Edinburgh, 1786.

—. Mr. Lunardi’s Account of his Second Aerial Voyage from Liverpool, On Tuesday the 9th of August, 1785. London, 1785.

Lynn, Michael R. Popular Science and Public Opinion in Eighteenth-century France. Manchester, UK ; New York: Manchester UP, 2006.

—. The Sublime Invention: Ballooning in Europe, 1783-1820. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010.

Mason, Nicholas. Literary Advertising and the Shaping of British Romanticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, forthcoming.

Stewart, Larry. The Rise of Public Science: Rhetoric, Technology, and Natural Philosophy in Newtonian Britain, 1660-1750. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992.

Strachan, John. Advertising and Satirical Culture in the Romantic Period. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008.

Swift, Jonathan. The Wonderful Wonder of Wonders. Being an Accurate Description of the Birth, Education, Manner of Living, Religion, Politicks, learning, &c. of Mine A—-se. London, 1722.

—. The Wonder of all the Wonders, that ever the World Wondered. London, 1722.

Walpole, Horace. The Correspondence of Horace Walpole. Ed. W. S. Lewis. London: Oxford UP, 1961-83.

Longitude was a hot topic in eighteenth-century Britain. What we might perceive now as a niche, and perhaps rather uninteresting, navigational problem, was then crucial to finding a means of accurately measuring longitude at sea as Britain’s trade and naval aspirations expanded. Supported by very large award monies from the government, the search for a solution became a subject of national discussion, ridicule, and social relevance appearing in every conceivable type of source from newspapers and novels to prints and paintings.

Longitude was a hot topic in eighteenth-century Britain. What we might perceive now as a niche, and perhaps rather uninteresting, navigational problem, was then crucial to finding a means of accurately measuring longitude at sea as Britain’s trade and naval aspirations expanded. Supported by very large award monies from the government, the search for a solution became a subject of national discussion, ridicule, and social relevance appearing in every conceivable type of source from newspapers and novels to prints and paintings.