On Inauguration Day 2021, Americans welcomed the peaceful transition of power from the Trump era to the Biden years. After the Capitol insurgence on January 6, 2021, many Americans feared what might happen on this momentous occasion, and when we watched the inauguration we breathed a collective sigh of relief as Kamala Harris became the first woman (and importantly a woman of color) to become vice president and Joe Biden assumed his new role as president. We cried happy tears as we listened to Harris and Biden take their oaths, Amy Klobuchar speak excitedly about the day, a handful of singers give us fantastic renditions of patriotic classics, the first youth poet laureate Amanda Gordon read her riveting poem, clergymen lead national prayers, and, of course, our new president inspire us to hope for a unified American future despite the challenges this country faces in the days to come.

After the inauguration–perhaps even as early as it was taking place–we laughed together as we were given another gift: the Bernie Sanders sitting solo meme. As we watched politicians sit six feet apart and wear masks, gloves or mittens, fabulous coats, and hats, one stood out among the crowd: Sanders sitting in a relaxed pose with his arms and legs crossed, his taupe coat, and his brown, white, and black patterned mittens on. Something about that pose, something about the Bernie stare, just came alive on the internet. On January 20, 2021, the “bundled up” and “cozy and casual” Bernie Sanders inauguration meme went viral on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and many other online outlets. #BernieSanders was trending on Twitter, but it wasn’t for his politics. It was for the “first great meme of 2021,” though it is certainly not the first Sanders meme to show him wearing the coat. His “I am asking once again” campaign ad also became a meme.

Sanders sitting in his folding chair began to show up everywhere. As a Time magazine article confirms, the “Bernie Sanders in a Chair” meme hit Know Your Meme minutes after Biden was sworn into office, and transparent PNG files appeared on Twitter and elsewhere as quickly. A “Bernie Sanders in a Chair” SnapChat filter was even available. As a result, people took the “Bernie Sanders in a Chair” image and ran with it. Bernie showed up in famous art scenes, including Leonardo DaVinci’s Last Supper and Vincent Van Gogh’s Night Cafe. He showed up at a slew of sporting events, such as professional basketball games and kids’ soccer matches. He showed up in television shows, including The Golden Girls and F.R.I.E.N.D.S. He showed up holding Baby Yoda. He showed up in movies such as The Big Lebowski and Forrest Gump. Nick Sawhny created a website that uses Google Earth images and adds the Bernie Sanders meme to any location on the planet that has an address. Outsnapped created a website that let amateur meme makers create their own “Sit with Bernie Sanders” memes. If I continued to list all the places Sanders has appeared on the web, this essay would break the internet. However, there is one more place I have to mention.

Guess where else Bernie Sanders showed up: in Regency England. To be specific, he showed up in cinematic adaptations of Jane Austen’s Emma and Pride and Prejudice. What does it mean for Sanders to show up in Austen’s world in so many posts? It shows that Austen’s pop culture cache is as large as ever and that Austen is always relevant to current events. Connecting Austen to the United States’ inauguration is probably the last thing I would have thought to do–even as an obsessed Janeite–but when I saw the first Austen-Sanders meme, I was overjoyed. I began sharing images of Bernie not only sitting at the inauguration with Austen-themed captions, but also sitting in Jane’s drawing rooms, standing on a balcony, attending a picnic, and more. Although there are many Austen-Sanders mashups now in circulation, a few deserve recognition for what they can teach us about the conjunction of Austen’s world and today’s politics.

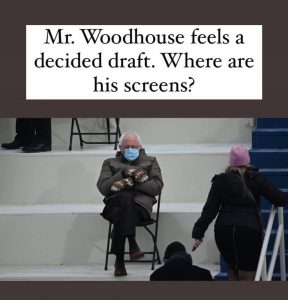

Fig. 1

Because January 20 was a cold day in Washington, D.C., and Sanders is an elderly gentleman, it just seemed natural for him to be associated with the aged Mr. Woodhouse. For instance, one of the first Austen-Sanders memes to go viral is this one (fig. 1), which reminds us of how much Mr. Woodhouse prefers staying inside during cold weather.

Fig. 2

Indeed, we can imagine Sanders as a Mr. Woodhouse who would prefer not be sitting in the cold but by a warm fire, so the internet decided to give us that, too (fig. 2). Here Sanders is Woodhouse adjacent–he does not sit within the screens, as Bill Nighy playing Emma’s father does, which makes him appear even grumpier. At least he gets to warm himself by the fire, though. These two images remind us that Bernie is practical, if nothing else. As he said on inauguration day with a chuckle to CBS News’s Gayle King: “You know, in Vermont. . .we know something about the cold, and we’re not so concerned about good fashion. We want to keep warm. And that’s what I did today.”

Fig. 3

A number of Woodhouse adjacent memes popped up, but in a warmer season: Sanders is wedged between Woodhouse and Miss Bates outside on a warm sunny day (fig. 3), and he sits inside next to Woodhouse waiting for Emma to unveil her masterful portrait of Harriet (fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

While we might have expected to see a Sanders-Woodhouse mashup, finding Sanders in Pride and Prejudice surprised me at first, until I began thinking about Bernie Sanders as a Mr. Bennet. When I saw the first Pride and Prejudice and Bernie mittens meme, I immediately shared it on my social media (fig. 5). Of course Bernie Sanders is a Mr. Bennet patiently sitting, waiting. What would please Mr. Bennet most: to have all of his daughters married off and out of the house so that he can get some peace–mostly from Mrs. Bennet, who desires her daughters to be married to the point of madness!

Fig. 6

Like the Emma memes that began with the image of Bernie sitting at the Capitol, the memes quickly transitioned to placing Sanders in Austen films. For instance, on January 21, Twitter famed account @TheRippedBodice unapologetically posted this one (fig. 6). Once again, we can imagine Bernie as a disgruntled Mr. Bennet waiting for his daughters to vacate the house so that he can have his rooms to himself. But Bernie Sanders showed up in other Pride and Prejudice places and in place of other figures.

Fig. 7

Bianca Hernandez-Knight, known as @bookhoarding on Twitter, created another Mr. Bennetesque Bernie meme–again focusing on the waiting (fig. 7). The women in Austen’s world are eager as Mr. Bennet to find a match, so why not place Mr. Bennet alongside them after a ball as they gaze longingly for something, anything to happen? Here Bernie may stand in for the absent Mr. Bennet once again.

Fig. 8

However, upon closer inspection, we find he takes the place of an important character–Lydia Bennet (fig. 8). What might it mean for Bernie to replace the outlandish Lydia, Mr. Bennet’s first daughter to wed, albeit under shady circumstances? While I don’t think Hernandez-Knight intended such a comparison, the image makes me think about Lydia’s absence as much as Bernie’s presence.

One thing these memes show us about Austen’s world is its attention to space. Even though Bernie (unwillingly) bumps Lydia off the balcony in the previous image (but keeps her feathers), the Austen-Sanders mashup mostly points to empty spaces in scenes, spaces that oftentimes denote an awkwardness of emotion.

Fig. 9

Take the scene wherein Mr. Collins proposes to Elizabeth Bennet as an example of not only tension, but also a kind of spectral Mr. Bennet presence. The Bernie meme has been called “a mood,” and it certainly is here (fig. 9). Even though Mr. Bennet is not in the room with his daughter during this scene in Austen’s book or in the adaptions, he is a part of Lizzie’s mind, and we find later that she cannot wait to talk to her father about how she cannot bear such a union. We know that Mr. Bennet agrees, and to put Bernie Sanders in this position is not simply funny but also reminiscent perhaps of his radical ideas concerning marrying for love. How progressive!

Fig. 10

But this is not the only meme in which Bernie replaces something. Naturally, the Instagram account @janeaustenmeme shared a bunch of Austen-Sanders mashups, but the one in which their Bernie sits next to Mr. Woodhouse in the 2020 Emma film when compared to the image I previously discussed demonstrates that Sanders took the place of a table (fig. 10). No longer sandwiched between Mr. Woodhouse and Miss Bates, our masked Bernie gets some breathing room, which could be dangerous in COVID times, and ends up balancing out the image, albeit marginally.

Another thing these images reveal is the desire for Austen fans to be a part of something culturally important and immediate–in this case not only the Austen meme world, but the celebration of Austen’s place in a viral online environment as well as the celebration of Sanders fandom and the inauguration itself. As Hernandez-Knight’s post indicates, there were Austen-Sanders memes before the ones she created (and she made a few); she had not seen one yet that places Sanders on the balcony, so why not make that one and share it? This is what Henry Jenkins would call participatory culture at its finest. The fans create the culture.

In the spirit of a good laugh, social media groups and individuals on their own accounts shared these memes with the acknowledgment that this Austen-Sanders combination is too funny. On Facebook Laughing with Lizzie writes, “These have been making me laugh all day Mr Woodhouse has a new companion!” Juliette Jones posted to the Jane Austen Universe Facebook the same cluster of images and prefaces them with a similar sentiment: “These have absolutely made my day .” Clearly these posts indicate that the Austen-Sanders mashups bring joy to fans and expand upon the joy that so many Americans, and people around the world, felt on January 20, 2021.

But why were similar posts with Austen-Sanders memes pulled from Jane Austen Fan Club’s Facebook page? A few posts appeared between January 20 and 21 showcasing the memes, but then members found on January 21 that the moderators deleted the posts. Fan club members were left to speculate as to why the posts were pulled: too funny? Absolutely not. Too political? Probably.

A lot of Facebook fan group pages have policies in which they prohibit anything remotely “political”–which could mean anything related to party politics, such as associative images with the Democratic Party or the inauguration of a president, or personal politics, including posts deemed objectionable to cis-het-white norms. It seems, then, that the Austen-Sanders meme posts were too political, even if they were funny and fans enjoyed them, and thus removed by the page’s moderators because either someone complained about them, or the moderators feared that someone would be offended by them. Even follow-up posts asking why the meme posts were pulled were removed the same day, but before they were, I can vouch through my own screenshots that many fans enjoyed the memes.

For instance, one fan said that they reminded her of her dad attending sporting events (bundled up and masked). Another fan said, “I loved them and wanted to share!” but sadly found them removed. Yet another fan proclaimed, “Sorry I missed them! Those Bernie memes are so funny.” I added my two cents: “Deleted? That’s a shame, as they show how relevant Austen is at this very moment.” Indeed, I understand why the moderators removed the posts, but I also thought about how many Austen fans seem to hold her up as an apolitical saint. Of course, those of us who have read Austen critically and in context know that plenty of scholars have shown how “political” Austen really was and how she tempered and veiled some of this politics in her writing but certainly did not eschew it.

That surely is another takeaway point from the Austen-Sanders meme going viral. While we might say they are too political for an Austen fan club page and that Austen has no place in twenty-first century American politics–and perhaps Sanders no place in Austen’s world–these two worlds complement each other and point to the fact that something as foreign to Austen’s time as a presidential inauguration and a politician’s image going viral can be productively mashed up to bring fans together. The joining of these two universes brought some added joy to an already momentous occasion that will surely go down in history as one of America’s most interesting inaugurations.

While the Austen-Sanders memes may not make it into the history books (but who knows?) and no one will likely associate Austen with the inauguration of Biden and Harris in years to come, those of us who watched the inauguration and scrolled through social media for the days to follow just might recall some funny “Bernie Sitting in a Chair” memes that reminded us of some beloved Austen characters and adaptations.

This summer more than 100 people, from readers to writers to scholars, will gather at the sixth-annual Jane Austen Summer Program to celebrate the bicentenary of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Attendees of “Northanger Abbey and Frankenstein: 200 Years of Horror” will have the opportunity to hear expert speakers and participate in discussion groups on the gothic-inspired novels. They also will partake in an English tea, dance at a Regency-style masquerade ball, attend Austen-inspired theatricals, and visit special exhibits tailored to the conference.

This summer more than 100 people, from readers to writers to scholars, will gather at the sixth-annual Jane Austen Summer Program to celebrate the bicentenary of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Attendees of “Northanger Abbey and Frankenstein: 200 Years of Horror” will have the opportunity to hear expert speakers and participate in discussion groups on the gothic-inspired novels. They also will partake in an English tea, dance at a Regency-style masquerade ball, attend Austen-inspired theatricals, and visit special exhibits tailored to the conference.

The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and The Jane Austen Society of North America—North Carolina

The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and The Jane Austen Society of North America—North Carolina The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen

The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen