This year marks the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of Waverley, Walter Scott’s novel about a naïve English soldier’s involvement in the Jacobite Uprising of 1745. Scott’s first novel and the nearly 30 works that constitute the Waverley Novels had a dramatic effect on the course of not only fiction, but history writing as well. Scott’s synthesis of historical subject matter, supernatural mystery, and romantic intrigue made his novels both enormously popular and critically acclaimed—no small feat considering the depths to which the genre’s reputation had sunk by the early nineteenth century, as Ina Ferris has shown.

Scott’s influence extended across Europe and into the United States. His works inspired paintings by (among many others) J.M.W. Turner, John Everett Millais, and Eugène Delacroix, as well as operas by Gaetano Donizetti and Arthur Sullivan. When Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery, he chose his new name based on a character from Scott’s poem The Lady of the Lake. In the Virginia town where I grew up, there is a street called Waverly [sic] Way, not far from Rokeby Farm Stables; I currently teach about 100 miles away from the town of Ivanhoe, VA. Along Central Park’s Literary Walk, a statue of Scott accompanies ones of Shakespeare and Robert Burns. Even his critics acknowledged his enormous influence: Mark Twain blamed the Civil War on Scott, “For it was he that created rank and caste [in the South], and also reverence for rank and caste, and pride and pleasure in them.” To illustrate his distaste, Twain named the wrecked steamboat in Huckleberry Finn the Walter Scott.

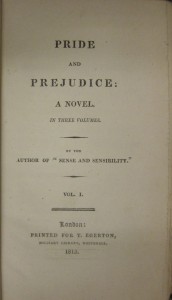

In short, Scott was enormously popular and influential as both a poet and a novelist—but few people today read his work for pleasure. [1] Go to a bookstore, and you’ll find maybe one or two of his novels, while his contemporary Jane Austen has rows and special displays devoted to her work, not to mention sequels and rewrites featuring zombies and vampires. Scott’s broader cultural presence has declined as well. Although Season 3 of Downton Abbey included a couple of references to his poetry, to my knowledge the BBC hasn’t adapted a Walter Scott novel since it produced Ivanhoe in 1982. The 1995 film Rob Roy, starring Liam Neeson and Jessica Lange, bears no relation to Scott’s novel of the same title. Perhaps the most recent popular film at all relevant to Scott is the 1993 comedy Groundhog Day, in which Andie MacDowell’s character scolds Bill Murray’s with lines from Lay of the Last Minstrel. (Murray, who plays a weatherman, expresses surprise when she tells him the author of the lines: “I just thought that was Willard Scott.”) Outraged politicians occasionally recite Scott’s lines from Marmion—“O, what a tangled web we weave, / When first we practise to deceive!”—but invariably attribute them to Shakespeare.

Why is Scott so forgotten? The scholar Ian Duncan explains that he “tell[s his] students: everybody loves Jane Austen. The real challenge is to say you love Walter Scott.” [2] And a challenge it can be, for a handful of reasons, including Scott’s convoluted plots, digressive narratives, and heavy use of dialect. But perhaps what deters most general readers from picking up a Scott novel is precisely why most readers of this website would be interested in doing so: the novels draw their dramatic intensity from specific historical events—and very often these events are rebellions, riots, invasions, and other crises of the eighteenth century.

It’s only a slight overstatement to say that the Waverley Novels can be understood as a fictional history of the eighteenth century, albeit from a distinctively Scottish perspective rather than the England-centric model to which most readers may be accustomed. Scott himself explained that his first three novels were meant “to illustrate the manners of Scotland at three different periods. Waverley embraced the age of our fathers, Guy Mannering that of our own youth, and the Antiquary refers to the last ten years of the eighteenth century.” Scott’s interest in the eighteenth century continued after this initial trilogy and he would return to Jacobite intrigue. His fourth novel, The Black Dwarf, involves James III’s failed effort to invade Britain in 1708; the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 lurks in the shadows of Rob Roy; and Redgauntlet concerns a fictional aborted Jacobite conspiracy of the 1760s (and, unlike his other novels, is told in the very eighteenth-century epistolary style). But Scott wasn’t exclusively a chronicler of various Jacobite failures. The historical event behind The Heart of Midlothian is the more obscure 1736 Porteous Riots in Edinburgh, and The Bride of Lammermoor depicts the contrasting consequences of the Act of Union for two Scottish families. (In the original edition of The Bride of Lammermoor, published in 1819, Scott set the action around the time of the Glorious Revolution.) “The Highland Widow” and “The Two Drovers,” stories from Chronicles of the Canongate, portray Scottish characters struggling to reconcile their beliefs and customs with their nation’s union with England; the third and longest tale, “The Surgeon’s Daughter,” revolves around characters’ attempts to find fortune in India in the late-1700s.

Scott’s eighteenth-century résumé expands if you follow the lead of many scholars and broaden the timeline to include the Restoration. Old Mortality concerns the Killing Time of the late 1600s, when Scottish Covenanters clashed with the government of Charles II; The Pirate is set in the Scottish islands of 1689 (and contains countless references to John Dryden and Restoration theater); and the Popish Plot is a major plot device in Peveril of the Peak. These settings and events afforded Scott opportunities to explore his favorite themes, including the contentious and often violent transition from one set of laws and traditions to another, whether it be the last gasps of Highland feudalism in Waverley or efforts to reform the Northern Isles in The Pirate.

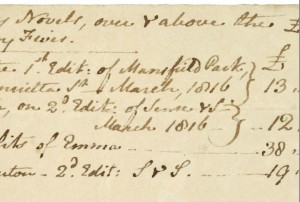

Although I have been emphasizing Scott’s interest in eighteenth-century subject matter, his interest in the period extends beyond that. He was informed by eighteenth-century thinkers, particularly Edmund Burke and Adam Smith, and devoted much of his career to the study of eighteenth-century poets and novelists. He published editions of John Dryden and Jonathan Swift, for which he also wrote biographies; and he was involved in an early attempt to canonize the British novel, contributing biographies of Daniel Defoe, Tobias Smollett, Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne, Horace Walpole, and others to Ballantyne’s Novelists’ Library.

I don’t expect Walter Scott’s novels to be re-imagined to include kilt-wearing vampires any time soon. But I am confident that readers interested in the eighteenth century would be drawn to Scott’s representations and interpretations of what he recognized as a tumultuous and exuberant age.

—————

Notes

[1] My point about Scott’s lack of an audience pertains to general readers; among scholars, he has been enjoying a revival for some time. Edinburgh University Press recently completed its new scholarly editions of the novels and has begun work on editions of the poems. This is in addition to the many scholarly books and articles about Scott’s work that have been published in the last two decades.

[2] Approaches to Teaching Scott’s Waverley Novels, 19.

June 16 to 19, 2016. Hosted by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and the Jane Austen Society of North America-North Carolina.

June 16 to 19, 2016. Hosted by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and the Jane Austen Society of North America-North Carolina.