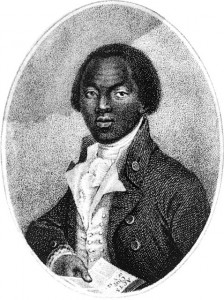

James Bruce by E. Topham. Etching, published 1775.

NPG D13789. National Portrait Gallery, UK. Used under Creative Commons Limited Non-Commercial License.

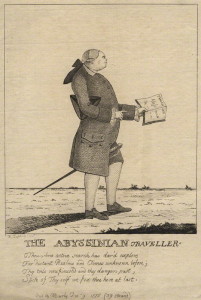

In 1773, James Bruce of Kinnaird returned to Europe after a decade of travel and study in North East Africa and Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia). Initially, the knowledge he brought back with him was favorably received by notable figures like the great naturalist the Comte de Buffon, Pope Clement XIV, King Louis XV, and Dr. Charles Burney, ethnomusicologist, composer, and father of author Frances Burney. But as time went on, the public began to grow suspicious of some of his stories, such as his claims that he had eaten lion meat with a tribe in North Africa or that Abyssinian soldiers cut steaks from the rumps of live cows, then stitched the cows up again and sent them out to pasture. As Bruce became a target of satirists and critics including Horace Walpole, John Wolcot, and Samuel Johnson, his standing in the European intellectual community began to slip. Walpole, for example, circulated a commonly cited anecdote in which, during a dinner party, one of the guests asked Bruce if he saw any musical instruments in Abyssinia. “Musical instruments,” said Bruce, and paused—“Yes I think I remember one lyre.” The dinner guest then leaned to his neighbor and whispered, “I am sure there is one less since he came out of the country.”[1]

Despite having been dubbed the “Abyssinian liar,” Bruce always stood by his word, and in 1790, he published a sprawling, five-volume narrative of his journey in an attempt to satisfy those whom he claimed, “absurdly endeavoured to oblige me to publish an account of those travels, which they affected at the same time to believe I had never performed.”[2] He titled the work the Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile because locating the source of the legendary river had been the primary purpose of Bruce’s journey. He always maintained that he was the first European to have achieved that goal, even though contemporary translations of Portuguese travel narratives indicated that Jesuit missionaries had made it there first, and even though subsequent explorers would point out that he had traveled only to the source of the Blue Nile (Lake Tana in present-day Ethiopia), not the source of the much longer White Nile (Lake Victoria in present-day Uganda). Nevertheless, the Travels was a bestseller, and the first printing sold out in 36 hours. His tales influenced literary figures like Frances Burney, who wrote about Bruce’s visits to her childhood home in her journals, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose dulcimer-playing “Abyssinian maid” in Kubla Khan was likely inspired by engravings of the court women who were enormously influential to Bruce’s knowledge of the region. Although it did little to repair his reputation at the time, his work contributed significantly to Western knowledge about Eastern Africa, and examining how the narrative sits on this paradoxical point between success and failure can tell us much about how knowledge and truth were culturally defined in the eighteenth century, during a time that laid the foundations for our own understanding of such concepts. In particular, Bruce’s situation highlights the way that heterogeneity of storytelling can come in tension with the singularity of truth, and how narratives that resist synthesis can reveal important information about what it means for something to be a true story.

Although the Nile was Bruce’s main objective, as a polyglot, diplomat, artist, and amateur scientist, he imagined advancing all areas of learning, and in many ways he succeeded. He recorded detailed descriptions of the people, architecture, and landscape from all across North East Africa. He mapped star patterns and recorded geographical coordinates for navigators and astronomers. The engravings and samples of plants and animals he collected were invaluable to antiquarians as well as scholars of botany, zoology, and medicine. He recorded a thorough history of Abyssinia’s monarchy, wrote about the Ethiopian Orthodox church, and brought the Codex Brucianus back with him—a gnostic manuscript that contained one of the first copies of the Book of Enoch circulated in Europe. He contributed to Dr. Burney’s History of Music. Perhaps his most significant contribution to Western scholarship is his documentation of Abyssinian court life at the beginning of Ethiopia’s “Era of the Princes.” He recounted extensive details about Emperor Tekle Haymanot II; about Məntəwwab, the commanding Dowager Empress of Ethiopia who had ruled as regent for several decades; about her clever and ambitious daughter Wäyzäro Aster; and about Aster’s extremely politically influential husband, the kingmaker Ras Mika’el Səḥul. Although Bruce’s tone is often characterized by a sense of European exceptionalism when he writes about the court, the power and intelligence of these individuals is evident, as is Bruce’s obvious respect and admiration for them—particularly the women, to whom he often refers as his closest friends and allies in the country.

But if Bruce contributed to all these advances in Western knowledge, and his narrative was so widely read, why did Britain’s reading public latch onto a few seemingly unbelievable details rather than the wealth of valuable information he brought back with him? After all, it was assumed that all travelers told some tall tales, yet Bruce seems to have received more than his share of scorn. The answer to this question illustrates the fact that eighteenth-century knowledge was extensively influenced by narrative techniques. Despite common assumptions that mid-to-late eighteenth-century natural philosophy automatically equated eyewitness accounts with factuality, whether or not such an account was considered trustworthy still depended a great deal on how its story was told. Samuel Johnson, for one, accused Bruce of not being a “distinct relator,” meaning that Bruce was often more interested in telling a raucous tale of heroic self-aggrandizement than in delivering objective geographical and ethnographical reports.[3] When Bruce did include specific details, they occasionally seemed too far-fetched to be possible, such as the aforementioned live steak incident, or his claims that Abyssinians ate their beef raw.

The skepticism over Bruce’s description of Abyssinians eating raw beef reveals a second reason why his narrative wasn’t always taken seriously: it didn’t square with people’s preconceived notions of what Abyssinia was like based on other representations of the region such as Johnson’s Rasselas, translations of Portuguese and French travel narratives, and even stories of Prester John’s land (a Christian country since the fourth century, Abyssinia had been considered a possible location of the legendary Christian kingdom amid the heathens since the Middle Ages). According to these portraits, Abyssinia was a civilized if foreign nation, not a place where the elite would eat uncooked flesh like “savages,” even though raw beef blended with oils and spices in fact was, and still is, an Ethiopian delicacy. In fact, the very inconsistency between details that eighteenth-century readers found barbarous and Bruce’s flattering descriptions of his friends in the Abyssinian court was a particular point of contention for one anonymous 1790 reviewer. He writes,

To a philosopher, the greatest inconsistency of all, is the discordant picture of Abyssinian manners. That nation is described as barbarous and ignorant in the greatest degree, as totally unacquainted with every country but their own; as liars and drunkards . . . yet, of Mr. Bruce’s Friends, some discover such discernment and force of mind, and some of the women display such delicacy of sentiment and elegance of behaviour, as would do honour to the most civilised nations.[4]

This perceived lack of coherence may have been a significant reason why Bruce’s Travels have largely been cursed to obscurity in spite of their initial popularity—seemingly contradictory stories exist side-by-side both inside the text in terms of Bruce’s descriptions and outside the text in terms of its reception history. As the above reviewer intimates, it is hard to get a handle on what the narrative—and thus what Abyssinia—is all about because our “philosophical” heritage trains us to equate inconsistency with falsehood. But this multiplicity is perhaps the most compelling reason for paying attention to the Travels now.

Bruce’s narrative is still the primary source of much of our knowledge today about east Africa during the mid-to-late eighteenth century. For one, understanding how such knowledge was produced can help us understand its limitations. Returning to the text, we are reminded that Bruce’s subject position as member of the eighteenth-century British gentry necessarily influenced the way he wrote about the non-European cultures he came in contact with. As such, proto-colonial discourse and British exceptionalism shaped much of what he saw and wrote about, and paying attention to these aspects reminds us that no knowledge is ever entirely neutral. Yet, the Travels are not reducible to these limitations—returning to the text can also open up how we think about how such knowledge was gathered. Take, for example, Bruce’s admitted debt to the women of the Abyssinian court for enabling his mobility both through the court and the kingdom itself. Bruce’s impressions of Abyssinia’s politics and even its geography may be as much a product of their worldviews than they are of his, and his text offers an opportunity to consider how such seemingly marginalized figures in the eighteenth century as African women may have in fact played a significant role in shaping Western knowledge. He similarly relied on his native guides and Gondar’s Greek and Muslim populations for much of his information not only about the city but also the surrounding countryside, not to mention the scholars, writers, and travelers—European, African, and Arabic—who paved the way for Bruce’s achievements long before he ever set foot on African soil.

In a 2009 TED talk, the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie spoke about the danger of the single story, about the incompleteness that results when we—like the anonymous author from the Monthly Review—seek homogeneity from representations of people and places rather than opening ourselves up to the many narratives that comprise both our pasts and our presents.[5] While Bruce and his paradoxical narrative may seem just a vestige of the past, from an era when the fields he helped advance—from geography and anthropology to theology and more—had not yet reached their full maturity, revisiting his story can help us reconsider how the production of European knowledge about the world may have in fact been a global affair. In spite of Bruce’s tendency to characterize himself as a solitary, intrepid traveler standing alone at the head of the Nile, from the Scottish traveler to his English critics, his Continental supporters, and his African friends, Bruce’s narratives bear the marks of the fact that modern knowledge has always been shaped by how multiple stories of the world are told and by the many people who have a hand in their telling.

Further Reading:

J.M. Reid, Traveller Extraordinary: The Life of James Bruce of Kinnaird. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1968: 310.

Charles Withers, “Travel and Trust in the Eighteenth Century.” L’invitation au Voyage: Studies in Honour of Peter France. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2000: 47-54.

Paul Hulton, F. Nigel Hepper, and Ib Friss, Luigi Balugani’s Drawings of African Plants: From the Collection Made by James Bruce of Kinnaird on his Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile 1767-1773. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1991.

Notes:

[1] As cited by Arthur A. Moorefield, “James Bruce: Ethnomusicologist or Abyssinian Lyre?” Journal of the American Musicological Society 28.3 (1975): 503.

[2] James Bruce, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile. Vol. 1. London, 1790: iii.

[3] James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson. London, 1827: 243.

[4] The Monthly Review, from May to August, Inclusive. Vol. 2. London, 1790: 188.

[5] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “The Danger of a Single Story.” TED Talks. Web. 29 Jan. 2015. <http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.>