Thomas Willis (1621-1675) thought there were two equal and opposite impulses at work when a person blushed, a modest retreat and an aggressive advance. In his book on mimicry, Dazzled and Deceived (2009), Peter Forbes has argued that all systems of natural mimicry, whether functioning as camouflage or warning, follow the same basic pattern of modest retreat and obtrusive truculence. Using the pictorial tools of analysis offered by William Hogarth, I discuss the relation of blushing to tattooing by comparing Sidney Parkinson‘s drawings of tattooed Maori heads (1773) first with Hogarth’s diagram of a blush, and finally with Titian’s Diana and Actaeon, hoping to suggest with a reasonable amount of plausibility that these all belong to the patterns of mimicry discussed by Forbes.

In one of the most testing passages of Hogarth’s The Analysis of Beauty (1753) he attempts a theory of three-dimensional viewing by asking us to suppose a hollow sphere. He invites the reader to imagine that the sphere is observed from two positions, from the outside where the surface appears convex, and from the inner where it will seem concave. By having an eye placed at some distance from the object and the other sitting at the centre of it we shall obtain, he promises, “the true and full idea of what is called the outlines of a figure.” If we habituate ourselves to this combination of a real and imagined position vis-a-vis the things we presently see, he promises we “will gradually arrive the knack of recalling them . . . when the objects themselves are not before [us],” so that not just spheres, cubes and pyramids but even the most subtle or irregular shapes will be as present to the fancy as if they were still in front of us (Hogarth 1810: 44-5). In staking this claim Hogarth flies in the face of one of the central tenets of empiricism, namely that an object and our impression or idea of it are entirely different. Thomas Reid was adamant about the “unphilosophical fiction of images in the brain” because it was axiomatic with him that “no sensation can resemble any external object” (Reid 1997: 121, 176). His conclusion concerning what he calls the “geometry of visibles” is precisely the opposite of Hogarth’s: “The geometrician, while he looks at his diagram, and demonstrates a proposition, hath a figure present to his eye, which is only a sign and representative of a tangible figure . . . and that these two figures of have different properties, so that what he demonstrates of the one, is not true of the other” (Reid 1997: 105-6). The imagined position of the eye at the centre of a scooped out egg, for example, is a figment adding nothing to our visual knowledge of the whole shape.

I labour this point because it is important for two reasons, first because it illustrates a significant difference between the sensationism of empiricists such as Hobbes, Locke, and Reid, and the Epicureanism of thinkers such as Walter Charleton and Thomas Stanley in the seventeenth century and David Hartley and Joseph Priestley in the eighteenth who believed, like Hogarth, that there was an immediate and intimate relation between the impression of a thing and the idea we have of it. Like Lucretius, their chief source of Epicurean materialism, these philosophers believed that there was no firewall protecting the mind or soul from the bombardment of the senses by light and sound. Indeed, Lucretius believed that every sensation arose from the print made by traces of the actual object, whether it was its film or effigy lodging in the eye, its effluvia entering the nose, or its reverberations penetrating the ear. The idea of a thing was therefore continuous with its material reality, it was not a sign or a symbol fashioned by the mind. Lucretius believed that sight, for instance, was something like a motion picture, with a succession of images emitted at great speed from the object striking the retina to give us not the illusion of shape, colour and motion but the immediate print of it (Lucretius 2006, 279-97; iv, ll. 26-268).

The second important reason for emphasising these rival epistemologies is that it gives us some sense of what is at stake when in the Analysis Hogarth arrives at the topic of light and colour, and begins to consider how they affect his three-dimensional approach to volume and depth. Pre-eminent in the artist’s palette, he says, is flesh-colour, which in portraiture moves between the extremes of black and white via the bluish tints around the temple and the rosy flush on healthy cheeks and lips. It is here that he tackles the nature of the blush, making an extraordinary attempt at a diagram with a black and white line drawing (Figure 1). Now there are three points I want make about this image. The first and simplest is that it attempts to circumvent the limitations of copperplate by treating it as if it were an acquatint, using shading to suggest variations in colour. Second, since there is no possibility of suggesting a blush on a woman’s cheek by means of cross-hatching without making it look like a bruise, Hogarth presents his blush as if it were a photographic negative, reversing the values of black and white so that a very faint thinning of the ink over the cheek can suggest the blush, while the whiteness of the lips stand for red. Thus he exploits (he says) the natural gullibility of the eye, an organ easily imposed upon and which, if it were not controlled, would show us things double and upside down (177). Third, he is adapting his technique of 3D inside/outside vision not for a sphere or an egg but for the face. He has told us that the skin is composed of two envelopes. There is the outer cuticle that is as transparent as isinglass, and “would show the fat, lean and all the blood-vessels, just as they lie under it” (187) if it were not for the inner cutis which, although it is opaque, is constituted of fibres whose coloured juices and meshes determine the individual complexion. In some young women, he says, “the texture is so fine . . . that they redden, or turn pale, on the least occasion” (188). Somehow Hogarth has managed in this diagram of a face to install an inner eye, capable of locating a lightening of the concave interior of uniform blood-red just in those places where, on the convex outside, red would be most on display against the surrounding white.

We call this a diagram, but it is not the sort of structure Reid is thinking of in his geometry of visibles, because instead of establishing a decisive difference between the thing itself and the formal outline that represents it, it is doing the opposite by insisting, perhaps rather awkwardly, on their coincidence. In some important respects this kind of diagrammatic experiment conforms to the insights about Hogarth’s art which John Bender began to analyse in his essay “Matters of Fact: Virtual Witnessing and the Public in Hogarth’s Narratives” when he talked about his facticity as a kind of staged realism. Far from schematising the relation between the spectator and the object, this staging (Bender argued) restores the possibility of a first encounter’s immediacy–perhaps beyond the zone of comfort, for he quotes Jean Rouquet to the effect that Hogarth’s vision “corresponds too closely to the objects it represents” (Bender 2012: 59; Rouquet 1746: 2). In his recent book The Culture of Diagram, Bender and his co-author Michael Marrinan study this proximity of vision to object by turning to the function of correlation that the non-perspectival organisation of diagram encourages. By dividing the sight-lines up between different points, the artist makes it possible for the viewer to assemble the different parts in a new configuration, and in effect to initiate a cognitive event (Bender and Marrinan 2010: 74). They single out Hogarth’s “Satire on False Perspective” as an exemplary lesson in diagrammatic correlation because of its overlay of `fractional visual fields’ that challenge the assumptions of one-point perspective by situating in the eye in a grid of rival viewing positions.

Such a challenge is not just practical or technical; it is also affective. Bender and Marrinan write, “Hogarth’s humour erupts at the juncture where the fixed, mathematically governed focus of classical linear perspective meets the curvature of physical eyes and their continuous scanning motion” (Bender and Marrinan 2010: 63). And what this humour produces they call “the effect of disequilibrium called amusement” (63). The affective element in games of visual disruption is much enhanced when the object is a blushing face, for the lines of it are easily understood as indices of temperament or emotion, lowered eyelids and the face turned away and so on, but when they are reinforced by a colour directly expressive of timidity, joy, anger, arousal, or shame then the impact is greater. And when that colour is perceived as it were from the inside rather than the out, disequilibrium makes room for affect. It is not too far-fetched then to venture the claim that Hogarth’s tiny outline of a blush turned inside out is in fact a diagram of emotion.

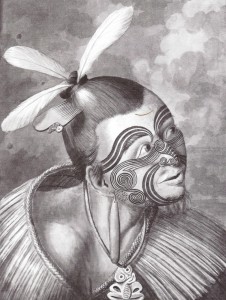

Figure 2: “Moko” Maori facial tatoo. Sidney Parkinson, from Hawkesworth’s Account of the Voyages… (1773).

Twenty years after Hogarth published the Analysis, the British public was treated to further examples of this diagrammatic art in the shape of Sidney Parkinson’s two portraits of Maori from the Poverty Bay region of Aotearoa/New Zealand’s North Island, published in John Hawkesworth‘s An Account of the Voyages and Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere (1773). These show two very different types of facial tattoo. One is called moko (Figure 2), composed of whorls and scrolls typical of Maori carving on the finials of meeting houses and the stern-posts of canoes, often framing an ancestral figure or poupou; the other is called puhoro (Figure 3), which bears a remarkable resemblance to Hogarth’s diagram (Figure 1) . It is a much freer design of volutes and lines derived from the decorative art on the rafters of buildings, known as kowhaiwhai. The history of puhoro as a facial tattoo is difficult to tell, since by the early 19th century it seems to have been reserved exclusively for thigh ornament; whereas moko very soon after contact became the exclusive design for the face. Very quickly one observes that moko is an ornament inscribed on the surface, like ink on paper and not, like puhoro, making its way through the ink in the manner of Hogarth’s blush. Done by chiselling the charred black of candlenut into the subcutanenous layer of the skin, moko was a visual challenge intended to emphasise the contours and furrows of the countenance, particularly those that come into play in grimaces of aggression and fury. It is also worthwhile pointing out that a moko was unique to each individual and was commonly supposed to reveal a shorthand genealogy as well as the identity of the owner, rather like the heraldic devices on the shields of knights at arms. Many of the chiefs who signed the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 did it with their moko. So as well as the emotions incident to the close encounters of battle, this kind of tattoo was the cicatrice of an exceedingly painful set of incisions in the flesh, the perpetual demonstration of a fearful glory, or mana, connecting each hero to his ancestors by means of a design carved into his memory as well as his skin.

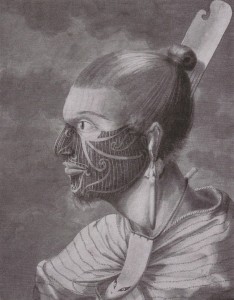

Figure 3: “Puhoro” Maori facial tattoo. Sidney Parkinson, from Hawkesworth’s Account of the Voyages… (1773).

Puhoro on the other hand, being seen in negative with white lines defined by a shaded ground, seems much more discreet. If moko is the sublime, a powerful emission of energy outwards, associating the surface of the skin with the external ornaments of buildings and canoes, puhoro is the beautiful, belonging to the inside of houses, and in some sense the interior of persons. What the nature of this interior might be is best approached via the idea of tattoo as an affective diagram. To early European visitors moko seemed not hard to work out: it was designed to disturb the symmetry of the face, fixing it in a glare that would be frightful in war–at least this was the opinion of Joseph Banks on Cook‘s first voyage, and of J.R. Forster on his second. Neither of them however was able to view the phenomenon dispassionately: Banks found himself revolted by faces rendered “enormously ugly,” but at the same time he was fascinated by “the immence Elegance and Justness of the figures in which it is form’d” (Banks 1962: 2.213-4). It prompted Forster to remember the other side of the affective spectrum, for these carved masks of rage reminded him of the scars left in the foreheads of Polynesian women who cut themselves in order to exhibit in the blood streaming down their faces the reality of their grief for dead relatives or departing friends (Forster 1996: 347). The most extensive analysis of aggressive disruptions of symmetry in Polynesian art is Nicholas Thomas’s essay “Kiss the Baby Goodbye,” where he explores the implications of objects, whether tattooed, carved or painted, which come too close to their viewers and throw them off guard. “Like erotica, these artifacts have effects which are indexed in a viewer’s body, which precede and supersede deliberate reading . . . unstable patterns would disempower people and empower others” (Thomas 1995: 101, 99). So it is mobile and haptic; it means to constitute a physical event for whoever looks at it. Thomas suggests that the bulges and bends of Sepik and Asmat shields, accentuated by the designs carved and painted on them, exhibit a palpable instability and a pulsing energy–energy analogous, I’d suggest, to the humour that erupts in Hogarth’s “Satire on Perspective,” except that the latter is a diagram of amusement, and these are diagrams of dismay.

Of Parkinson’s tattooed faces, Bernard Smith remarked that they showed no emotion (Smith 1985-87: 1.34-43), and there are perhaps two reasons for that. The first is that in drawing a facial tattoo a conflict inevitably occurs between the outline of the face and the structure of the design, since that was what was intended by it. The second is that the conflict is palpable, an effect of the proximity of face to viewer that floods the shared space with energy: the face is not showing emotion in the sense of representing it, it is causing it to happen. But how exactly does it do it? Is it simply by the hydraulics of power, sucking it out of the viewer and storing it in the object being viewed? Banks is certainly repelled by tattoos, but he is also attracted by them; and in the process of a visual dialectics Bronwen Douglas calls countersigning (Douglas 2005, 51) it is evident that the energy transmitted by a tattoo, lodged in the body when the tattoo was made, is expelled and then returned to it via the body it affects, whether the impulse is provided by revulsion or fascination. In this respect the link between moko and the aesthetics of the sublime grows stronger, for Longinus noted not only that it struck the auditors or viewers like a blow, leaving them prostrate and in the condition Kant calls Hemmung, but that it was soon followed by a surge of power he called Ergiessung, and Longinus “transport,” when the projected force is rebounded upon the projector, and the victim feels suddenly like the aggressor (Longinus 1739: 14). Like any challenge, then, moko is an incitement to fight; it is not meant to terminate in the paralysis of the enemy. It is both the menace of violence and the expectation of it, a weapon and a shield, the trace of blood spilt and the promise of more to flow.

Blood has a milder but still dynamic function in puhoro, where force is not projected so much as apprehended. As if positioned in a blood-red interior, the inner eye encounters another eye outside that may be wishing to see more than it should. Its lattice of white perpendicular white lines and transverse volutes, showing up against a darkened or blushing skin, acts like a fan or jalousie to obstruct one option of the viewer and to encourage another. It obstructs whatever advantage might have accrued from seeing a face reacting to the surprise of being seen, and it encourages the intrusive eye to enjoy its own curvature, and to indulge the scanning motion that is its natural rhythm. According to Nicholas Thomas kowhaiwhai above all Maori designs figures the motion of things and amuses the eye by inviting it to roll from one optical complexity to another (Thomas 1995: 103-4).

Figure 5: Gunboat HMS Kildangan in dazzle camouflage, 1918. Imperial War Museum, London. Printed in Forbes, Dazzled and Deceived.

If tattooing owed anything to forms of mimicry in the natural world, then moko would belong to those dazzle patterns of snakes that advertise their venom with loud bands of yellow and red (Figure 4), a technique adapted during the second world war to confuse measurements of the heading and speed of warships while proclaiming very distinctly their deadliness (Figure 5). Puhoro on the other hand would belong with the arts of camouflage that make nakedness look like something else, such as those butterflies that simulate leaves, and spiders that get by in life by pretending to be bird-droppings (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Photo by Flickr user ToddinNantou.

Figure 7: Titian, ‘Diana and Actaeon’, 1556-59 © The National Gallery London / The National Galleries of Scotland

The swirl of energy around the variety of positions charted by adaptive mimicry, what Roger Caillois calls “sculpture photography” (Forbes 2009: 135) and we have been calling 3D affective diagrams, provides the drama one of Titian’s greatest pictures, Diana and Actaeon (Figure 7), painted in the mid-sixteenth century and recently the inspiration of a new three-part ballet called Metamorphosis: Titian 2012, first performed in London in at the Royal Opera House in the summer of 2012. While hunting in the forest Actaeon stumbles on Diana’s pool, and sees her naked; the goddess is outraged, and is about to fling water in his face that will turn him into his own quarry, a deer. Of the many artists attracted to this scene, Titian is one of the few to have shown Diana blushing, and almost I think the only one not to show Actaeon with horns growing out of his head. We can see that her blush organises what we might call the diagram of the whole picture, for with the exception of Diana, her black companion and the nymph peering from behind the arch, all the other faces are unlit or half-shaded, as if each is ashamed at having caused the figurehead of chastity to be caught in her bare skin by a man. Whatever erotic charge might have been in store for Actaeon has backfired, and so we find him engaged in two contrary motions at once, coming forward to look and going back to hide. Diana herself is engaged in the same awkward manoeuvre, lifting a veil and an arm to conceal her face while at the same time seeming to wind herself up for the throwing of water. So at either side of the composition a pulse of inward/outward movements is in play that renders the two main figures quite awkward, for Actaeon’s feet seem to be going in a different direction from his torso and his head, contributing to a total effect of what might have been wonder in a painting by Poussin but here looks like extreme uncertainty. The swivelling of Diana’s body is not at all sinuous, for the leg being dried by her attendant throws it out of balance, while equivocal position of her upper body makes her head look as if it were borrowed from a smaller person. Her well-lit blushing face, shadowed by the black one alongside, condenses the alternatives set out in the picture at large between the aggressive dazzle of red laid on white, and the recessive possibilities of shade. Here white emerges from the dark ground of the black woman’s face as if in mimicry of a blush–just like Hogarth’s diagram and Parkinson’s rendition of puhoro.

The woman staring from behind the column quadrates the picture, for while at either side the drama of attraction and repulsion is being played out, there is another occurring on the transverse axis that connects the peering half-hidden nymph on the inside to the spectator on the outside. Her gaze is directed diagonally at Actaeon suggesting that ours is directed at parallel angle towards Diana, implicating us in Actaeon’s erotic shock. At an exhibition at the National Gallery mounted to coincide with the performance of the ballet Metamorphosis, this picture was hung by the artist Mark Wallinger near a side room where visitors could look through a peephole into a cabinet where a real naked woman was taking a bath. Asked what he was aiming at, Wallinger replied, `to make the viewer a little uncomfortable.’ Let me end with a quotation of Thomas Willis, a close affiliate of those Epicureans I began by invoking, on the dual pulse of the blush

Concerning this Passion [of shame], ‘tis observable that when the Corporeall Soul being abashed, is enforced to repress its Compass, she notwithstanding being desirous, as it were to hide this Affection, drives forth outwardly the Blood, and stirs up a redness in the Cheeks. (Willis 1683, 54).

He suggests the blush veils the shame, but insofar as it is directed outwards against a likely witness, it belongs to what he calls the power of dilation or emanation, when the soul “erects and stretches out it self beyond measure’ in its desire to `enlarge the Sphear of [its] Irradiation” (Willis 1683: 45). The vital energy that animates the blush of anger is mixed up with the blood that signals the contraction of the soul’s compass. One blush is looking to camouflage itself from an intrusive gaze, the other to dazzle the eye that has presumed to look where it shouldn’t; but the energy they draw upon is the same. In Diana and Actaeon, in Hogarth’s diagram from The Country Dance, and in moko and puhoro tattoos, the same double pulse of energy is in play. In all three the action of looking and the response to being seen are distributed in three dimensions, so that even the viewer’s eye is implicated in a set of visual contingencies that Lucretius would have called an event.

********

References

- Joseph Banks 1962, The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks, ed. J.C. Beaglehole, 2 vols., Sydney: Public Library of New South Wales and Angus and Robertson.

- John Bender 2012, `Matters of Fact: Virtual Witnessing and the Public in Hogarth’s Narratives,’ in Ends of Enlightenment, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- John Bender and Michael Marrinan 2010, The Culture of Diagram, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bronwen Douglas 2005, “‘Cureous Figures,’ European Voyagers and Tatau/Tattoo in Polynesia, 1595-1800,” in Thomas, Cole, and Douglas eds., Tattoo.

- Peter Forbes 2009, Dazzled and Deceived, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- John Hawkesworth ed. 1773, An Account of the Voyages and Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, 3 vols., London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

- William Hogarth 1810, Analysis of Beauty, London: Samuel Bagster

- Longinus 1739, On the Sublime, trans. William Smith, London: J. Watts.

- Lucretius (Titus Lucretius Carus) 2006, On the Nature of Things, trans. W.H.D. Rouse, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Thomas Reid 1997, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, ed. Derek R. Brookes, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Bernard Smith and Ruediger Joppien 1985-88, Art of Captain Cook’s Voyages, 3 vols., New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for British Art.

- Nicholas Thomas 1995, `Kiss the Baby Goodbye: Kowhaiwhai and Aesthetics in Aotearoa New Zealand,’ Critical Inquiry 22 (Autumn 1995), 90-121.

- Nicholas Thomas, Anna Cole, and Bronwen Douglas eds. 2005, Tattoo: Bodies, Art and Exchange in the Pacific and the West, London: Reaktion.

- Thomas Willis 1683, Two Discourses concerning the Soul of Brutes, trans. Sam. Pordage, London: Thomas Dring.