The Letters of Hannah More: A Digital Edition brings together for the first time the fascinating letters written by the celebrated playwright, poet, philanthropist, moralist, and educationalist Hannah More (1745-1833).

The Letters of Hannah More: A Digital Edition brings together for the first time the fascinating letters written by the celebrated playwright, poet, philanthropist, moralist, and educationalist Hannah More (1745-1833).

More was one of the most important voices of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. At the heart of a complex and extensive network of politicians, bishops, writers, and evangelical Christians, which included figures such as William Wilberforce, Samuel Johnson, and Elizabeth Montagu, More sought to redefine and reshape the social and moral values of the age.

Though More’s fame and influence were considerable throughout her fifty-year literary career, she has remained a peripheral figure in later assessments of the literary culture of the period. In part this is because some of her views are unappealing to modern tastes (she argued strongly against women becoming more involved in political life, for instance, and she was fiercely opposed to Catholic emancipation), but it is also because she has acquired a reputation for dour, dreary earnest religiosity. That her evangelical Christian beliefs were central to More’s life and works is undeniable, but she was also playful and light-hearted, and she especially delighted in the company of children. More’s cheerless reputation developed after the publication in 1834 – just a year after her death – of William Roberts’s four-volume edition, Memoirs of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More, in which More’s cheerful and teasing voice was deliberately and ‘primly’ edited out. So badly did Roberts misrepresent More that her goddaughter Marianne Thornton begged correspondents not to “judge of Hannah More by anything […] that Roberts tells you she said or did.”

To her friends and family, the publication of More’s letters was inevitable. In 1813, William Weller Pepys urged her to compose her letters so that “the subjects, though familiar, should be always interesting.” He acknowledged that writing for publication ran the risk of producing mannered and contrived letters “yet I would not have you totally lose sight of the possibility of such a thing taking place” (Roberts, III, 380). Prior to her death in 1819, Patty More undertook the initial editorial groundwork by collecting together relevant letters and papers (without her sister’s knowledge). The task was continued by Mary and Margaret Roberts, to whom Patty had entrusted the papers and whom More later appointed her literary executors, who worked on arranging, copying, and dating the letters, “the most troublesome part of a posthumous concern,” More observed from a distance (Huntington Library, HM 30620). The Roberts sisters also approached their brother, William, a lawyer and journalist, about taking on the role of More’s official biographer and editor. The resulting four-volume Memoirs of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More was published in 1834.

More had some experience of the administration of a literary estate. In early 1781, she assisted Eva Maria Garrick, the widow of David Garrick, More’s theatrical mentor of the late 1770s, to arrange and dispose of his letters. Among them she discovered her own letters but, observant of protocols for such matters, considered it “a breach of trust to take them till they are all finally disposed of” (Roberts, I, 193). Garrick’s carefully ordered papers, however, contrasts with the disorderliness of More’s own extensive archive which fell increasingly into disarray as her mental faculties diminished in old age: Mary Roberts worried how More, who was “no longer capable of exercising the same care & caution as formerly,” suffered private letters to “lie scattered on her Table” (British Library, Eg. 1965, f. 100).

The size and content of More’s archive inevitably fluctuated over the years. The majority of the letters that she wrote, of course, ended up in the collections of their recipients. Some groups of letters, however, found their way back into More’s archive, such as her letters to Horace Walpole and her early letters to William Weller Pepys, although what survives today cannot reflect the extent of the original accumulations. Nor were all of More’s letters considered worthy of long term retention. William Roberts observed that when More was afflicted by a pleuralic fever, “The letters which were received by her sisters . . . amounted to some hundreds. They were destroyed; but had they been preserved, their unvarying topic would have excluded the variety to which letters owe their interest” (Roberts, III, 244). More herself, concerned for her posthumous reputation, was not averse to destroying letters: she burnt nearly two hundred letters sent to her by Clapham Sect friend, Henry Thornton, and requested that Marianne Thornton destroy a series of her own letters after her death (Huntington Library, MY 669 and MY 716). Consequently, the letters that survive in manuscript and print must represent only a fraction of More’s epistolary output.

Although affecting disinterest in her biography while alive, More was concerned to assist in the reconstitution of her archive following her death: a provision in her will, which requested that all the friends with whom she corresponded hand over her letters or copies of them to her literary executors, was designed precisely to facilitate the posthumous editing of her letters. At least one friend, Marianne Thornton, refused to turn over her letters to Roberts believing them unfit for publication. Other friends, however, were more cooperative, such as John Scandrett Harford and Lady Olivia Sparrow. To the latter, Mary Roberts proposed a reciprocal exchange of letters and assured her that any “private or confidential matters” would be expunged before publication (British Library, Eg. 1865, fol. 100). She also outlined the broad editorial methodology that had been adopted: as many as possible of More’s letters to her “intimate correspondents” would be recalled at the earliest opportunity in order to allow sufficient time for their appraisal, and from each parcel a few of “most interesting & worthy of insertion” would be selected for the memoir. A group of More’s letters to Lady Olivia Sparrow (with a few to her daughter, Millicent), was sold by her grandson, Lord Robert Montagu, to the British Library in 1865, and a selection of these form the basis for this pilot project. Five letters from More to Lady Olivia Sparrow are preserved in what remains of her original archive (William Andrews Clark Memorial Library), and the project team will in due course establish the extent to which these particular manuscripts relate to the letters that Roberts selected for publication. Today More’s 1,800 letters are scattered across some ninety repositories in Britain and North America with at least two groups of letters remain in private ownership.

The publication of More’s letters for the first time in a reliable and scholarly edition (which will also be fully searchable) will bring back together, for the first time since their dispersal in the nineteenth century, what remains of More’s epistolary output. Doing this will enable a much-needed reassessment of her significance by making explicit the extent to which More was embedded within, and exercised great influence over, the major cultural, political and social networks of her era. It will also make visible for the first time the larger patterns of More’s letter-writing activities: already, visualizations of the data gathered so far offers insights into the way More’s letter writing changed over time; how her relationships with her closest correspondents shifted; to whom she wrote most often. The rhythms of eighteenth-century life can also be seen to exert an influence over More’s letter-writing, with More writing far fewer letters whilst the fashionable were in London. A staunch defender of Sabbath-keeping, More unsurprisingly wrote very few letters on Sundays, but she wrote more than might be expected of an avowedly strict Christian woman.

The edition of More’s letters is currently under construction: a small collection (to Lady Olivia Sparrow) is available, and this will be added to gradually over the next six months. It is hoped that all of More’s surviving letters will be available within the next four years.

The project is a collaboration between scholars from the UK, the US and Canada.

Project Leader: Dr. Kerri Andrews, University of Strathclyde

Technical Adviser: Professor Laura Mandell, Texas A&M

Modern Humanities Research Associate: Dr. Sarah Crofton, University of Strathclyde

Advisory Board: Dr. Nicholas D. Smith, Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Dr. Sue Edney, University of Bristol; Dr. Anne Stott, Independent Scholar; Dr. Anne Milne, University of Toronto; Dr. Dahlia Porter, University of North Texas

The project has been supported by funding from the Carnegie Trust, the MHRA, and the University of Strathclyde.

The Marquis d’Argens (1704-1772) is mainly famous for a book he did not write, Thérèse Philosophe. That is a great pity, as the books he did actually write are far more fascinating and entertaining than that unfortunate misattribution. D’Argens was a sceptic, a thorn in the side of the Catholic Church, whose books were denounced by the Inquisition; one of them, La Philosophie du Bon-Sens, was burnt in Paris. He was also a close friend of Voltaire, and he belonged to the generation that is often overshadowed by that towering genius. Voltaire greatly admired d’Argens’ Lettres Juives, an epistolary work in which he wrote from the point of view of learned Jews discussing and often mocking the beliefs and customs of the Christian world. The book manages to combine the subtly intellectual with the entertaining in a remarkable manner. As a novelist, philosopher, translator, classical scholar, and art critic, d’Argens’ works are so divers that he is difficult to categorize; he was notorious in his own time for his scandalous Memoirs, in which he recalled his youth and love affairs in Paris and Italy in the 1720s and 30s. A wild elopement, a brief army career, and an ongoing battle with his father, who wanted him to study law, provided the main subject-matter. Those who read these Memoirs sometimes formed the opinion that he was merely a libertine and a lightweight, but that is not borne out by a careful study of his work. The mind that emerges from them is deeply reflective, and the philosopher is always apparent in the novels, just as the imagination of a novelist lurks in his works on philosophy.

The Marquis d’Argens (1704-1772) is mainly famous for a book he did not write, Thérèse Philosophe. That is a great pity, as the books he did actually write are far more fascinating and entertaining than that unfortunate misattribution. D’Argens was a sceptic, a thorn in the side of the Catholic Church, whose books were denounced by the Inquisition; one of them, La Philosophie du Bon-Sens, was burnt in Paris. He was also a close friend of Voltaire, and he belonged to the generation that is often overshadowed by that towering genius. Voltaire greatly admired d’Argens’ Lettres Juives, an epistolary work in which he wrote from the point of view of learned Jews discussing and often mocking the beliefs and customs of the Christian world. The book manages to combine the subtly intellectual with the entertaining in a remarkable manner. As a novelist, philosopher, translator, classical scholar, and art critic, d’Argens’ works are so divers that he is difficult to categorize; he was notorious in his own time for his scandalous Memoirs, in which he recalled his youth and love affairs in Paris and Italy in the 1720s and 30s. A wild elopement, a brief army career, and an ongoing battle with his father, who wanted him to study law, provided the main subject-matter. Those who read these Memoirs sometimes formed the opinion that he was merely a libertine and a lightweight, but that is not borne out by a careful study of his work. The mind that emerges from them is deeply reflective, and the philosopher is always apparent in the novels, just as the imagination of a novelist lurks in his works on philosophy.

As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as

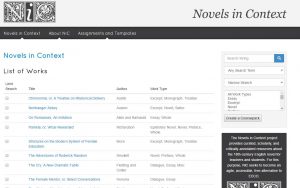

As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as  Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.

Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.  Novels in Context

Novels in Context The Letters of Hannah More: A Digital Edition

The Letters of Hannah More: A Digital Edition ‘

‘