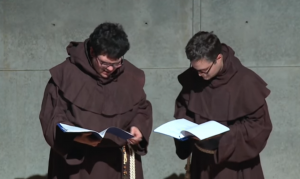

Charlie Gillespie and Rev. Justin Crisp playing Friars Benedict and Martin in Walpole’s play The Mysterious Mother. May 2, 2018.

Playing Friars Benedict and Martin was something of a “too close to home” sort of experience for us—Charlie is a Roman Catholic layperson and a scholar of religion and theatre, and Justin is a priest in the Anglican tradition and a theologian. Conspiracy in religious garb (and cowls!) fuels The Mysterious Mother’s Oedipal engine, with mastermind Benedict and his sycophant-sidekick Martin using the age-old tools of guilt, shame, and doubt to manipulate the Countess of Narbonne and her family in grotesque and shocking ways that make for extraordinarily fun parts to play.

The anti-Catholicism of Walpole is in full force here, clearly, to which we were both sensitive as scholars and practitioners of high church traditions. It became a welcome challenge to balance these monks’ almost campy plotting (delicious scenes of secretive meetings and villainous monologues inviting the audience to hiss or delight at their evil genius) and the seriousness of their misdeeds.

For Justin, playing so obvious an exemplar of clerical vice was something of a cautionary tale, the vulnerabilities and risks of pastoral power put on display here in a way more vivid than even the most brilliant page of Foucault. And certainly, in the wake of the clerical sex abuse crisis, all religious leaders could use more attention to the ways that spiritual authority can go horrifically awry.

For Charlie, the play’s refusal to distinguish between sacred, political, academic, and theatrical power circulated through our concrete lecture hall turned gothic churchy-stage.

This production represented a conscious confrontation between interwoven identities and historical consequences. We walked to the sound of familiar Latin chants; we adopted postures and gestures we learned through our ordinary ritual practices. To embody these characters endorsed this play’s relevance to both historical and contemporary interpretations of religion but also illuminated shifting cultural attitudes toward Walpole’s “obscenity” and Christianity’s meanings.

For all that, The Mysterious Mother has a great deal in common with the religious tradition it so roundly chastises, namely its obsession with the supernatural, the miraculous and the providential—whether in the guise of mysterious weather patterns (lightning-blasted monuments!) or tragic necessity. In the end, Walpole dramatizes something much more interesting simply than a new atheism-style critique of the immorality and hypocrisy of religious belief: the cracks and fissures in modernity’s supposedly areligious veneer, the return of the repressed, the tremendous fascination of mystery.