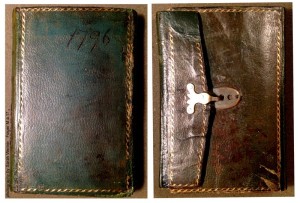

Cover of Jane Porter’s pocket diary. Photograph by Sarah Werner. Folger M.a.17

Julie Park, Assistant Professor of English at Vassar College, describes her fascinating recent research into the “written documents of daily life from real eighteenth-century lives” at the Folger Shakespeare Library:

It’s been a critical commonplace after Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel to view the novel as the first literary form to represent psychological individuality in the context of everyday life. My research, however, examines how the spaces and objects of daily life in eighteenth-century England worked as vehicles of interior experiences in their own right. Working from this angle might change our conceptions of the novel, not only its historical relationship to how selfhood is defined, but also its relationship to the material culture of the greater society around it.

By using my Folger long-term fellowship to look at written documents of daily life from real eighteenth-century lives, I thought I might complicate claims about the early novel’s method of representing interior or psychological experience through diurnal structures.1 One line of my exploration was how a form of portable interiority surfaced in the small books that were designed for carrying in one’s pocket. The novel itself, in its eighteenth-century print manifestation, was pocket-sized, conveying not only its affordability and portability, but also its ability to be held in the hand and worn against the body. Just as the novel conveyed its own interior worlds to readers, the experience of reading the physical book created an interior world between the novel and its reader, even when carried into exterior settings, from pleasure gardens to carriages for travel.2

Among the holdings of eighteenth-century pocket-sized books I found at the Folger is The Ladies Memorandum Book, for the Year 1796 (M.a.17), a green leather book with gold tooling around its edges. At 12×7.5 cm, it can easily be held in the palm of one’s hand. Its fore-edge is covered by a flap that extends from the front cover and is attached to the back by a gold clasp. Flipped to its back, with its diagonal seamed flap, the book resembles a modern day envelope. Yet its sides are left open, and there is a thickness to its body created by the stack of pages sewn into its spine. Further examination of the book will reveal it indeed functions as much of an envelope and a pocket as a book.

Read the rest of Julie Park’s account of this object at the Folger’s blog.