This essay is republished with permission from Nursing Clio, where it first appeared.

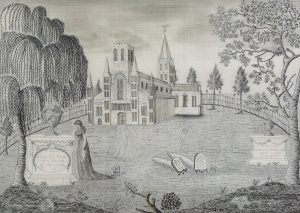

An 1805 needlework mourning picture with two embroidered inscriptions that read: “In Memory / of / Henry Ten Eyck / obit 1st July 1794 / AEt: 8 Yrs & 5 Mths” and “In Memory of / Catharine Ten Eyck / Obit:25th. Aug: 1797 / AEt: 18 Months.” (Margaret Ten Eyck/Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library)

My Story

When I found out I was pregnant on July 1, 2016, I thought it was the beginning of a story to which I knew the ending. My partner, Carter, and I had only just decided to try to become pregnant. It was our first attempt, and it was a success! What a wonderful, happy story. One month later, several of our close friends and most family knew our news. But when we went for our first ultrasound on August 5, we were devastated. There was no heartbeat. The technician went to get the doctor, who told us how common miscarriages were and how many times he gave this bad news in a day. I learned that what I had experienced was a missed miscarriage—the pregnancy had ended, probably around week 6 or 7, the heart had failed to beat, but my body hadn’t reacted. I held myself together until we left the building, and then the loss overwhelmed me. I wept uncontrollably in the car and started messaging all of our friends and family. “There is no heartbeat, I lost the pregnancy.”

More than anything, I felt how I had lost a story of the future that I had built up in my mind. We had been discussing names, thinking about how to arrange our lives around a baby. About what it would be like to have a child, a family together. What has followed in the last two years has been even more difficult than I could have imagined and has required many alterations to our pregnancy story. The loss of the expected narrative and the discovery of new narratives is what I want to focus on here.

When I lost my pregnancy, I started to feel like everything else in my life was also “miscarrying,” especially my work. I’m a professor of eighteenth-century literature, and I was about to go up for tenure in the year following my loss. I had to prepare a summary of my work for the university to review, and I felt like a failure: I focused on rejections and questioned my productivity. But over the course of the past two years (and, I should say, with the help of psychotherapy) I have started to revise that narrative and to become more confident. I also began to see pregnancy and child loss in the literature I study and love, and this discovery led to acts of commemoration for me.

Mourning Pregnancy and Infant Loss in the Eighteenth Century

My experiences with pregnancy, loss, and infertility have made me think about how similar losses would have felt in the eighteenth century. Britain’s Queen Anne (1665-1714) had seventeen pregnancies, only three of which resulted in live births [1]. Anne’s biographer, Anne Somerset, notes that even though “inconsolable sorrow could be condemned as impious or even sinful, it proved difficult for Anne to endure her tribulations with fortitude” [2]. The idea that too much grief was unchristian was common in the eighteenth century, and women were often blamed not only for the impact they might have on their fetus but also for excessive grieving after the loss of a pregnancy or child [3].

Nicole Garret has noted the tendency for male advice writers to downplay child loss and “impose a rationale of consolation” on women [4]. But women weren’t so easily convinced. Lady Frances Norton “spent years stitching original poetry about her dead daughter upon covers, stools, and chairs”[5]. Women also wrote poetry to their unborn fetuses that focused on “the burden of pregnancy and the fear of injury to either the mother or to the foetus” [6]. Mothers who left their children at London’s Foundling Hospital also left textile tokens sometimes personalized with embroidery. The token was meant to help identify the child if the mother could later come back and claim them [7].

One fictional scene of maternal grief inspired my own research and became therapeutic for me [8]. In her 1814 novel, The Wanderer, Frances Burney describes a scene reminiscent of those reproduced in embroidered mourning pieces of the era. The heroine of the novel, Juliet, and her friend Gabriella stand over the grave of Gabriella’s young son. They are in a “church-yard upon [a] hill” and with a “full view of the wide spreading ocean” when Juliet sees her friend “bend over a small elevation of earth,” and Juliet responds by “leaning over a monument” while she bathes herself in tears at the grief of her friend [9]. Before Gabriella recognizes Juliet, she assumes she is a fellow-mourner and asks: “Alas, Madam! are you, also, deploring the loss of a child?” The two grieve together so earnestly “that neither of them seemed to have any sensation left of self, from excess of solicitude for the other” [10].

My embroidered mourning piece based on Frances Burney’s The Wanderer (1814). (Alicia Kerfoot/Nursing Clio)

After reading this scene and looking at surviving examples of mourning pictures, I began my own embroidered mourning picture. I wanted to make material not only my grief but also my research. I sketched an interpretation of the scene from The Wanderer and included the traditional elements of a mourning piece. When I’m finished, I’ll write the names of the family members I’ve lost over the past two years on the tombstones. I’ll also write “angel child” on one of the tombstones, which is what Gabriella calls her son. The mourning picture often depicted national or communal grief and was meant as an exercise in needlework for young women; it especially flourished in America after the death of George Washington [11]. In this scene from The Wanderer and in the embroidered mourning pieces of the era, the public or communal fuse with the personal. One example from the Winterthur Museum (the headline image of this article) includes inscriptions to two children: one aged 8 years and one aged 18 months.

My embroidery is a memorial to my lost pregnancy and a work of hope that the narrative will change soon. When I embroider, I can control the stitches and the appearance of my work; I can see it progress, stitch-by-stitch, and it gives me satisfaction. Bridget Long notes that in the eighteenth century, “needlework acted as a distraction while women pondered personal concerns” [12]. It has certainly worked that way for me.

My personal copy of a first Canadian edition of Anne’s House of Dreams (1917). (Alicia Kerfoot/Nursing Clio)

Another Queen Anne: Infant Loss in L. M. Montgomery’s Anne’s House of Dreams

Anne’s House of Dreams does the same kind of commemorative work as a mourning piece. In August 1914, the same week that WWI began, L. M. Montgomery lost her infant, Hugh Alexander, at birth. Montgomery was in the middle of writing Anne of the Island (1914) and dedicated herself to finishing the novel, despite “a lethargic depression.” She wrote: “never did I write a book under greater stress” [13].

Anne’s House of Dreams, which was published in 1917, was the novel that materialized this grief. In the novel, Anne and Gilbert settle into their “house of dreams” on Prince Edward Island. The book focuses on Anne’s friendship with her neighbor, Leslie Moore. Leslie is trapped in an unhappy and difficult marriage and often envies Anne’s happiness. When Anne tells her she is pregnant with her first child, Leslie responds “so you are to have that, too,” though later she stitches “a tiny white dress of exquisite workmanship” with “delicate embroidery” as a show of her love [14]. When Anne’s baby, a girl named Joyce, dies shortly after birth, she is dressed “in the beautiful dress Leslie had made” [15].

In the novel, Anne downplays her talent as a writer, saying, “Oh, I do little things for children. I haven’t done much since I was married. And I have no designs on a great Canadian novel . . . that is quite beyond me” [16]. Sarah Emsley connects this attitude to how Montgomery’s work was being classified as children’s literature at the time, even though Montgomery didn’t imagine it to be so [17]. In response to a letter from a reader who “thought her characters were unrealistic” Montgomery wrote, “Do you think Anne was happy when her baby died—when her sons went to the war—when one was killed?” [18]. She linked the death of Anne’s baby to losses she would experience during the war, and all in response to a suggestion that Montgomery’s own writing was idealistic rather than serious.

I think that in Anne’s House of Dreams Montgomery aligned Anne’s lost infant with the lost voices of woman writers. That her first child is a girl who dies at birth, and her second is a healthy boy of “ten pounds,” seems to parallel the way that Anne hands over the writing of the “great Canadian novel” to Owen Ford, a male journalist from Toronto. What Anne does end up writing is a new narrative that imagines what Joy would have looked like if she had lived: “she would have been over a year old. She would have been toddling around on her tiny feet and lisping a few words. I can see her so plainly” [19]. She keeps Joy alive in her mind and writes a narrative for her. It isn’t the one she expected, but it’s one in which Joy gets to have a voice, “lisping a few words.”

New Narratives

Though L. M. Montgomery experienced the loss of an infant, some of what she had Anne give voice to resonates with my experience of pregnancy loss and infertility. So many times these past two years, I have thought about what might have been and what might be. I have connected my own struggles to write with my inability to become pregnant. And now I have been thinking about a new narrative: that of being the parent of a child conceived with a donor egg. I think about the community of women stitching together, mourning together, and writing new narratives of loss and hope together in the fiction that I love, and it makes me grateful for what I’ve experienced. It has been difficult, but it’s given me empathy and made me attend to the losses of those around me.

Carter and I have also been overwhelmed by how many people have shared their stories with us. Not long after my miscarriage, a friend started a blog on the complexity of pregnancy loss. More recently, I was moved by a post by Sophie Coulombeau on the devastating but so common story of such losses. Friends, family, and acquaintances have offered support. It is thanks to their generosity that we can afford the donor egg process and are ready to begin it, but how this part of the story will end, I have no idea.

Notes

- Anne Somerset. Queen Anne: The Politics of Passion. New York: Vintage Books, 2012. 81, 162.

- Somerset. Queen Anne. 75.

- Jenifer Buckley. Gender, Pregnancy and Power in Eighteenth-Century Literature: The Maternal Imagination. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. 192.

- Nicole Garret. “Mansplaining Maternal Grief” (paper presented at American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Annual Meeting, Orlando, March 2018). 2.

- Garret. “Mansplaining Maternal Grief.” 4.

- Buckley. Gender, Pregnancy, and Power. 191.

- John Styles. Threads of Feeling: The London Foundling Hospital’s Textile Tokens, 1740-1770. London: The Foundling Museum, 2013. 13, 57.

- I also gave papers on the subject of this scene at the meetings of the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism, the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, and the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies in 2017 and 2018.

- Frances Burney. The Wanderer; or, Female Difficulties. 1814. Eds. Margaret Anne Doody, Robert L. Mack, and Peter Sabor. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. 385-386.

- Burney. The Wanderer. 387.

- Rozsika Parker. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. London: I. B. Tauris, 1984. 136. Anita Schorsch. “Mourning Art: A Neoclassical Reflection in America.” The American Art Journal 8.1 (1976): 5.

- Bridget Long. “‘Regular Progressive Work Occupies My Mind Best’: Needlework as a Source of Entertainment, Consolation and Reflection” Textile 14.2. 182.

- Quoted in Mary Rubio, Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Anchor Canada, 2010. 185.

- L. M. Montgomery. Anne’s House of Dreams. 1917. Toronto: Seal Books, McClelland-Bantam, Inc. 105.

- Montgomery. Anne’s House of Dreams. 117.

- Montgomery. Anne’s House of Dreams. 138.

- Rubio. Lucy Maud Montgomery. 289.

- Quoted in Rubio. Lucy Maud Montgomery. 426.

- Montgomery. Anne’s House of Dreams. 192.