Dear Sir, if my unnotic’d name,

Not yet proclaim’d by trump of fame,

Has reach’d your lugs, then swith attend,

This essay of a Bard unkend.

–Turnbull, “Epistle to a Black-smith” (1788)

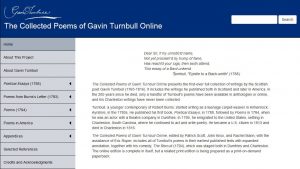

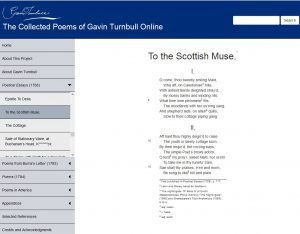

The Scottish poet Gavin Turnbull (1765-1816), a younger contemporary of Robert Burns, published two books of poetry in Scotland before emigrating to America in 1795, where he contributed poetry to South Carolina newspapers. The Collected Poems of Gavin Turnbull presents the first-ever full collection of Turnbull’s writings.

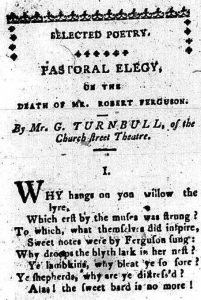

Turnbull, born in the Scottish Borders, started writing poetry as a teenage carpet-weaver in Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, in the 1780s. He published his first book, Poetical Essays, in 1788, followed by Poems in 1794, when he was an actor with a theatre company in Dumfries. In 1795, he emigrated to the United States, settling in Charleston, South Carolina, where he continued to act and write poetry, publishing not only in Charleston but also in the prestigious Philadelphia magazine Port Folio. He became a U.S. citizen in 1813 and died in Charleston in 1816. While he twice issued proposals for a new collection of his writings, and a further invitation to subscribers was published after his death, no collection ever appeared. Only a handful of his earlier poems have been available in anthologies or online, and his Charleston poems have never previously been collected.

The Collected Poems of Gavin Turnbull contains 89 individual poems and songs, organized according to the date of their first publication. The poems are grouped into one of four sections, following the sequence of the books, manuscript, or periodicals in which they are first found. Turnbull’s two prose prefaces to the poetry (1788, 1794) and his short play The Recruit (also 1794) are included, but placed last, after the poems, as appendices. A list of the individual poems and songs in each section and links to the texts are available in the gray drop-down menu on the left-hand side of the screen. With the few exceptions noted below, this edition only includes each poem once, under the date of its first appearance, and poems that Turnbull subsequently reprinted are not repeated in the later section(s).

The Collected Poems of Gavin Turnbull contains 89 individual poems and songs, organized according to the date of their first publication. The poems are grouped into one of four sections, following the sequence of the books, manuscript, or periodicals in which they are first found. Turnbull’s two prose prefaces to the poetry (1788, 1794) and his short play The Recruit (also 1794) are included, but placed last, after the poems, as appendices. A list of the individual poems and songs in each section and links to the texts are available in the gray drop-down menu on the left-hand side of the screen. With the few exceptions noted below, this edition only includes each poem once, under the date of its first appearance, and poems that Turnbull subsequently reprinted are not repeated in the later section(s).

This edition aims to reproduce Turnbull’s texts as they were encountered by their first readers. The text used is therefore taken from the first published version, and where a poem was printed two or more times, the earliest text is used, though any substantive differences between early and later texts are fully noted. The one exception to this general policy is for Turnbull’s poem “The Cottage,” first published in 1788 with four stanzas, for which the edition uses Turnbull’s expanded version with a fifth, more political stanza, from the 1794 collection, also subsequently reprinted in a Charleston newspaper.

The first section contains 50 poems and songs, all probably written while he was still living in Kilmarnock, and published in Turnbull’s first book, Poetical Essays (1788), published by subscription and appearing with the imprint of a Glasgow bookseller. The next short section prints three of Turnbull’s songs which Robert Burns forwarded in a manuscript letter by Robert Burns to George Thomson (October 29, 1793) for possible inclusion in Thomson’s Select Collection of Original Scottish Songs. The second major section contains the twelve poems or songs that were first published in Turnbull’s second volume, Poems, printed in Dumfries in 1794. As noted above, Turnbull’s play, The Recruit, which had been included in the 1794 volume, is placed separately with the “Appendices.”

After he emigrated to Charleston, South Carolina, Turnbull’s contributions to local newspapers included reprinting some earlier poems, as well as newly-written items. The third major section of the edition contains twenty-five poems, ranging in date from 1796 to 1809. Of the twenty-five, twenty-one are items that Turnbull had never previously published; the four reprinted items are the four songs that Turnbull himself extracted from his play The Recruit for separate newspaper publication, and which are therefore given similar separate status here. Though he also wrote an ode to General Washington, both in the theatre, where he appeared in such Scottish plays as Ramsay’s The Gentle Shepherd and Home’s Douglas, and in the poetry he published, Turnbull continued after emigration to identify himself as a Scot.

The online edition of The Collected Poems of Gavin Turnbull allows for fuller annotation than will be provided in the planned print edition, especially in glossing words that might cause difficulties for students outside of Scotland, as well as linking to related material, such as contemporary images and music, where Turnbull often specifies the tune to which he has written new song-text. The first note on each text records its publication history, both first publication and any reprinting in Turnbull’s lifetime. The first note may also contain general background information relevant to the poem. Subsequent notes linked to specific lines gloss difficult or distinctive words, suggest literary sources or allusions, and provide historical or background information. Turnbull’s own footnotes to some of the poems, in Poetical Essays (1788) and Poems (1794), have been included but are placed in square brackets, and introduced as “GT’s note,” to differentiate them from the editors’ notes. The annotations are numbered sequentially rather than by line number and can be accessed in one of two ways. The user can move the cursor over a superscript number in the body of the text, so that a dialogue box will appear with the annotation alongside the line it is explaining, or the user can scroll down the poem and find the relevant numbered annotation where the notes are grouped together in sequence at the end of the text.

The online edition of The Collected Poems of Gavin Turnbull allows for fuller annotation than will be provided in the planned print edition, especially in glossing words that might cause difficulties for students outside of Scotland, as well as linking to related material, such as contemporary images and music, where Turnbull often specifies the tune to which he has written new song-text. The first note on each text records its publication history, both first publication and any reprinting in Turnbull’s lifetime. The first note may also contain general background information relevant to the poem. Subsequent notes linked to specific lines gloss difficult or distinctive words, suggest literary sources or allusions, and provide historical or background information. Turnbull’s own footnotes to some of the poems, in Poetical Essays (1788) and Poems (1794), have been included but are placed in square brackets, and introduced as “GT’s note,” to differentiate them from the editors’ notes. The annotations are numbered sequentially rather than by line number and can be accessed in one of two ways. The user can move the cursor over a superscript number in the body of the text, so that a dialogue box will appear with the annotation alongside the line it is explaining, or the user can scroll down the poem and find the relevant numbered annotation where the notes are grouped together in sequence at the end of the text.

The texts and annotation are supplemented by Patrick Scott’s introductory essay on Turnbull’s life and writings and by a reference bibliography. All text files have been marked-up and prepared in accordance with TEI P5 guidelines—the standard XML language in the humanities—to allow for greater interoperability, both in this edition and future projects. Work on the edition was supported by an ASPIRE grant from the Vice-President for Research, University of South Carolina. The online edition is complete in itself, but Patrick Scott’s selection, A Bard Unkend: Selected Poems in the Scottish Dialect by Gavin Turnbull (Scottish Poetry Reprints no. 10, 2015), is also available, as a print-on-demand paperback and on-line, and a parallel print edition is under consideration.

The texts and annotation are supplemented by Patrick Scott’s introductory essay on Turnbull’s life and writings and by a reference bibliography. All text files have been marked-up and prepared in accordance with TEI P5 guidelines—the standard XML language in the humanities—to allow for greater interoperability, both in this edition and future projects. Work on the edition was supported by an ASPIRE grant from the Vice-President for Research, University of South Carolina. The online edition is complete in itself, but Patrick Scott’s selection, A Bard Unkend: Selected Poems in the Scottish Dialect by Gavin Turnbull (Scottish Poetry Reprints no. 10, 2015), is also available, as a print-on-demand paperback and on-line, and a parallel print edition is under consideration.

Sheffield: Print, Protest and Poetry, 1790-1810

Sheffield: Print, Protest and Poetry, 1790-1810