Like many of you, I’ve followed the V21 developments with much interest and excitement, if I’ve largely done so from the margins (this is the first time I’ve been a part of any formal discussion about V21). There are so many things to commend and discuss about the manifesto and the published symposia, roundtable discussions, and essays that are out in the world now (particularly V21’s visions for institutional critique, which I hope we can talk more about in our discussion but which I’m actually not going to talk about now); what I do want to talk about is V21’s call for “strategic presentism” and how it relates to my vantage point in 18th-century studies. The term itself, which of course recalls Gayatri Spivak’s “strategic essentialism,” is, as I understand it, an attempt to retrieve presentism from the charge of anachronistic projection (a reading of the present uncritically into the past and a collapsing of historical identity and difference) and to redeploy it as a way to signal how the past informs the present, is at work in the present, and how the present shapes itself according to this examined past. While this sounds all well and good, I have to admit that, as I have been trying to follow the V21 collective’s adventures, I just keep getting stuck here at this concept (stuck as in stunned or perplexed). Is this really a problem for 18th-century studies? Do we need a strategic presentism to signal the urgency and relevancy of our field?

Like many of you, I’ve followed the V21 developments with much interest and excitement, if I’ve largely done so from the margins (this is the first time I’ve been a part of any formal discussion about V21). There are so many things to commend and discuss about the manifesto and the published symposia, roundtable discussions, and essays that are out in the world now (particularly V21’s visions for institutional critique, which I hope we can talk more about in our discussion but which I’m actually not going to talk about now); what I do want to talk about is V21’s call for “strategic presentism” and how it relates to my vantage point in 18th-century studies. The term itself, which of course recalls Gayatri Spivak’s “strategic essentialism,” is, as I understand it, an attempt to retrieve presentism from the charge of anachronistic projection (a reading of the present uncritically into the past and a collapsing of historical identity and difference) and to redeploy it as a way to signal how the past informs the present, is at work in the present, and how the present shapes itself according to this examined past. While this sounds all well and good, I have to admit that, as I have been trying to follow the V21 collective’s adventures, I just keep getting stuck here at this concept (stuck as in stunned or perplexed). Is this really a problem for 18th-century studies? Do we need a strategic presentism to signal the urgency and relevancy of our field?

I think my stuckness has everything to do with where I am situated in the broader field—race, empire, and slavery studies. I can’t really speak for the whole of 18th-century studies (although I’d like to have conversations about this whole today), but the field of slavery studies is shot through with strategic presentism. I think this concept (and the need for it) was puzzling to me, because it’s something so obvious in slavery studies. Race, empire, and slavery have a certain almost irrefutable significance in the present. I mean, not only does it instantly signal a special kind of monstrousness if one doesn’t understand the present import of studying the history and representations of race, empire, and slavery, but also these things have such clear, obvious, well-articulated afterlives in the present that seem redundant to even mention (which I could mention, but the point is that I don’t have to). And 18th-century scholars of slavery are really adept at making these strategically presentist moves in their research, teaching, discussions, works in progress, etc. Just in the two race, empire, and slavery panels I went to yesterday, for instance, (one on Ramesh Mallipeddi’s Spectacular Suffering: Witnessing Slavery in the 18th-century British Atlantic and one on “Life and Death in and across Race and Empire”) the following issues were raised: how the form and logics of 18th-century abolition continues to affect our thinking today (the upshot: we’re stuck in abolitionist paradigms, help … we need new paradigms!), the untapped potential for 18th-century philosophers of moral sentiment (Hume, Smith, etc.) as models for deploying sentiment as crisis management and for creating a vocabulary and paradigm to deal with what certain bad historical actors are doing to harm fellow humans (and how to stop them), the continuities of the relationship between 18th-century discourses of displacement (one example being restoration rewritings of The Aeneid) and the current Mediterranean migration crisis (Charlotte Sussman’s talk), and Swift’s Laputa in Gulliver’s Travels and drone warfare (Peter DeGabriele’s talk). This morning’s roundtable on presentism (“Mind ‘Yore’ Business? Eighteenth-Century Studies and the Problem of Presentism”) offered up even more examples: Al Coppola’s paper on the persistence of Newtonian enlightenment assumptions in the present, specifically how our blind faith in universal laws undergirds popular scientific studies like Geoffrey West’s Scale, and Grace Rexroth’s paper on 18th-century typography, neuroscience, and MRI memory studies. And I could go on…

If anything, there’s too much presentism in race, empire, and slavery studies. What we risk is not just misreading the texts of our past and what they can offer us in our present but a misapprehension of the present as well (more on this in a minute). I don’t think the answer is a return to reductionist historicist paradigms (those that V21, I think, are usefully critiquing) but a dialectical presentism, a presentism that can hold the past and present at once, that can account for an interdependence of identity and difference, that can project a future out of this mess and tangle of conjunction and disjunction. This need for but also demonstration of such a dialectical presentism came up for me in one of these aforementioned panels from yesterday when Suvir Kaul made a comment about how he thinks the Black Lives Matters Movement is influencing his teaching of the 18th-century. The example he gave was of a student in one of his courses who was essentially waiting all semester to get to Equiano’s Narrative, only to express profound disappointment once there and declaring it accommodationist, not seeing it as a narrative of self-making as he was hoping she would. Now, as we were discussing at the panel, to some degree the Narrative is accommodationist, but it’s also self-making and non-accommodationist, but we perhaps see only the former and have this kind of disillusioned feeling and reaction because we’re expecting Equiano to belong to a certain black community that exists today (our imagination of this kind of continuity of black collectivity is the thing Stephen Best critiques in his 2012 essay “On Failing to Make the Past Present,” which we also discussed). Such a need for dialectical presentism also comes up in my own work, which is, among other things, about what the study of servitude and slavery (and its relationship) can tell us about the present, in particular what it can tell us about the history of race as a concept—that race is an ideological concept that we made and that we have representations of its making, which, of course, means that it can be unmade. But in order for it (and racism) to be unraveled in the present, we have to recognize that it wasn’t always like this, that race was not a settled, congealed category in the worlds of (especially early) 18th-century texts. Distance and difference are necessary in our present in order to understand the past, the present itself, and to work for a different kind of future. So, presentism is a problem, and I think that, if we are to use it strategically, then it must be a dialectical one, so why not call it that?

One question that Katarzyna Bartoszynska and Eugenia Zuroski asked in their call for this roundtable is whether or not the 18th century offers different approaches to the problems V21 so deftly lays out. In some respects, I think that’s what I’m trying to get at. Perhaps the 18th century is uniquely situated as a field to see the need for some form of dialectical presentism. As I see it, our period is one of emergence, a period that showcases the simultaneous identity and difference of a host of now intelligible modern categories (and ones that are perhaps more settled in the 19th century), whether we’re talking about race, the novel, the author, the nation, the bourgeois subject, or sexuality, etc. The 18th century is strategically positioned to show us how things are made (and how they can be unmade) if we can figure out how to let it, and I think its transitional character gives us a useful model for understanding the dialectical relationship between our present and our past as we try to work for new futures.

For the 2018 American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ASECS) conference program, Katarzyna Bartoszynska and Eugenia Zuroski chaired a roundtable responding to the V21 Collective’s intervention in nineteenth-century studies and the possibilities it presented for reflecting on current problems and critical approaches in eighteenth-century studies. Additional contributions to the roundtable can be found here.

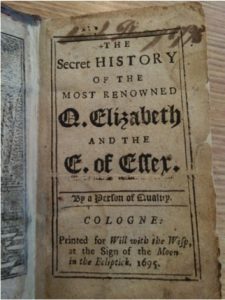

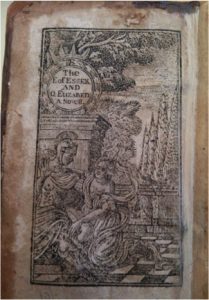

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs.

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs. Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.

Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.