As a Jane Austen scholar, I get to go to some pretty incredible libraries—The Huntington Library in San Marino, California, The Morgan Library in New York City, The British Library in London, the Chawton House Library at Jane Austen’s “Great House” in Chawton among them. But an amazing library with Austen riches in Beverly Hills? Yes, believe it or not, there is one. I spent several happy days there researching for my book, The Making of Jane Austen (2017). The glamour quotient of that trip might seem lower to you, however, when you learn that I arrived via city bus.

It was a pretty great bus ride, all in all. The bus inches along Sunset Boulevard (yes, that Sunset Boulevard) to a stop at Vine (and yes, that Vine!), passing Chateau Marmont and some seriously upscale shopping. I felt pretty much the opposite of the beautiful people, carrying an enormous computer bag, wearing a dowdy sweater, and facing the prospect of spending several sunny California days entirely indoors. For a library rat, it’s absolutely worth it.

The Margaret Herrick Library, also known as the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, or the Oscars Library, holds countess papers and files that document Jane Austen’s afterlife in Hollywood. I made an appointment to see their unpublished materials on the making of MGM’s Pride and Prejudice (1940), that much loved or hated (and sometimes both loved and hated!) film starring Greer Garson as Elizabeth Bennet and Laurence Olivier as Mr. Darcy. I knew from the online catalog that the library held production files, publicity photographs, and many scripts, but I had little idea what was in them. Only a handful of scholars had ever described this material. Even those few treated these materials rather briefly. I figured that even if it turned out to be a lot of junk, I could describe that. I needed to see it all for myself, in order to cover the stage-performance-turned-into-early-film part of Austen’s afterlife.

Arriving at the Herrick Library turns out to be a rather grand event. The place may look like a church, but it’s locked down like a bank. I had my identity checked by the security guard, stowed most of my possessions in a locker, noticed the familiar names engraved on the walls, walked up the staircase, checked in with the librarian, and found a desk. Then I got my first look at the files. I started with the glossy, black-and-white publicity stills for Pride and Prejudice taken by MGM. There were hundreds of gorgeous shots. Unfortunately, researchers aren’t allowed to take their own photographs of anything at the Herrick, even for personal research purposes. The library also has a strict policy on the small number of paid photocopies a researcher is allowed per year. This is a big scholar-bummer, but knowing those constraints made me focus differently. These images are still seared into my memory, because it seemed my only option.

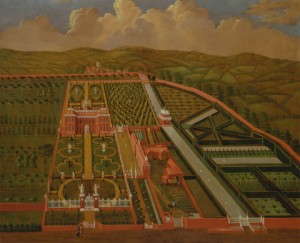

The shots of the set were stunning. To see them up close made me reimagine the amount of expense and care that went into designing details large and small, from the walls to the furniture to the props. The photographs of the cast wearing those oh-so-wrong Victorian costumes were also riveting, even if they are cringe-worthy examples of historical research gone wrong. It was clear from the production files that the costumers thought that lumping together fashions from 1810s, 1820s, 1830s or even the 1840s couldn’t make all that much difference. (One wonders how any Hollywood costume designer thinking through the amount of fashion change that was seen from through 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s could possibly think so.)

What I remember best from the production photographs, however, are the casual shots taken on set during filming. There was an arresting photograph of Judy Garland “stopping by” oh-so-casually—and coincidentally with a photographer on hand!—to visit Garson in her Pride and Prejudice dressing room. Another photo shows Garson reading an enormous nineteenth-century volume—a book prop—between takes, as she sits on a director’s chair near the set’s unintentionally hilarious “Rare Books” storefront. I suppose one could argue all books were rare in the eighteenth century, when buying even one volume was something out of the reach of most regular people, but “rare books” was not yet a commercial term.

A photograph of the outdoor table from the film’s famous archery scene between Elizabeth and Darcy shows that someone had delicately taped over a naked putto’s nether regions. A casual photo of Garson in costume as Elizabeth, getting an archery lesson from a man in a white undershirt, was terribly funny in its sartorial and historical contrast. A shot of Olivier and Garson in costume, receiving dance instruction from a modern-dress husband-wife team, was similarly amusing but at the same time surprisingly moving. A dedication to the study of movement—for teachers and students—was well captured in this photo.

Another shot of two men, Olivier, dressed as Darcy, and the film’s director, Robert “Pop” Leonard, in his Colonel Sanders-like outfit, playing badminton together in between outdoor takes was priceless. A shot of the English members of the cast, in a down moment, enjoying a tea break, seemed both staged and true-to-life. It made visible the trans-Atlantic elements of the production very clearly, too.

But the best photo of all is one of the Bennet sisters posed at the edge of the set. The five actors are standing together, in a costumed line, in front of doors with signs above them. The doors presumably lead to a women’s dressing room. The largest sign reads, “Thru These Portals Pass the Most Beautiful Girls in Meryton,” with smaller letters below that warn, “Positively No Admission,” and “The Little Girls Club.” There is also an obscured notice that seems to advertise an on-set knitting club.

The photos definitely whetted my appetite to learn more about the making of this film, but it was the typescript files that turned out to be an absolute feast. I moved from the production stills to the print files. I knew the rough outlines of the agonizingly slow play-to-film journey of MGM’s Pride and Prejudice, which had its start in Helen Jerome’s 1935 Broadway hit play and was rewritten by a series of screenwriters for Hollywood. It’s a story that has been told many times before, and I won’t repeat that five-year odyssey here, except to say that it involved not only predictable casting changes but a premature and unexpected death. (If you want to learn about why the story of Harpo Marx’s role in it all is greatly exaggerated, you’ll have to check out my book.)

What I got to read in those Herrick Library script files were drafts that few have had a chance to digest before. There were dozens of Pride and Prejudice screenplays—“failed” scripts–with Austen-inspired scenes and dialogue never brought to life. Some of these scripts were truly dreadful. It was all I could do to stifle my laughter as I read these preposterous scenarios, from the full-on mud-splashings proposed for Elizabeth and Darcy (two different versions had each of them successively doused in mud) to the heart-of-gold neighborhood gypsy named Tony. Obviously, though, laughing out loud would not have been okay, as sounds of any kind are frowned upon in libraries in general. The Herrick especially inspires silence and awe, with its spotless, white Bob Hope Lobby and its elegant, olive-green Katharine Hepburn Reading Room. I tried to limit myself to broad smirks. Believe me, it was a challenge.

You can read more of the gory details of these ridiculous failed scripts in my book’s chapter seven, but I can’t resist sharing one more tidbit. In one early version of the screenplay, Mr. Darcy, Mr. Bingley, and Colonel Fitzwilliam go off on a crazy bachelor weekend to London. In one of their misadventures, they end up wagering on a dog versus monkey fight. Colonel Fitzwilliam bets on the monkey, but Darcy’s money is on the dog. And it turns out that that bit, at least, was vaguely historically accurate! There was a fighting monkey, Jacco Macacco, that fought in the Westminster Pit in London and was made famous by Pierce Egan in his Life in London (1821). It’s the book that gave rise to the characters Tom and Jerry, so it’s especially amusing to think of Darcy, Bingley, and the Colonel as precursor bro-friends transposed into those roles. Whether you’re a fan of the 1940 Pride and Prejudice or not, the final version of the film will rise in your estimation once you realize just how much worse things might have been.

I also came away from reading these scripts doing more than laughing. Reading them makes one realize how these screenwriters were really in a tough place. They were trying to find—they were no doubt being charged to create—ways to make Austen seem fresh to millions of late 1930s moviegoers who may never have heard of her or who knew of her only glancingly. Screenwriters were throwing whatever they could think of at Pride and Prejudice, including the conventions of Westerns and screwball comedies. In the end, I thought, we should probably be more generous in assessing their attempts, even if you feel, as I do, quite relieved that most of these ideas never saw the screen.

I came away from the library thinking, “Long live Jane Austen in popular culture, whether in Beverly Hills or London or Chawton—whether in enough mud for a full-body wrestling match or with just a few glorious inches of it worn around the ankles—and whether you are cheering for the dog or the monkey.”

P. S. The Herrick Library was very generous with me during my visit, providing access to a lot of material and invaluable research assistance. I’m especially grateful to librarian Jenny Romero, who helped me find just the right things to read. I’m also thankful to the staff there, who never raised their eyebrows too high, even if an audible laugh or two may have escaped from me unawares.

You can read more about The Making of Jane Austen, watch a book trailer, see additional images, and order your own copy at makingjaneasten.com.