When Cynthia Roman, Curator of Prints at the Lewis Walpole Library asked me if I would be willing to stage Horace Walpole’s 1768 The Mysterious Mother as part of the year’s “Walpolooza” events, I hesitated at first. Like Walpole himself, who “did not think it would do for the stage,” I nonetheless realized that I too “wish to see it acted” [1]. For those who are not familiar with the play, the story opens with Edmund, Count of Narbonne, returning to his ancestral home from the crusades with his friend and fellow soldier Florian. Edmund was banished by his mother, presumably because he arranged to sleep with a lady’s maid, Beatrice, the night after his father’s death. Edmund has had no contact with his mother for sixteen years, though she has sent him money from the estate she has inherited (a breach of patrilineal protocol motivated by her late husband in his love for her). Edmund assumes that she is being manipulated by the priest of the adjacent abbey, Father Benedict, and his protégé Father Martin, but on his return, he finds her defiant, refusing to confess, yet tormented. She is convinced she has hallucinated her husband’s ghost when she first sees him. Edmund, stunned by his mother’s majestic demeanor in the midst of her distress, nonetheless hopes for a reconciliation through his newfound love for her young ward, Adeliza. The Countess misunderstands the proposed union, thinking that Florian loves Adeliza. Father Benedict begins to connect the guilty dots, seizes the moment for his vengeful triumph over the Countess, and hastily marries Adeliza to Edmund who, when they come to seek the Countess’s blessing, instead drive her to the horrified confession that Benedict has been trying to extract for years: that her sexual longing for her husband, who unexpectedly died before he could return to her bed, drove her to disguise herself as the maid her son Edmund was to sleep with that night and put herself in his bed. Edmund is unaware of the bedtrick, but the Countess knowingly has sex with her son. They conceive Adeliza and launch a lifetime of alienation and guilt. When the secret finally explodes in the revelation of a now-double incest plot, the Countess commits suicide with a dagger. Edmund, shattered, vows to return to the wars while Adeliza retreats to a convent.

When Cynthia Roman, Curator of Prints at the Lewis Walpole Library asked me if I would be willing to stage Horace Walpole’s 1768 The Mysterious Mother as part of the year’s “Walpolooza” events, I hesitated at first. Like Walpole himself, who “did not think it would do for the stage,” I nonetheless realized that I too “wish to see it acted” [1]. For those who are not familiar with the play, the story opens with Edmund, Count of Narbonne, returning to his ancestral home from the crusades with his friend and fellow soldier Florian. Edmund was banished by his mother, presumably because he arranged to sleep with a lady’s maid, Beatrice, the night after his father’s death. Edmund has had no contact with his mother for sixteen years, though she has sent him money from the estate she has inherited (a breach of patrilineal protocol motivated by her late husband in his love for her). Edmund assumes that she is being manipulated by the priest of the adjacent abbey, Father Benedict, and his protégé Father Martin, but on his return, he finds her defiant, refusing to confess, yet tormented. She is convinced she has hallucinated her husband’s ghost when she first sees him. Edmund, stunned by his mother’s majestic demeanor in the midst of her distress, nonetheless hopes for a reconciliation through his newfound love for her young ward, Adeliza. The Countess misunderstands the proposed union, thinking that Florian loves Adeliza. Father Benedict begins to connect the guilty dots, seizes the moment for his vengeful triumph over the Countess, and hastily marries Adeliza to Edmund who, when they come to seek the Countess’s blessing, instead drive her to the horrified confession that Benedict has been trying to extract for years: that her sexual longing for her husband, who unexpectedly died before he could return to her bed, drove her to disguise herself as the maid her son Edmund was to sleep with that night and put herself in his bed. Edmund is unaware of the bedtrick, but the Countess knowingly has sex with her son. They conceive Adeliza and launch a lifetime of alienation and guilt. When the secret finally explodes in the revelation of a now-double incest plot, the Countess commits suicide with a dagger. Edmund, shattered, vows to return to the wars while Adeliza retreats to a convent.

Walpole had declared it “delicious entertainment for the closet,” but our task was to bring it out of the closet. The Mysterious Mother’s incestuous “secret sins” led both Walpole and friends to claim it was too “disgusting,” too “dreadful,” and altogether too much for the London stage. Yet Walpole made surreptitious efforts to stage it and printed multiple editions [2]. Private readings, including one organized by Frances Burney at court while she was Keeper of the Robes for Queen Charlotte, introduced small audiences to its “dreadful” charms, and the Rev. William Mason’s commentary angled for a stage-ready version, in which the Countess’s crime would become accidental so that she could deserve pity and forgiveness, in true Aristotelian fashion. Walpole rejected these suggestions as undermining his main point, the Countess’s deliberate decision and the weight of her ensuing guilt. Burney and Coleridge both proclaimed their disgust with play and playwright after reading it, but Burney’s Edwy and Elgiva owes something to it, while a less squeamish Shelley, inspired by Walpole, dove headlong into the gothic-incest nexus with The Cenci. My ambivalence about this tantalizing offer mirrored the ambivalence of the author and early readers: is this something that could be done in public? Was this, as Walpole feared, “a tragedy that can never appear on any stage?” Reader, we did it.

Hypertheatricality on a Budget

As George Haggerty has noted in Queer Gothic, stage tech after Walpole became more hypertheatrical, especially in Lewis’s The Castle Spectre. We tried to produce the hypertheatricality the play evokes and helped to usher in using digital projections and animations. With the help of Alice Trent’s design, we unfolded Walpole’s tale in the valley between a shadowy gothic castle and a monastery, as fog rolled, thunder rumbled, and crows cawed. The 55-minute production, with all tech run out of Keynote, included 26 discrete animated slides with sound cues. The soundscape began with Ola Gjeilo’s 2012 “Ubi Caritas,” an homage to medieval choral textures. Other sound cues included short pieces of Gregorian chant, favoring those performed by Benedictine nuns and monks. The Countess entered to a child singing “Ave Maria.” A Greek orthodox boy’s choir layered over droning became our “chorus of orphans,” with their ghostly outlines floating in the foreground. A clap of thunder erupted from a dark screen, underscoring the Countess’s unraveling as the action transitioned to a garden with a blasted monument in act III. A final thunderclap and a screen that flickered against rain, then faded to black, closed the play. It was campy, dark, and effective.

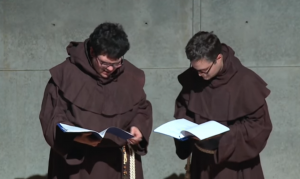

This production was an elaborate staged reading, many months in the preparation but with less than three days to work together in person. The embodiment of the play was always, therefore, an “as if” proposition. To realized what we could of a production, we used the simplest of blocking that allowed actors to navigate the space with certainty while holding scripts in hand. We played in the Yale Center for British Art’s lecture hall, with its raked auditorium seating, a 33 x 16 stage, and fixed lighting. The auditorium’s side stairs allowed the actors to enter to the final strains of “Ubi Caritas.” We used the arc created by a fixed overhead spot to establish the playing area. The corners of the space were comparatively dark and served as retreats or hiding spaces for eavesdropping characters. The edge of the lit area formed a circumnavigational path for the tormented Countess. The monastics used it as well, adding serpentine, labyrinth-like patterns as they disgorged their plots to secure the Countess’s confession. With no back stage or wings, the cast took seats on the front row corresponding to the spaces of the castle and the monastery.

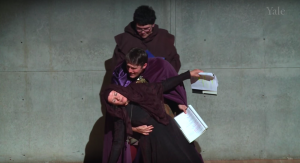

The final scene of The Mysterious Mother

Though the staging was fairly simplistic, there was nothing low-budget about the space and the costumes. The rich costumes, rented from various theatre companies in the area, were nearly fully realized versions of Lady Diana Beauclerk’s drawings, which lent the production a grandeur and gorgeousness beyond the scale of a staged reading. Their gilded details shone in the stark light and clean grey lines of the signature Louis Kahn concrete walls of the Center for British Art. Those walls played a leading role in the production and were forced into the part of visual straight man to the irreverent, haunting, yet campy production. Onto their smooth surface we projected a ruined castle among cliffs and roiling fog, then a ruined monument. Turning Kahn’s high modernism into grey castle walls felt wicked, and we contemplated the architect spinning in his grave as the projector forced the concrete monument to modernism to bear the image of the ruin and the emotional chaos of the fall of the house of Narbonne.

Incest, Camp, and Queerness

As I told the cast early on in our abbreviated process, the only way out of such a play is over the top. The deliberate shock, the “too horrid” subject of incest made the first players at the first private theatrical version of the play giddy. We came to sympathize with George Montagu’s house full of “schoolboys” (George Osborn, John Burgoyne, Capt. George Boscawen), who gleefully read and memorized parts of The Mysterious Mother in 1769. Jill Campbell has observed that Walpole’s use of incest in particular in both The Mysterious Mother and The Castle of Otranto is the displaced sign of queer desire. In our 21st-century performance, the play’s queerness energized moments of campy, panto over-iteration and exaggeration. The campiness of the gothic, with its exaggeration of horror, the in-joke of its material bed-trick, and its queerness avant la letter came out in our initial laughter, our campy gestural exaggerations, and the embodiment of the perverse passion at the center of the story. The young men strutted, Adeliza melted, and the priests gleefully rubbed their hands together in a pantomime of villainy. We ran the risk of laughter, our own and the audiences, while trying to use exaggeration to find the horror of the situation. It is was both fitting and an additional gift from the universe that of the rented costumes, Florian’s (Gilberto Saenz’s), had been made for a young Nathan Lane.

Asking a Blessing

Nunning Up

In order to make the play performable in an hour, David Worrall had removed most of the theological and discursive monologues, but the presence of religious debates over agency, will, and guilt haunted our cut. The Countess’s refusal to submit to Catholic authority, in the form of her would-be confessor Benedict, defines the action of the play. Set in Narbonne, France, with its unfinished gothic cathedral, at some point immediately after the Reformation, the play is as much about the Reformation as it is about incest. The Countess’s majestic outline and her genuine psychological torment, which she refuses to mediate or absolve through religious confession, make her modern. She is Walpole’s attempt to “exhibit a character whose sincere penance was not degraded by superstitious bigotry,” a walking trope of defiance to clerical authority that also forced her to bear her own sins. Georgina Lock, in her widow’s weeds and with regal bearing, gave us a Countess who could defy Benedict but then implode under the weight of her guilt, folding in from the solar plexus, from the womb, as she contemplated the horror of her situation. Her majesty, wilting into near collapse, was the gestic signature of the erotic and religious crisis at hand. She dislocates guilt from a religious to a secular realm and bears her own sins. As a woman who refused to be sexually passive or religiously compliant with the Mother Church at the dawn of the Reformation, she defies the terms of both gender and piety in favor of a modernity that embodies the tension between spiritual and secular accounts of the human condition.

The nunnery and the abbey are familiar locations for transgressive figures. Convent porn is almost a cliché in the eighteenth century, with the monastery, especially after the Mad Monks of Medmenham, close behind. George Haggerty has more thoroughly mapped out the connection between “the heteronormativity of sexual violence and the patriarchal law of the father on which Catholicism depends” that leaves sexuality and religion “inextricably bound” in the English cultural imagination [3]. Knowledge becomes carnal knowledge; secret sins are both religious defiance and sexual perversity. Having two Yale Divinity graduates, one an Episcopal priest (the Rev. Justin Crisp) and the other a Roman Catholic theologian and performance studies scholar (Charles Gillespie) playing the evil priest-tormenters added a delicious frisson for those in the know, but they also brought their own reflections on Reformation history and the concept of confession to the performance. The Iago-like incommensurability of Gillespie’s Benedict and his determination to extract the Countess’s confession and to claim her as a confessing Catholic is fueled by the contest between a passing orthodox and an emerging secular age. Benedict’s fight for her soul and his parting words, “Who was the prophet now? Remember me!” signify for him the triumph of Papal authority over her defiance. Outside the circuit of heterosexuality, he finds a way to inseminate from the space of the seminary by other means. What Stuart Curran has noted of The Cenci applies to The Mysterious Mother: “the paternal power in this play is almost mystical, a direct reflection of God’s authority and the Pope’s. A daughter’s rebellion, like an angel’s, opens an intolerable breach in the fixed hierarchy of nature, which tyranny or no, must be maintained” [4]. Walpole revels in the rupture, glorifying it in the Countess’s regal bearing and steadfast refusal to submit to the authority of the church, yet he also finds himself architecturally enthralled by the Catholic church and thematically drawn to themes of guilt, sin, and transgressions that will out.

Notes

- Horace Walpole to Montagu, April 15, 1768, Correspondence, 10.259.

-

Mason to Horace Walpole, May 8, 1769, Correspondence, 28.9.

-

George Haggerty, Queer Gothic (Chicago: U Illinois P, 2006), 64.

-

Stuart Curran, Shelley’s Cenci: Scorpions Ringed with Fire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970), 67.