Lake Eola (2005) by Steven Willis

In March of 2018 I attended the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies conference in Orlando, Florida and delivered a brief paper on John Evelyn’s late-seventeenth-century pamphlet Fumifugium: Or, The Inconvenience of the Aer and Smoake of London Dissipated. The panel’s topic was “Intimations of the Anthropocene/Capitalocene,” and it was scheduled on the conference’s final day and in its final time band, which seemed fittingly apocalyptic given that we were all talking environmental cataclysm. What follows is a reconceptualization of that paper based on insights from the other panelists as well as dialogue with the audience:

I am afraid I won’t have much that is meaningful to say about our unspeakably vexed environmental present—our “-cene,” be it “Anthropocene,” “Capitalocene,” or some other—except to stress its continuities to the past. Obviously, the broiling present of our hotbox planet cannot be ignored, and nor can the climate refugees who are its victims. But I am not yet convinced that there is anything actionable that eighteenth-century studies can say to those whom environmental degradation immiserates except “a lot of people in a lot of places and times saw this coming.” Even so, the bottom-out environmental condition of “major system collapse after major system collapse after major system collapse,” as Donna Haraway puts it, must niggle at the consciences of those of us who drove to that conference with our sacred gasoline just as it must have weighed on the minds of those of us who flew there on the strength of aviation turbine fuel—a signal petro-chemical achievement in combustibility [1]. Even the Orlando International Airport, that great gateway to the Disney phantasmagoria, must drag down our ecologically privileged souls: twenty square miles of concrete poured out over a drained swamp where airport employees likely fire propane cannons to scare birds lest their flights disturb ours.

Fumifugium (1661) by John Evelyn

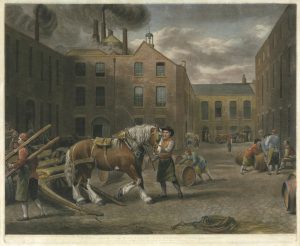

To come back to Evelyn, his Fumifugium is quite simply an anti-air pollution pamphlet. It was published in 1661 and then later reproduced several times in the eighteenth century, notably in 1772 by antiquarian Samuel Pegge the elder. In the document proper, Evelyn outlines and Pegge reiterates a geo-engineering project in two strokes: first the removal of certain industries from the pleasant—read upper class—urban places they are polluting, followed by the mass planting of fine smelling trees. “But the Remedy which I would propose,” Evelyn writes, “require[s] only the Removal of such Trades, as are manifest Nuisances to the City, which I would have placed at farther distances [from the city]; especially, such as in their works and Fournaces use great quantities of Sea-Coale, the sole and only cause of those prodigious Clouds of Smoake” [2]. A simple and economically productive way to carve out a refuge: move all the burning industries six miles south of London, for who knows what rabble lives and can be poisoned there. The title of this post—“Heavy fumes of charcoal creep into the brain”—is W. H. D. Rouse’s English translation of the Latin epigraph on Fumifugium’s title page [3]. The epigraph itself comes from Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura, a famed example of the consolation of philosophy. I won’t gloss De Rerum Natura here, but the intertext is important [4]. In an atomistic universe, one in which the collision of primary particles determines events and happenings, the material residues of fire and smoke are essential. Smoke’s waftings alter things in the human world—they alter the body and brain as Evelyn points out. Smoke is the clinamen of atoms in perhaps its most obvious form—a classic example of the “airborne toxic event” that we all face down for the remainder of our days [5]. This is how Evelyn’s tract describes London’s repellent air pollution. The unavoidable smoke and its “black and smutty Atomes […] insinuate[s] itself into our very secret Cabinets, and most precious Repositories,” both bodily and architectural [6]. “It enters by several branches into the very Parenchyma, and substance of the Lungs […] together with those multiform and curious Muscles, […] which becoming rough and drye, can neither be contracted, or dilated […]” [7]. According to Evelyn, the noxious burning of coal can be laid at the hands of “Brewers, Dyers, Soap-boilers and Lime-burners,” whose pursuits unquestionably endanger all.

A View from the East-End of the Brewery Chiswell Street (1792) by George Garrard

“[I]t is manifest,” Evelyn writes, “those who repair to London, no sooner enter into it, but they find a universal alteration in their Bodies, which are either dryed up or enflamed, the humours being exasperated and made apt to putrifie, their sensories and perspiration so exceedingly stopped, with the losse of Appetite, and a kind of general stupefaction, succeeded with such Catharrs and Distillations, as do never, or very rarely quit them, without some further Symptoms of dangerous Inconveniency so long as they abide in the place […]” [8]. Moreover, and because of the use of coal, the trees can no longer bear fruit, flowers no longer flower. People are condemned to the “strange stupidity” of being “fumo praefocari,” that is, “suffocated by smoke.” It is stunning that Evelyn’s understanding of the bodily effects of anthropogenic air pollution anticipates our own so neatly. And so what is to be done to remediate these dangers? On the one hand, “fumifugium” can mean “removal of smoke.” According to this translation, the “constant and unremitting poison” of “smoake” can actively be eliminated, or “dissipated,” by human ingenuity and labor, both of which create value. I’d like to gesture to an alternate construal of “fumifugium” as “flight from smoke.” For me, this slant translation both anticipates the dire predicament of our own moment’s evaporating refugia and, conversely, gets to the heart of the inhuman dream of imperial capitalism from the seventeenth century to today: whether by flights of industrious fancy or fleets of frigates, the Earth always offers a new territory lucratively to destroy [9]. At least, that is, until it doesn’t. Evelyn is an environmentalist type who is legible in our own ruined moment. Even as he condemns the “sordid and accursed Avarice of some few particular persons” whose means of being produce the inescapable London smoke that Evelyn finds so “impure” and “uliginous”—a word that I learned means “slimy” and “miasmic”—Evelyn’s condemnation is also actually a statement of his own worth as projector. When Evelyn describes what others have done to make London the “Court of Vulcan” and—one of my favorite of his metaphors—the “Suburbs of Hell,” he does so in order to announce his own value as improvement thinker, one who will lead the king and (some of) his people toward a more wholesome future by way of industrial displacement and tree planting. These are labor-producing endeavors, the green jobs of long ago.

John Evelyn (1689) by Godfrey Kneller

Fumifugium is an originary biopolitical text. Its arguments are grounded in the fact, attested by eighteenth-century Bills of Mortality, that air pollution was a public health disaster even as it was caused by economic activities meant to keep the population alive and growing. Evelyn writes: “The Consequences then of all this is, that (as was said) almost one half of them who perish in London, dye of Phthisical and Pulmonic distempers.” Smoke is killing children, which in any economy qualifies as biopolitical quandary. Secondly, the Fumifugium is a prophetic text in its way. Evelyn’s distaste for fire—that originary human experience of capitalism, log after log, coal after coal, without end—derives in part because fire threatens to ignite the city, as it would five years later in the Great Fire of London. Perhaps most interesting for readers of The 18th-Century Common is the Fumifugium’s afterlife. Samuel Pegge’s 1772 edition all at once dissociates the text from its Restoration context and repurposes it for the new polluting industries of the Georgian era. One hundred years after the 1661 publication, nothing and everything was different. “We may observe how much the evil is increased since the time this Treatise was written,” Pegge writes in the preface to the 1772 edition. Industrial pollution has not abated but increased, a queer thought to think from 2018 looking at 1772 looking at 1661. Regarding the term “Anthropocene,” the Invisible Committee writes, “At the apex of his insanity, Man has even proclaimed himself a ‘geological force,’ going so far as to give the name of his species to a phase of the life of the planet: he’s taken to speaking of an ‘anthropocene.’ For the last time, he assigns himself the main role, even if it’s to accuse himself of having trashed everything—the seas, and the skies, the ground and what’s underground—even if it’s to confess his guilt for the unprecedented extinction of plant and animal species” [10]. For these authors, our hubristic term “Anthropocene” is more of the same: it’s Evelyn in 1661, in 1772, in 2018. “But what’s remarkable,” the committee writes, “is that we continue relating in the same disastrous manner to the disaster produced by our own disastrous relationship with the world” [11]. So how do we rethink this “disastrous relationship,” and, actually, can we?

Notes

[1] Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities. Vol. 6 (2015). 1.

[2] Evelyn, John. Fumifugium: Or, The Inconvenience of the Aer and Smoake of London Dissipated. London: B. White, 1772. 34.

[3] Lucretius. “Carbonumque gravis vis, atque odor insinuator / Quam facile in cerebrum?” De Rerum Natura. Trans. W. H. D. Rouse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1924. 5.803-4.

[4] By “intertext,” I refer to a general connection between two different pieces of writing. In this case, Lucretius’s work clearly influences and animates Evelyn’s project.

[5] In Lucretius, “clinamen,” or swerve, refers to the spontaneous and unpredictable movement of particles that lead to different potentialities. “Airborne toxic event” is a reference to the second part of Don Delillo’s White Noise (1985).

[6] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 20.

[7] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 26.

[8] Evelyn, Fumifugium, 24.

[9] See other articles in this series, including Cynthia Williams’s “Napoleon, an English Poet, and the Gas Lighting of London” and Nick Allred’s “Locke’s American Wasteland.”

[10] The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends. Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e) (2014). 32.

[11] The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends, 32.