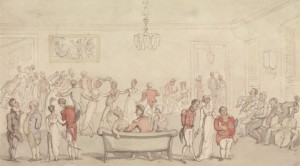

Elegant Company Dancing (undated). Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827, British). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

One of the great pleasures of Austen’s fiction derives from her relentless focus on social conduct. All of Pride and Prejudice’s characters, with the possible exception of thoughtless Lydia, are self-conscious about their own and judgmental of the behavior others. As such, Austen has been long recognized as a brilliant observer of sociation, small group interaction, and the rules of conversation. In her capacious understanding of not just the hows of behavior in public places, but the whys of behavior in public spaces, Austen prefigures the development of micro-sociology, those analyses of specific rituals, such as Georg Simmel’s study of cocktail party talk and flirtation, or Erving Goffman’s later analysis of civil inattention (how not to attract stranger’s attention on the street) or waiting room or elevator behavior. While the connection of Austen’s novels to twentieth-century social science might seem dubious, any reading of her letters shows an active empiricist at work, recording the most minuet details of dress, expression, and conversation in her lab book, drawing quick and witty conclusions for Cassandra about fashion and character.

Reading Austen from a sociological perspective enables us to see more clearly not just the vivid description of social interaction, but her analysis of that action. This distinction between the arbitrary rule and its ethical basis or form is perfectly exemplified in the following paragraph from Mansfield Park, at the visit to Sotherton, which proves to be a perfect playground for all the younger characters to exercise their selfishness. Julia is unhappily left behind with the elders [Aunt Norris and Mrs. Rushworth], while everyone else scatters:

The politeness which she [Julia] had been brought up to practice as a duty made it impossible for her to escape; while the want of that higher species of self-command, that just consideration of others, that knowledge of her own heart, that principle of right, which had not formed any essential part of her education, made her miserable under it.

Julie understands the letter but not the spirit of the law, the outer form but not its object.

Pride & Prejudice is particularly amenable to the interests of Erving Goffman, for he meditates on first impressions in Presentation of Self in Ordinary Life, and more deeply in Stigma, which helps us to understand how Darcy is complicit in his first and terrible impression at the Merytown assembly. Darcy and Elizabeth’s aggressive conversation at the Netherfield Ball demonstrates just about every imaginable violation of polite conversation. And finally, if the first half of the novel charts a series of offences up to Darcy’s disastrous and wounding proposal at the Huntsford parsonage, everything from his exculpatory letter onward is remedial, and follows the essential form of apologies that Goffman lays out in Relations in Public.