“Chinese Pagoda and Bridge, in St James’s Park” (1820) by Edward Wedlake Brayley

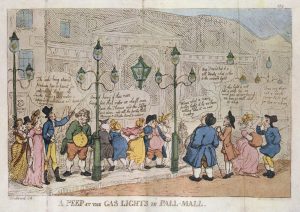

Almost before the ink was dry on the Treaty of Fontainebleau in April of 1814, people of all stations and occupations—including allied generals, monarchs, and heads of state—converged on London to celebrate Napoleon’s defeat with a panoply of special events: processions, dinners, balls, performances, worship services, and much, much more. As Edward Orme reported in his souvenir Historical Memento, especially creative were the uses of light [1]. Illuminations were staged in a wondrous variety of places, from banks and parks to the Houses of Parliament; amid the countless candles, oil lamps, torches, and fireworks blazed the efforts of the Gas Light and Coke Company. This young enterprise had just launched an ambitious and truly transformative infrastructure project: installing gas lights on the streets of London. Seven years earlier, Pall Mall had been the first street anywhere in the world to be lit with gas, and now, with legislation permitting bold and extensive excavation, the company eagerly contracted with the government to participate in the grand celebrations of Napoleon’s exile (Conlin 7) [2, 3]. Undaunted by issues of scale, their pièce de resistance was the Chinese bridge and pagoda erected in St. James Park, which included 10,000 gas flames. Within a year the company had laid thirty miles of gas pipe in the city (Conlin 7) [2]. By 1826, “fifty-three British cities had gas mains,” and the pace picked up from there (Flanders 219) [3]. It’s hard to overestimate the impact of gas lighting on London, “the first city to establish uniform lighting as a civic obligation” (Flanders 219) [3]. After all, as Jonathan Conlin reminds us, lighting was not simply an incidental feature of the public sphere; it actually helped to create the public (13) [2].

Felicia Hemans’s poem “The Illuminated City” (1826) is said to have been inspired by just this coincidence: the celebrations of 1814 and the installation of gas lights in London [4, 5, 6]. Although Hemans’s body of work fell out of favor at the end of the nineteenth century, during her lifetime this enormously popular poet was understood to speak for all of England. As scholar Tricia Lootens has put it, “[f]ew poetic careers can have been more thoroughly devoted to the construction of national identity than was that of Felicia Hemans” (239) [7]. So it’s not surprising to read her poem “The Illuminated City” as referencing the incorporation of gas lighting into a civic celebration that helped recalibrate English identity for a post-war paradigm. While the text does not name London (opting instead for allusion, which is typical of Hemans’s work), the spectacle of the “royal city” evokes a key moment in English national, imperial, and even (we inhabitants of the Anthropocene might say) planetary history.

In a sensory-rich opening stanza, fire blazes from an array of sources. In the hills, hamlets, forests, and especially the city, “festive light” shines from “lamps [. . .] upon tower and tree”; pillars are “wreath’d with fire”; spires resemble “shooting meteor[s]”; silhouetted buildings sparkle in “the clear dark sky.” Through its comprehensive reach, this vista takes in and stabilizes all the varied elements of the landscape; thus, the glow of victory unifies. Soon, however, the poetic speaker realizes that these illuminations might succeed too well. The “bright lamp’s glare” is so “dazzling” that he becomes blinded, and so light itself casts a figurative shadow. As the poem explains, these many forms of light prevent us from apprehending vital truths about the cost of war. Life’s “deep story” can only be encountered in those places beyond the glare of gas lamps and fireworks. A foreshortened line of sight replaces the vista, and we are denied access to scenes that the poet values as true. Elaborated through five stanzas, the play of light and dark insists on the limits of vision. Thus, in the end, Hemans’s poem resists any straightforward reading of brightly lit pageantry the likes of which the summer of 1814 offered. Her rendition of the spectacle suggests an attendant crisis of perception, an intimation of persistent illegibility—blind spots, as it were. Occlusion becomes an important dynamic in her poem of post-war illumination.

Felicia Hemans (1837) by W. E. West

A similar crisis of perception also operates in a second, admittedly minor Hemans poem, “The Curfew Song of England” (1834) [8]. This text memorializes a much earlier iconic moment in English history, when William the Conqueror decreed that all his subjects return home at the sound of the bell and extinguish every light. Here the affront is not the blaze that prevents perception, but instead the prohibition against candle, lamp, rushlight, and most importantly the fire in the hearth. In “The Curfew Song,” the fire doused on the order of a foreign oppressor becomes part of the nation’s cultural inheritance. Here, once again, the effect is to obscure the sight the poet claims to want to illustrate, for the text peremptorily snuffs out several scenes in quick succession. As in “The Illuminated City,” then, the obstructed view is integral to the telling of the national tale. Both texts present moments around which English identity is presumed to cohere, and in both cases, representation is compromised through an important point of tension: artificial light and its control.

“A Peep at the Gas Lights in Pall Mall” (1809) by Thomas Rowlandson

So the centrifugal force in Hemans’s body of work—her thematic interest in emigration and military service, her popularity at the farthest Anglophone reaches—is complemented by this additional dynamic. Illumination and its opposite (extinction) are expressions of power with rather complex implications. In “The Illuminated City,” even with lamps and pillars and spires aflame, the full truth of national life remains obscured. New technologies might well overreach, unintentionally limiting the vision of the poetic speaker. Left unacknowledged are the vulnerabilities of the nation that the blaze is meant to celebrate.

Plate V from A Practical Treatise on Gas-Light (1815) by Fredrick Accum

Susan Wolfson has recently explained that in the work of Lord Byron, the Shelleys, and other Romantics, the “macro-discharge of lightning communicated the bold, risky spirit of the age” (757) [9]. That Promethean spark offered a kind of electrical sublime. In fact, the image was current enough that Byron’s imitator William Sotheby described Napoleon’s first defeat as Britain’s “lightning stroke” (as cited by Wolfson, 760) [9]. Quite differently, in “The Illuminated City,” light is neither natural nor instantaneous. Thus, perhaps it presages a much more sustained and comprehensive gamble. On the occasion of Napoleon’s exile to Elba, when England stood at the verge of its fossil-fueled acceleration, the woman whose “mind [was] national property” reckoned with the promise and failings of the moment [10]. Hemans, who, according to her contemporary Jane Williams, unified readers “in the most distant and alienated colonial settlements and in the old home of the British race” (Wolfson 602) [11], anxiously assessed the implications when bright lights obscure sober reflection—when the spectacle of national belonging overpowers and occludes. In both “The Illuminated City” and “The Curfew Song of England,” describing what cannot be seen certainly poses a compositional challenge for the poet, but how she stage-manages sources of light is far more than an aesthetic concern. In these texts, Englishness is associated with the coercive control of artificial light. The expanding networks of gas evoked by “The Illuminated City” reify a pervasive alienation and displacement that have become ever more symptomatic of the Anthropocene. Speaking of our own day, Jonathan Crary has argued that we in the twenty-first century encounter increasing “institutional intolerance of whatever obscures or prevents an instrumentalized and unending condition of visibility” (5) [12]. It would seem that Felicia Hemans has foreshadowed this state of affairs.

Notes

[1] Orme, Edward. Historical Memento Representing the Different Scenes of Public Rejoicing, which took place the first of August in St. James’s and Hyde Parks, London in Celebration of the Glorious Peace of 1814, and the Centenary of the Accession of the Illustrious House of Brunswick to the Throne of these Kingdoms. London, 1814.

[2] Conlin, Jonathan. “Big City, Bright Lights? Night Spaces in Paris and London, 1660-1820.” La Sociabilité en France et en Grande-Bretagne au Siècle des Lumières: Modèles et Espaces de Sociabilité. Ed. Valerie Capdeville and Eric Francalanza. Editions Le Manuscrit, 2014.

[3] Flanders, Judith. The Making of Home: The 500-Year Story of How Our Houses Became Our Homes. Atlantic, 2014.

[4] Susan Wolfson, for example, makes this connection in her edition of Hemans’s work. See Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Letters, Reception Materials. Princeton UP, 2000. 420.

[5] Gary Kelly associates illuminations in the poem with a different expression of power, when mobs would coerce homeowners to light their windows to show partisan support. See Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Prose, and Letters. Ed. Gary Kelly. Broadview, 2002. 345.

[6] “The Illuminated City” was published first in Monthly Magazine as part of a new series in November 1826 (515).

[7] Lootens, Tricia. “Hemans and Home: Victorianism, Feminine ‘Internal Enemies,’ and the Domestication of National Identity.” PMLA 109.2 (March 1994): 238-253.

[8] Hemans, Felicia. “The Curfew Song of England.” The Poetical Works of Felicia Hemans Complete in One Volume with a Memoir, by Mrs. L. H Sigourney. Phillips and Sampson, 1853. 613-614.

[9] Wolfson, Susan J. “‘This is my Lightning’ or; Sparks in the Air.” SEL 55 (Autumn 2015): 751-786.

[10] Review of The Siege of Valencia by Felicia Hemans. See British Critic and Quarterly Theological Review 20 (July 1823): 53.

[11] Jane Williams wrote an entry on “Felicia Dorothea Hemans” for The Literary Women of England, published in 1862. Wolfson includes extensive passages in her collection (602).

[12] Crary, Jonathan. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. Verso, 2013.