Over the past forty years or so, climate researchers have written of the “human volcano” when discussing air pollution and carbon emissions. As early as the 1970s, industrialized nations were spewing so much soot and ash into the atmosphere that the effects imitated a volcanic eruption. In the early twenty-first century, this phenomenon has intensified with the global increase in coal burning resulting in stratospheric pollution previously only seen from volcanic activity. Here’s the connection scientists are making:

When major volcanic eruptions occur—such as Tambora in 1815, or Krakatoa in 1883, or Mount St. Helens in 1980, or Mount Pinatubo in 1991—huge clouds of sulphur and volcanic ash enter the atmosphere and stratosphere, traveling around the globe and causing air quality issues, crop failures, and global temperature changes. But the eruption ends, and, while volcanoes can cause severe environmental damage, the most common eruptions affect Earth’s ecosystems for only few years. However, unlike an actual volcano, the so-called “human volcano” continues to increase steadily over time. There is no end to the eruption—industrialized nations continue to erupt, slowly and without pause. So, while a volcanic eruption is more catastrophic and destructive in the short term, the human volcano can be more long-lasting, producing what climate scientists call “global warming.” Humans, in other words, have become a geophysical force of nature akin to volcanoes.

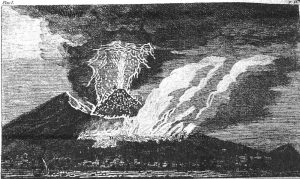

Rob Wood’s depiction of the Tambora eruption in 1815

Humans’ ability to modify Earth’s ecosystems in this manner is a hallmark of the Anthropocene. Literally meaning “The Age of Humans,” the Anthropocene is the proposed name for our current geological epoch, beginning when human activities started to have a noticeable impact on Earth’s geology and ecosystems. Nobel-prize winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen popularized the term in 2000, writing that the Anthropocene refers to “the present, human-dominated, geologic epoch, supplementing the Holocene,” and his writing has spurred nearly two decades of debate among scientists and humanities scholars, with most scholarship centered on defining the characteristics of the Anthropocene and in establishing its dates [1]. Crutzen initially proposed that the Anthropocene began with the Industrial Revolution, citing James Watt’s patent of the steam engine in 1784 as a possible marker, while other scientists have since argued for the “Orbis spike” of 1610 or the “bomb spike” of 1964. The later date has recently emerged as the frontrunner for the dating of the Anthropocene [2].

Photograph of industrial pollution in the twenty-first century

However, the human-volcano effect directs our attention back to the eighteenth century as marking the emergence of the Anthropocene. This human volcano, it turns out, is not unique to our contemporary moment: the practice of comparing human activity to volcanoes is part of a literary tradition that began in Britain in the eighteenth century. Poets, painters, and scientists were fascinated by volcanoes, due in large part to the dual developments of geology and industrialization, as well as the high number of major eruptions during this period, most notably Vesuvius in 1737, 1760, 1767, 1779, and 1794; Laki in 1783; and Tambora in 1815. Eighteenth-century geologists argued that volcanoes played a vital role in the formation and evolution of Earth. The violent eruptions of volcanoes and subsequent processes of erosion, decay, and rejuvenation not only imagined a geological time scale for the first time—that is, “deep time”—but also made volcanoes a major attraction for natural historians and tourists alike. At the same time, a range of authors began using volcanic language and imagery in the earliest depictions of industrialization, which was quickly reshaping the landscape and geography of Britain. This conflation of human and geological phenomena depicts humanity as a geological force in a new geological epoch.

One representative example of the many eighteenth-century poets that fused geological and industrial imagery is the relatively unknown priest and poet John Dalton, who marvels at England’s quickly-changing landscape in his 1755 Descriptive Poem, Addressed to Two Ladies, at their Return from Viewing the Mines near Whitehaven. In the eighteenth century, Whitehaven was a major coal-mining town in northwestern England, and industrial tourism was common at this time—people were obsessed with new industrial technology. In his humorous poem, Dalton depicts the ladies’ tour as a kind of epic-to-the-Underworld narrative, drawing on classical mythology and tropes, but he also supplies real scientific and cultural knowledge about volcanoes and industrialization through a series of extensive footnotes, which were written by his friend, Dr. William Brownrigg. In the poem’s opening stanza, Dalton describes Whitehaven’s coal mines as volcanoes:

Welcome to light, advent’rous pair!

Thrice welcome to the balmy air

From sulphurous damps in caverns deep,*

Where subterranean thunders sleep,

Or, wak’d, with dire Aetnaean sound

Bellow the trembling mountain round,

Till to the frighted realms of day

Thro’ flaming mouths they force their way;

From bursting streams, and burning rocks,**

From nature’s fierce intestine shocks;

From the dark mansions of despair,

Welcome once more to light and air! [3]

Several words and images here reference volcanic eruptions: “sulphuruous damps,” “subterranean thunders,” “Aetnaean sound” (reference to Mount Etna), “trembling mountain,” “flaming mouths,” “burning rocks.” The sights, sounds, smells, and effects of the coal mines parallel those of volcanoes. The footnotes are also quite suggestive. In the first footnote, the author writes of the “dreadful explosions” in the mines, which are “very destructive,” “bursting out of the pits with great impetuosity, like the fiery eruptions from burning mountains” (pp. 1–2). He here refers to natural coal-seam fires, which can burn for thousands of years, but which can also be started by human causes, such as accidents and explosions in mines. In the second footnote, he explains that these unintended fires “burn for ages” (p. 2)—an exaggeration, of course, but one that implicitly links the long, slow progress of a geological age with the experience—and projection—of humans’ imagined geologic imprint.

These volcanic similes and metaphors continue throughout the poem. Dalton references the “perpetual fire” of industry (l. 44), as well as the “hissing,” “moaning,” and “roaring” of the “fire-engines” and other modern inventions, all of which produce substances akin to volcanic lava:

But who in order can relate

What terrors still your steps await?

How issuing from the sulphurous coal

Thick Acherontic rivers roll?* (ll. 87–90)

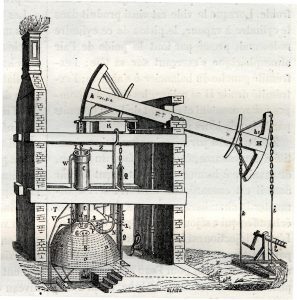

Dalton depicts water pumped from the mines as a kind of hellish water, or lava, akin to the fiery water of Acheron in Hades. In a footnote, he explains the pumping process in more detail, offering a vision of anthropogenic lava: “The water that flows from the coal is collected into one stream, which run towards the fire-engines. This water is yellow and turbid, from a mixture of ocher, and so very corrosive, that it quickly consumes iron” (p. 8).

Newcomen steam pump by Louis Figuer, 1868

Dalton’s Descriptive Poem indicates the trajectory of scientific poetry throughout the eighteenth century. The structure of the poem, which alternates between poetry and extensive scientific footnotes, not only anticipates the style made famous by Erasmus Darwin nearly four decades later but also points toward a confluence of scientific and literary writing on volcanoes and industry. Poets and geologists alike wrote extensively of volcanoes and industrialization, often at the same time. For example, the first English translation of Italian geologist Francesco Serao’s Natural History of Mount Vesuvius was extracted and written about extensively in a 1747 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine and in subsequent issues throughout the 1750s and 1760s. Focused mainly on the 1737 eruption of Vesuvius, this text exemplifies the kinds of descriptions typical in volcano writings, with an emphasis on fire, heat, smoke, clouds, thunder, earthquakes, and a transformation of the surrounding landscape. Significantly, he frequently compares volcanic activity to human effects: he repeatedly refers to underground volcanic fires as “furnaces”; compares volcanic vapors to those in coal mines; and writes, “The Noise of our Vesuvian Thunder was momentaneous, like the Discharge of a Cannon fir’d at Sea” [4].

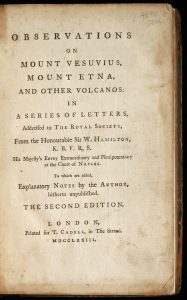

Scientist and explorer Sir William Hamilton also focuses on volcanic-industrial connections in his popular and widely-read Observations on Mount Vesuvius, Mount Etna, and other Volcanos (1773). Like Serao’s text, Observations was extracted and reprinted frequently in literary magazines. At one point, Hamilton compares the smoke and ash of Vesuvius to the fog of London: “it was impossible to judge the situation of Vesuvius, on account of the smoak and ashes, which covered it entirely . . . the sun appearing as through a thick London fog” [5]. As we know now, London’s famous fog was mostly the result of suspended particulate matter: soot, smoke, and dust caused from coal burning. In 1825, Charles Lamb would call this “the ‘London particular,’ so manufactured by Thames, Coal Gas, Smoke, Steam, and Co” [6]. These kinds of scientific-industrial comparisons were widespread in scientific writings: perhaps most famously, the geologist James Hutton presents Earth as a “machine” modeled on the steam engine in his Theory of Earth (1788).

Title page of Hamilton’s Observations

By the early nineteenth century, the volcanic-industrial tradition had become “common place” in British writing, as Lord Byron observes in Don Juan (1824) [7]. Scientists such as Humphry Davy, James Smithson, and Luke Howard began to argue explicitly that industrial emissions had atmospheric effects similar to those of volcanic eruptions. In 1804 the editors of the Edinburgh Review expressed amazement that such a connection had “so long eluded observation” [8]. Howard, writing on London in 1812, referred to the chimneys of the city as a collective “volcano of a hundred thousand mouths” [9]. In 1820, the poet James Woodhouse wrote of the “new volcanoes” in Birmingham and Wolverhampton [10]. This literary trope of referring to the “new volcanoes” of industry continues throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In a 1902 issue of the Illustrated London News, the thousands of chimneys that reach into the sky above Britain’s capital are referred to as “London volcanoes,” and today, climate researchers continue to write of the “human volcano” [11].

Vesuvius Eruption in 1767, Plate 1, Observations

In the twenty-first century, humans have supplanted volcanoes as a major catalyst of climate change. The last five years (2014–2018) were the hottest years on record globally, owing almost entirely to the human-volcano effect. While this warming trend is recent, the connections among industrialization, volcanoes, and climate change are not. These connections, which both signal and describe the Anthropocene, form a tradition in eighteenth-century British writing, pointing to 1750 as the dawn of the Anthropocene.

Notes

[1] Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, “The ‘Anthropocene,’” IGBP Newsletter 41 (2000), p. 17.

[2] For a concise yet comprehensive overview of these debates, see Jeffrey Davies, The Birth of the Anthropocene (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), esp. chapter two. Also see Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, “Defining the Anthropocene,” Nature 519 (2015): 171–80.

[3] John Dalton, A Descriptive Poem, Addressed to Two Ladies, at their Return from Viewing the Mines near Whitehaven (London, 1755), ll. 1–12.

[4] Francesco Serao, The Natural History of Mount Vesuvius (London, 1743), p. 64.

[5] Sir William Hamilton, Observations on Mount Vesuvius, Mount Etna, and other Volcanos (London, 1774), p. 31.

[6] J. C. Thompson, Bibliography of the Writings of Charles and Mary Lamb: A Literary History (London: J.R. Tutin, 1908), p. 88.

[7] Lord Byron, Don Juan, 13.282.

[8] Quoted in G. M. Matthews, “A Volcano’s Voice in Shelley,” ELH 24, no. 3 (1957), p. 197.

[9] Luke Howard, The Climate of London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 203.

[10] James Woodhouse, The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus, in The Life and Poetical Works of James Woodhouse, ed. R. R. Woodhouse (London, 1896), p. 25.

[11] Illustrated London News (15 March 1902), p. 17.

The online edition of

The online edition of  The texts and annotation are supplemented by Patrick Scott’s

The texts and annotation are supplemented by Patrick Scott’s

As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as

As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as  Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.

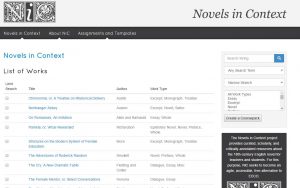

Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.  Novels in Context

Novels in Context