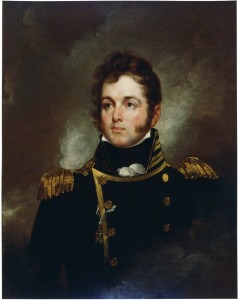

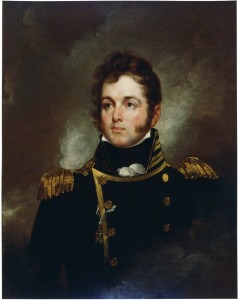

Edward L. Mooney. “The Hero of Lake Erie.” 1839. Portrait in oils after John Wesley Jarvis (1839). U.S. Naval Academy Museum Collection.

The non-Western world was the “common” of 18th-century Europe, territory to be gradually colonized—fenced off, walled off, or hedged off—by powers looking to raise the value (and the rents) of their respective empires. For modern nations forcibly melded and forged within this ruthless cauldron, imperial legacy offers a bitter, but seemingly indispensable path to identity.

In Port of Spain you will find—if lost—a cemetery gate ordained with the British Imperial Coat of Arms, iron corroding from the relentless force of West Indian rains, an eroding misnomer amidst the rising steel towers of the Caribbean’s most dynamic economy. A freshly-placed bronze plaque, a recent gift to Trinidad & Tobago from the U.S. Embassy in honor of the country’s 50th anniversary of independence, denotes its significance.

Here an “illustrious hero and Christian gentleman”—U.S. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry—was once interred following a gracious ceremony by the British governor of Trinidad, Sir Ralph James Woodford. The Commodore succumbed to yellow fever in 1819 on his 34th birthday, but not before becoming a well-known naval hero during America’s first international campaigns—the Barbary Wars and War of 1812. (Commodore Oliver Perry is not to be mistaken with his younger brother, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, the catalyst for prying open Japan to the West in 1853 and the resulting Meiji Restoration. Has a bloodline of American sea-farers ever had a greater impact on history?)

Roncevert Almond. “Perry Gateway at Lapeyrouse Cemetery in Port of Spain, Trinidad.” 2012.

Wandering the streets of Trinidad, I was struck that the true character of a modern nation is not found in the rusting cemetery of empire, but in the living commons—the intellectual and physical space animated by the human spirit. Merely a half-kilometer away, but ages apart, is the birthplace of modern Trinidad & Tobago, Woodford Square. Seated before the country’s Parliament, the Red House, and courts of justice, this public space serves as the beating heart of Port of Spain.

When Dr. Eric Eustace Williams, the nation’s founding father and first prime minister, applied his Oxford education to challenge the British imperial system in Trinidad & Tobago, he did so from Woodford Square. Ever the history professor, Dr. Williams held a series of lectures at the “University of Woodford Square” (as the park became known) that provided the intellectual basis for national sovereignty. Forewarning the struggle of constructing a post-colonial identity, Dr. Williams remarked:

There can be no Mother India, for those whose ancestors came from India. There can be no Mother Africa, for those of African origin. There can be no Mother England and no dual loyalties. There can be no Mother China, even if one could agree as to which China is the Mother; and there can be no Mother Syria and no Mother Lebanon. A nation, like an individual, can have only one Mother. The only Mother we recognize is Mother Trinidad & Tobago, and Mother cannot discriminate between her children. (History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, 1962).

As a result of this political dialogue, Woodford Square was no longer the inert namesake of a former imperial overseer, but a reclaimed center of learning, a breathing manifestation of budding national identity.

Upon the lowering of the Union Jack and the tolling of the Anglican Cathedral’s bells, a new nation was born on August 31, 1962. Addressing the new citizens via radio, the Prime Minister reminded his audience that “democracy means freedom of worship for all and the subordination of the right of any race to the overriding right of the human race.” A contemporary of South Africa’s Nelson Mandela, Dr. Williams laid the pathway to a Rainbow Nation in the Americas. The journey began long ago.

It was on behalf of the Spanish in 1498 that Columbus first spotted the three pinnacles of the Trinity Hills (hence “Trinidad”), but Madrid largely ignored the new colony due to its lack of gold or silver. Lima and Bogota were more enticing jewels during the mercantile economy of the time. Even Sir Walter Raleigh, in search of El Dorado, was disappointed by the lack of spoils and in 1592 sacked the lonely Spanish settlement. In order to populate the island, the Spanish finally resorted in 1783 to issuing land grants to Roman Catholic Frenchmen fleeing pre-revolutionary turmoil at home.

Adam Smith’s industrializing Britain, however, envisioned for its possessions a more complex division of labor. Following Spanish capitulation in 1797, British sugar barons and shipments of African slaves, cogs in the triangle trade of Europe-Africa-America, soon arrived. Amerindian natives were already in steep decline—the exchange of cocoa production for soul salvation from the Catholic Church had resulted in a decidedly one-sided bargain.

In a unique and bemusing act of irony, in 1845 the British began “importing” indentured South Asians to the islands in order to fill the labor shortage at sugar plantations caused by earlier black emancipation. They were supplemented by Chinese, Syrians, and Lebanese workers. The artificial arrival of these “Oriental” exiles, equipped with their Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist upbringing, forced an early debate on multi-racial and multi-religious nation-building.

(Even its current political geography, as a member of the Caribbean states, is more historical accident than natural reality. Trinidad is actually an extension of the Paria Peninsula, an outcrop of the South American continental shelf—as opposed to an independent island arc like the rest of the Lesser Antilles. On a clear day one can spy Venezuela from the capital city; the distance between the countries is only seven miles.)

Consequently, via the formation of Trinidad & Tobago, the journey of Columbus was complete. Europe did not arrive in Asia through the Americas. Instead, the Orient, the tale of Azeri poets and Silk Road travelers, had arrived in the Americas through Europe. On the pleasant banks of this Caribbean island, on the volcanic cliffs of this South American mountain, humankind advanced a peculiar experiment. The West—Indies indeed!

Dr. Williams noted that with independence the people of Trinidad & Tobago faced the “fiercest test in their history—whether they can invest with flesh and blood the bare skeleton of their National Anthem, ‘Here, every creed and race find an equal place.’” (History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, 1962). It is a work in progress, much like the United States.

At the conclusion of my project in Port of Spain, I ventured to Woodford Square and reflected upon the young Commodore, the end of empire, and the continuous journey of a nation. The park remains a lively space for debate and learning. Unsurprisingly, therefore, I came across the latest lesson offered at the University of Woodford Square—an observation on the meaning of “The Age of Obama” and the power of the “changing course of time.” Given the influence of demography upon national identity, as made evident by the U.S. presidential election, it was a fitting stop on the way home.

Roncevert Almond. “University of Woodford Square.” 2012